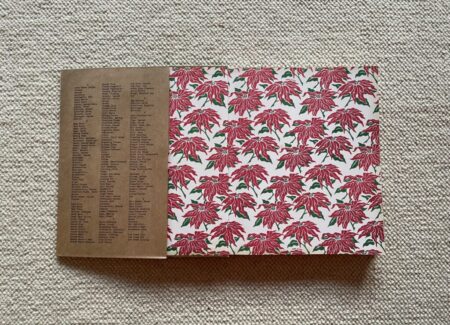

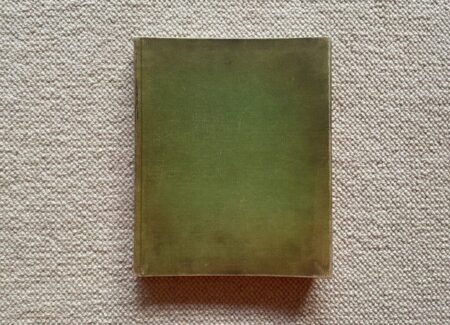

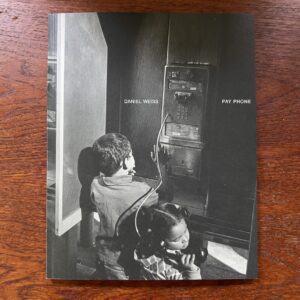

JTF (just the facts): Co-published in 2024 by TBW Books (here) and Éditions Images Vevey (here). Casebound hardcover with French fold dust jacket and printed edges, 9 x 11 inches, 224 pages, with 164 color plates. Includes a plate list. (Cover and spread shots below.)

A special edition of 200 signed, numbered copies of Gong Co. is also available (here). Each book has been altered by the artist to include inserted materials, a tipped-in photographic print, and vintage wrapping paper.

Comments/Context: An edited selection of cover and spread shots has become a common shorthand way to introduce the appearance of a photobook to those who haven’t seen it before. And for the vast majority of photobooks, a representative handful of these kinds of images will adequately document the essence of what it has to offer. But in a few outlier cases, these kinds of standardized pictures fail to communicate what’s actually going on, even though they do accurately reproduce some of the pages.

You may have seen a few spreads or image highlights from Christian Patterson’s recent photobook Gong Co. somewhere on the Internet, as part of a review or maybe even on one of the publisher’s websites, but I’m here to tell you that there is no way that whatever you may have seen (including our own images below) can compare with physically holding this book in your hands and spending time turning its pages. Gong Co. is of course a book of photographs, but as a photobook object, it is unexpectedly immersive and experiential, patiently drawing us into its richly constructed self-contained environment, and it has plenty of complexities to discover and unravel for those who dig in with tenacity. I’m fairly certain that I haven’t seen everything Patterson has embedded in this project, even though I’ve slowly paged through Gong Co. at least a dozen times.

Patterson has been incrementally refining his unique brand of experiential book making for more than a decade now. He burst onto the photo scene with his now-classic 2011 photobook Redheaded Peckerwood, a true crime story delivered in the form of a dossier, filled with photographs, documents, insertions, and other materials and ephemera that collectively told a documentary story that was surprisingly complex and ambiguous; almost single handedly, it re-invented and expanded the vocabulary of layered archival narrative and compilation in photobook form. A few years later (in 2015), he followed that success up with Bottom of the Lake (reviewed here), a personal history of his hometown of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, as seen in a facsimile edition of his family’s local telephone book (circa 1973) as interrupted by countless images, markings, insertions, and other interventions (including audio recordings reached via a phone call.)

