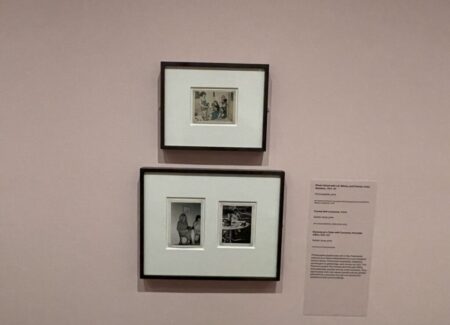

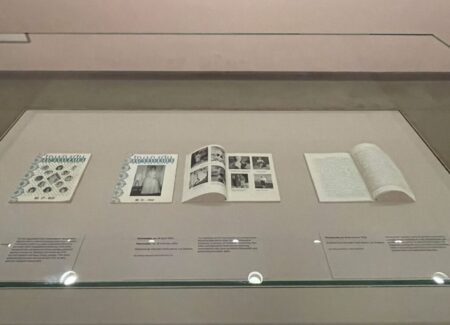

JTF (just the facts): More than 100 black-and-white and color photographs, framed in dark wood and matted (often in clusters), and hung against light pink walls in a series of rooms (Gallery 852) on the second floor of the museum. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- Unknown photographers: 33 gelatin silver prints, 1959, 1950s, 1960-1963, 1960-1966, 1961, 1963, 1964, 1960s, sized roughly 3×4, 3×5, 4×3, 4×4, 4×5, 5×3, 5×4, 6×4, 7×5, 9×7 inches

- Unknown photographers: 5 instant diffusion transfer prints (Polaroid), 1959, 1950s, 1960-1963, 1960s, sized roughly 3×4, 4×3 inches

- Unknown photographers: 78 chromogenic prints, 1955-1963, 1960, 1960-1963, 1960-1964, 1961, 1962, 1963, 1963-1964, 1963-1965, 1964, 1964-1968, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1960s, sized roughly 2×4, 3×3, 3×4, 4×3, 4×4, 4×5, 5×3, 5×4, 7×4, 7×5, 9×6, 9×7 inches

- Andrea Susan: 10 chromogenic prints, 1955-1963, 1962, 1964, 1964-1968, 1965, 1966, 1960s, sized roughly 3×2, 3×4, 4×3, 4×4, 4×5, 5×4, 7×4, 7×5 inches; 6 gelatin silver prints, 1960-1963, 1964-1968, sized roughly 3×4, 4×3, 5×4, 7×5 inches; 1 instant dye diffusion transfer print (Polaroid Type 108), 1965-1969, sized roughly 3×4 inches