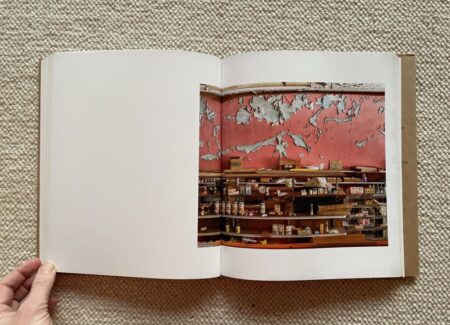

As it turns out, Gong Co. actually got started before either of those other projects, back in 2003, making its gestation period more than two decades long. Its origin story takes us back to Patterson’s early career, when he was living in Memphis and working as an archivist for the William Eggleston Trust. On a car trip down through Mississippi to New Orleans, Patterson stopped in the town of Merigold, and in search of a cold drink, stumbled into what looked like a functioning general store. At that time, Gong Co. was indeed in business, but somehow it had been largely left behind by the modern world, its rickety shelves filled with decades old products. Over the next twenty years, Patterson visited the store now and then, watching it continue to decline and decay, the time warp continuing to trap the place in amber until it eventually closed (in 2013) and the building was demolished (in 2019). Gong Co. documents the arc of that single small town store, as seen primarily through photographs Patterson made there.

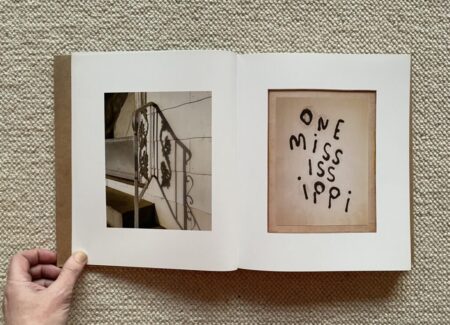

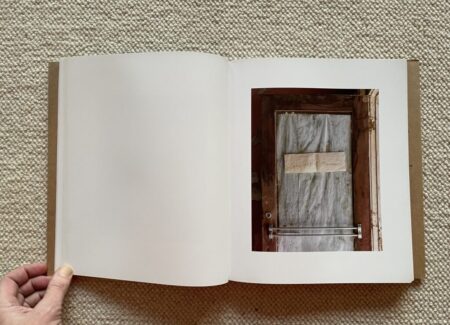

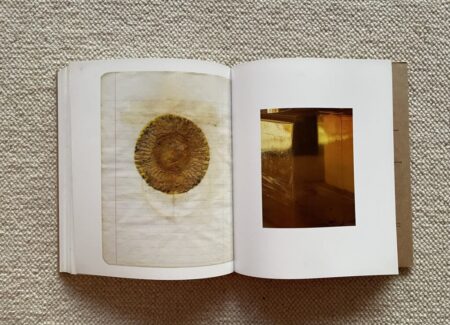

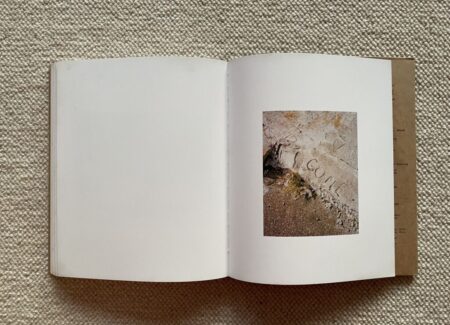

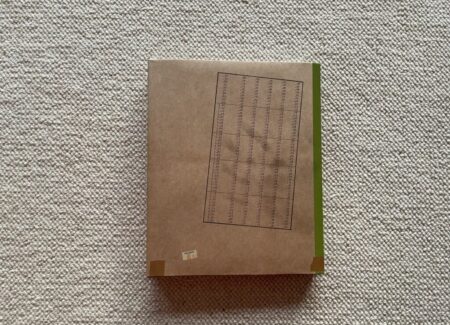

Given Patterson’s sophisticated arsenal of accumulated techniques for incorporating various kinds of materials into his photobooks, it isn’t entirely surprising that Gong Co. employs some of the same methods to further its storytelling. The halftone cover image of the exterior of the store is printed on brown craft paper, the kind used for grocery bags; the cover is folded and wrapped in this paper in the way I remember we used to wrap school textbooks when I was a kid, with printed “tape” holding the edges and flaps together. The back cover features a sales tax calculation chart, a grimy handprint (we’ll get back to that hand in a minute), and a replica price sticker, with the inside flaps of the jacket offering a comprehensive list of the things on offer at the store. The book itself is bound in replica green cloth, with the appearance of fading and wear around the edges, with mold spots and foxing on the fore edge and sides of the pages; the end papers are printed in a dated red floral pattern, again with greasy yellowing along the edges. As much as is likely possible, Gong Co. looks and feels like something old and well used, even though it isn’t.

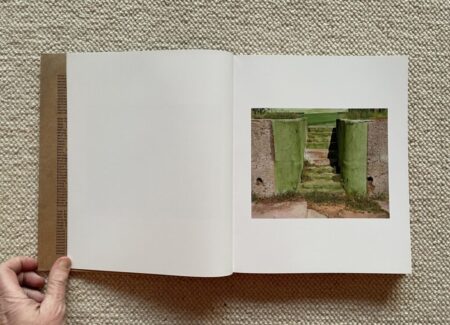

Photographically, Gong Co. begins with a two image invitation of sorts – a place to sit down (in the form of a metal folding chair) and a red ribbon bow to unwrap (on the page with the artist’s name). Patterson then builds out a geographically telescoping journey, which ultimately also moves forward in time. Starting with the cotton fields along Mississippi Highway 61, he introduces us to the town of Merigold, makes images along the streets there, and then discovers the Gong Co. storefront. From there, he ventures inside, making images of the main store area, followed by the office, the storeroom, and the home where the owners lived. The narrative then speeds through time, in a going, going, gone kind of progression, with the store transformed into an empty lot. The book ends with a vintage snapshot of the store in its heyday, and a return to the folding chair where we were sitting, now adorned with two electric candles lit like a mournful shrine.

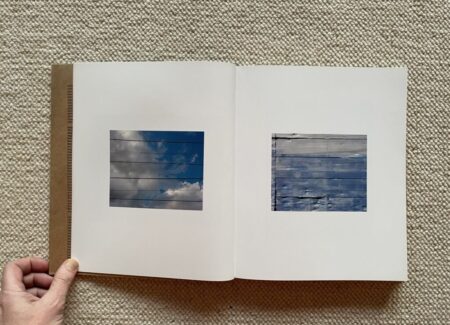

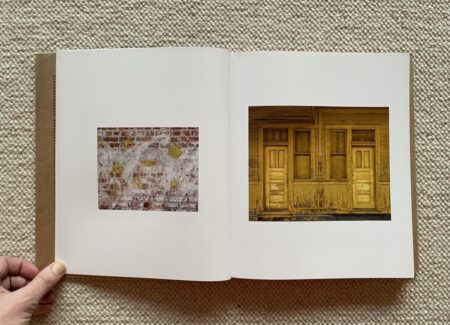

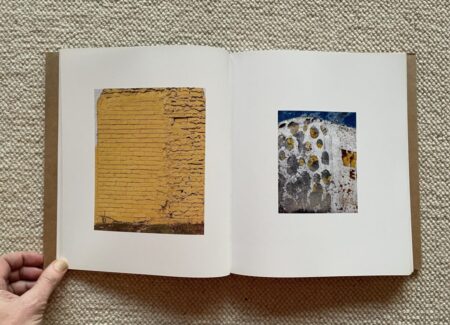

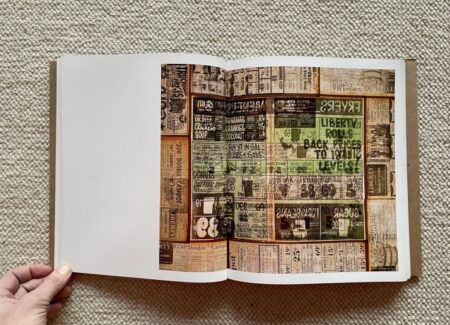

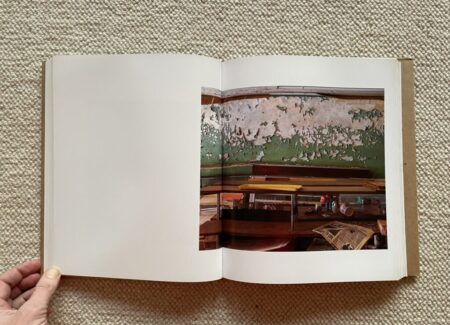

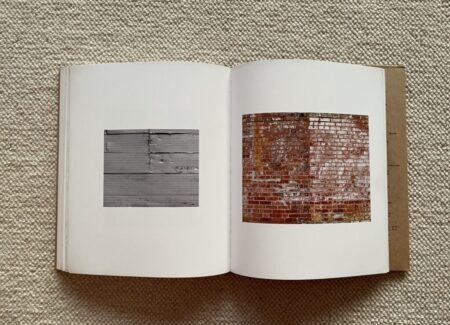

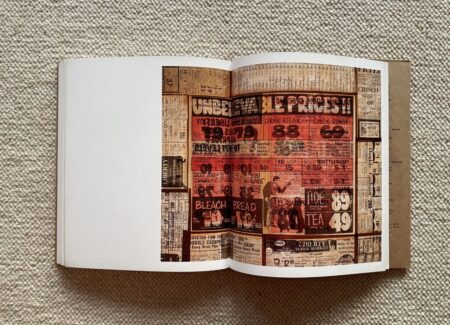

Surfaces provide Patterson’s gateway into this project, with painted stairs, tin siding, fading brick murals, yellow-washed doorways, and boarded up storefront windows offering neatly flattened compositional possibilities. Painted walls, tactile latticework, shadows on the sidewalk, and densely printed grocery store supplements pasted on windows bring along more ordered patterns, but once we walk through the wooden screen door into Gong Co., that kind of formal structuring starts to drift away, mostly due to the chaotic messiness of the interior.

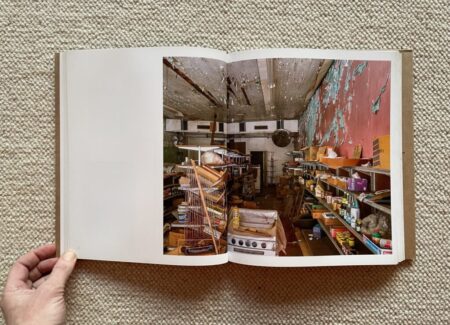

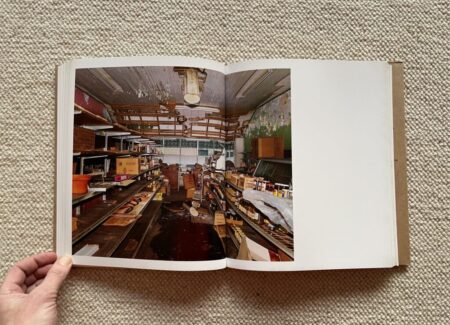

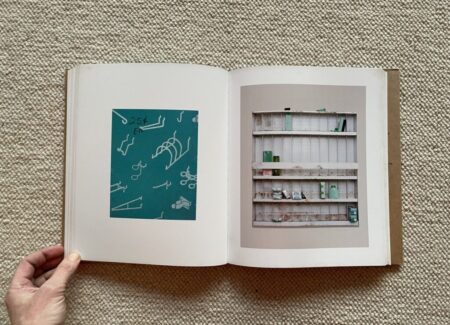

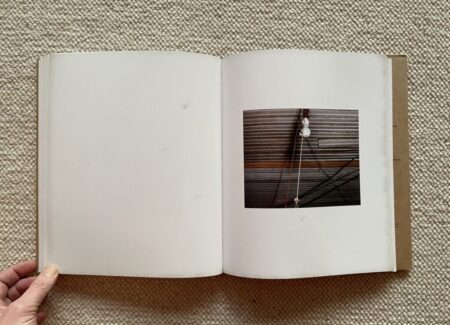

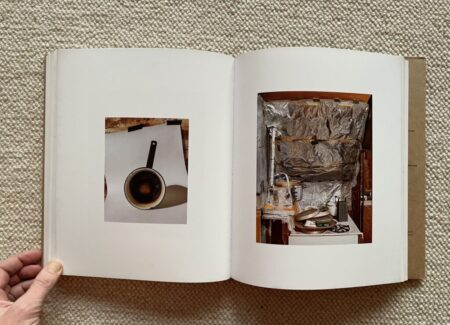

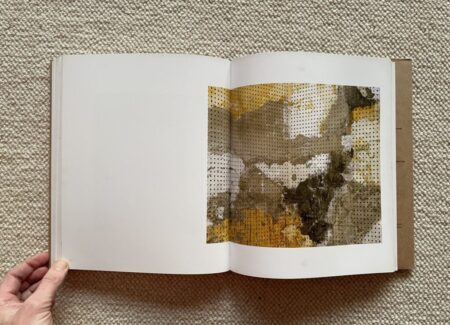

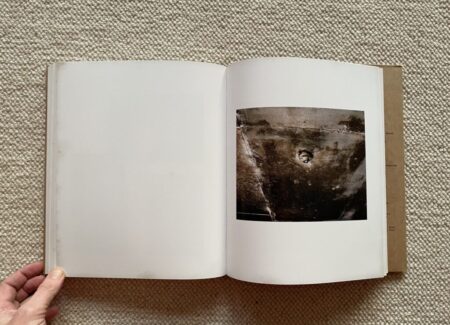

Inside the main store, Patterson does his best to apply systematic order to the scene, with front-to-back and back-to-front images made looking down the aisles, across the shelving at the walls covered in crusty peeling paint, and up at the ceiling bracing and slats. But there is so much stuff crammed onto the wood and metal shelves that it’s hard not to be visually distracted by the scattered time forgotten junk. Refrigerated cases, freezers, metal display racks, and shopping carts further decorate these cluttered views, until we walk through a closed door into the office, where Patterson once again tries to control the largely uncontrolled situation, with structured views of the electrical box, an air vent, and various other decayed surfaces. By the time he reaches the storeroom in back and the living quarters of the owners, the situation has deteriorated even further, with ancient stained sinks and toilets, bare light bulbs amid dangling wires, a folded mattress, and areas of squishy moss fighting with the black mold climbing up the walls to the ceiling. He certainly does an admirable job of making this aging despair look photographically beautiful, particularly in the mottled surfaces of a peg board and a blackened ceiling, but none of us can be altogether surprised when, after the passage of an unknown number of years, we’re left standing in a roofless brick structure with the original murals (from the earlier part of the book) long washed away and the word GONE fingered into the concrete.

Many photographers would have been satisfied with shaping these well-crafted images into a sequenced photobook and leaving it at that. But Patterson does just the opposite; he uses these pictures as a scaffolding on which to hang at least a dozen other mini projects and archival investigations, each with its own path into the larger Gong Co. story. These are then all interleaved together into one grandly integrated flow which jumps from one vantage point to another, weaving them together like the threads of a brocade.

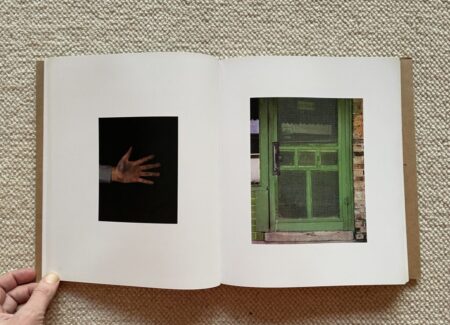

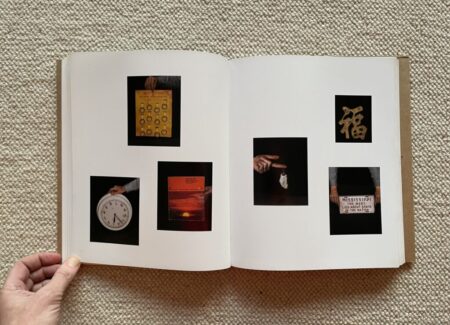

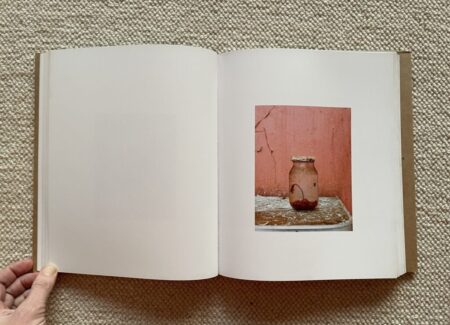

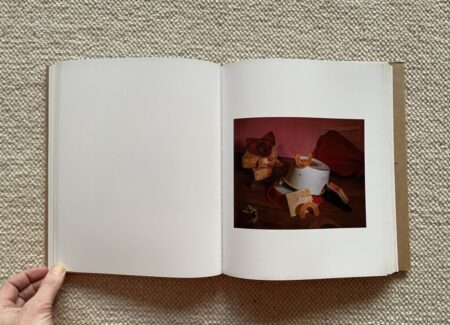

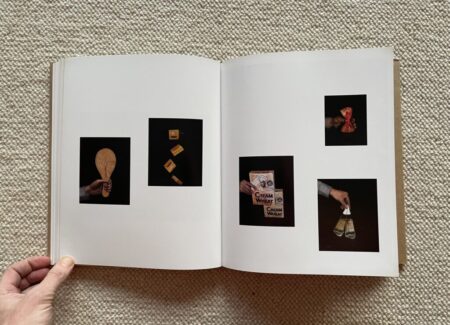

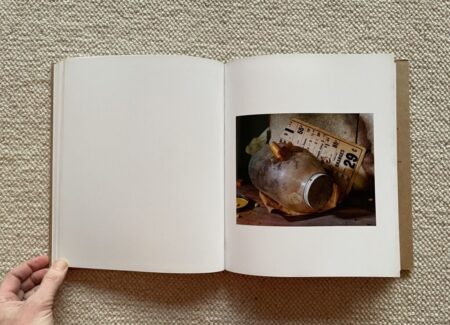

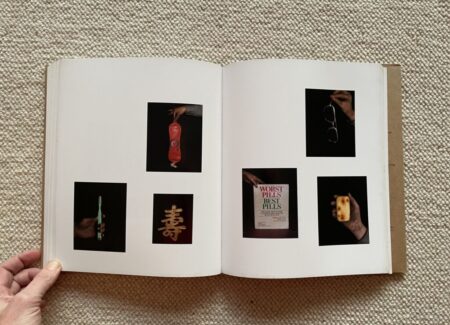

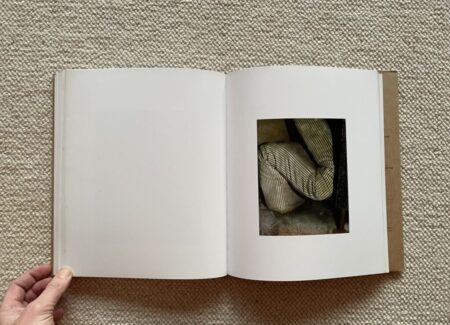

One of the persistent mysteries of Gong Co. is where all the people might be, including the storekeepers or owners; there are no portraits anywhere in the photobook, nor any passing glances of customers, cashiers, stock boys, or any other employees. The only human presence comes in the form of a pair of disembodied hands, which hold various objects from the store against enveloping black backdrops, creating isolated still life images of resonant things found on the shelves. Do the grubby hands belong to the owner of the store (or some descendant)? Or more likely to the artist himself? It’s an unexplained mystery, leaving open the question of who is orchestrating the choices.

As seen in several densely packed spreads of small images, the pictures provide an eclectically informal catalog of the the store’s time capsule offerings, including a set of hanging door bells (likely from the screen door), some key rings, a rabbit’s foot, various Chinese characters, a rusty stove coil, a fly swatter display, a rubber hot water bottle, a clock, a shiny red bow, some SOS scrub pads, two boxes of Cream of Wheat, and various other novelty items. As the pages turn, and we move into the back of the store and living quarters, the still lifes get a bit more personal, including a watch, a toothbrush, some sunglasses, a bar of soap, a bottle of laxative, a packaged roll of toiled paper, and an unmarked bottle of white pills, but we never meet their owner(s). And near the end of the photobook, the hand returns once more holding a stylized sign that says “Please! Don’t ask for credit.”

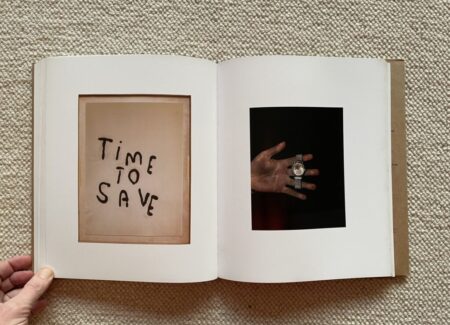

While Gong Co. includes no explanatory essays or supporting texts (aside from some acknowledgements), there are actually quite a number of words, phrases, and communications to be found in its flow. Various store signs, lists, scrawled notes (from the descriptive “Eggs” to the resigned “Going out of business”) and word-covered product packages appear intermittently, perhaps trying to tell us something we’re otherwise missing. Patterson then picks up this idea of obscure messaging with a series of rephotographed monotypes, where he has drawn short phrases out in black ink on paper. Mixing commercial nostalgia with a kind of oblique wordplay, he offers “one mississippi”, “anything and everything”, “all day and every day”, “today is cash”, “old time good”, “time to save”, and “white bread” among other snippets, adding the feeling of a voiceover or pieces of a snatched conversation to the visual mix.

Given the decrepit, decaying, and nearly abandoned state of Gong Co. as the years pass, we might expect there to be some simmering emotions of loss or failure roiling around somewhere, or perhaps some references to the inevitabilities of aging. Patterson refers to these anxieties only fleetingly however, in two images of TV screens (with wiggly graphics referring to “your poison center” and a “nervous stomach”), and in a hidden poster found on the underside of the folded paper jacket. There a carefully arranged still life collage brings together various resonant objects (mouse traps, a blank check, a fly swatter, a two dollar bill), words fragments from packaged products (Tang, Fruitcake, SOS, Pain, Miracle, Magic), and pages from a self help book of some kind (gathering pithy inspiration phrases and title pages from chapters about Crisis and Fear), creating an uneasy visual swirl of memories, coded messages, and unresolved feelings.

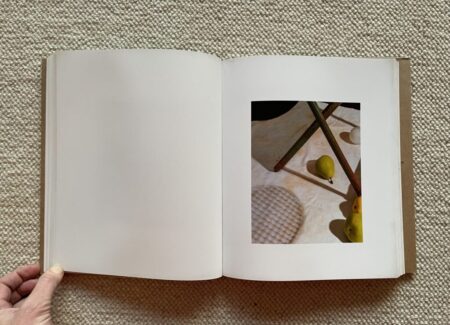

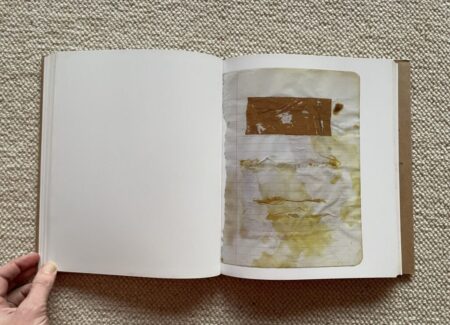

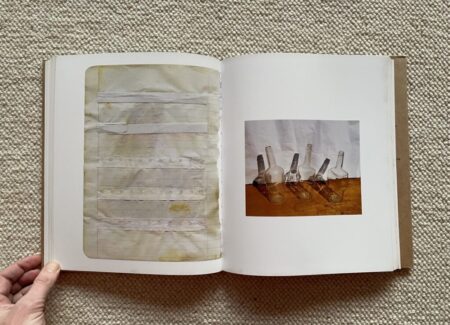

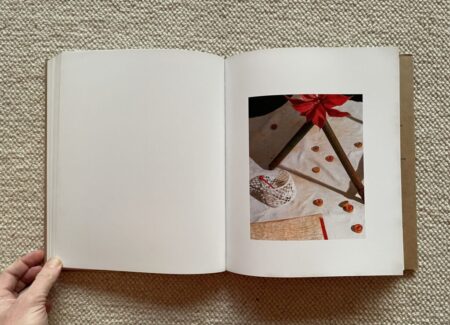

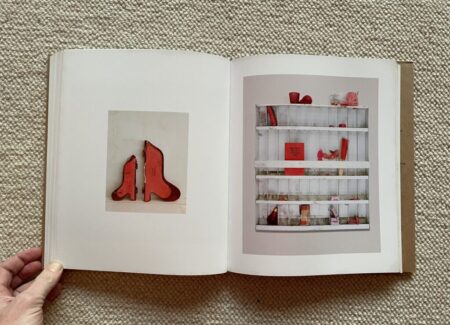

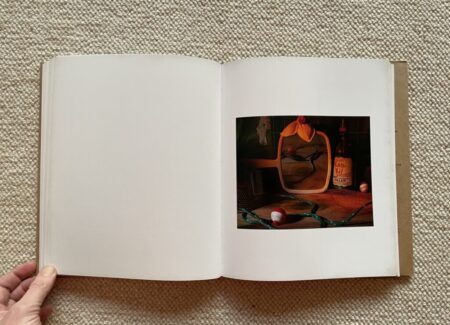

Still other compositional ideas are tried out and then repeated through the page turns, like loose refrains to a song. Patterson arranges items from the store shelves in a white gridded display case, grouping them by color themes, in natural, yellow, green, and red. He sets up isolated still lifes against white paper, selecting an upturned floral trash can, a box of rubber bottle nipples, some ink stamps, three glass bottles (and their shadows), and a paper folder for further inspection. He uses the criss crossed legs of what might be a folding table to divide a red composition of round chess pieces, a game board, and a red flower (like the one on the book’s endpapers) and then a green arrangement with several pears and a light bulb. He gathers up faded notebook papers, many stained a sickly yellow by leftover rat poison or coffee filters, with some turned more toward abstraction via arrangements of more unidentifiable paper shapes. And in a few cases, Patterson constructs more complexly layered still lifes, like one consisting of a mirror, some green rope, some fishing bobbers, a jar of ant and roach killer, and some netting.

Having discovered (and thought about) all of these ways Patterson had engaged with the Gong Co. material, I was sitting at my desk looking the book over once again, and the bright light of the morning streamed in through my office window, hitting some of the seemingly blank pages and alerting me to ever so faint inscriptions found on a few, as though these pages had been written on in pencil and then erased almost completely. The first is found right at the beginning, starting with the idea that “To open a shop is easy; to keep it open is an art.” I then picked out a few others on the last few pages of the book – “all good things come to end”, “yesterday is history tomorrow is a mystery today is a gift”, and “be begin again”. Honestly, these inscriptions are so faint that I’m not sure I have deciphered them correctly (and likely there are others that I never noticed), so they feel a little like intermittent whispers from the dead or ghostly incantations hovering around in the dust of the old store, audible only if we listen closely.

Given that Patterson has offered a dozen or more options for engaging with the Gong Co. store and its related themes in this complex photobook, there are many more opportunities for interpretation here than in most single subject photographic monographs. To me, Patterson’s work feels like a loving fugue or an elegy, where abstract ideas like “American”, “Southern”, “small town”, “general store”, and even “aging” are examined in the specific, and found to be much richer and more nuanced than we might have ever expected. As I went to put Gong Co. on my shelf, I noticed that some of the page edges had become a little oily, like I had been handling the book with slightly sweaty or grimy hands. I now think that these marks were not my doing, but were actually put there by Patterson as well, adding a sense of lived in use to a few pages here and there; at first I was relieved to conclude I hadn’t scuffed the book myself, but then I simply had to admit that there was some very intentional magic going on. In this way, Gong Co. fully rewarded the time I invested in it, forcing me to see a forgettable old country store as something quite a bit more subtly astonishing.

Collector’s POV: Christian Patterson is represented by Robert Morat Galerie in Berlin (here). His work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.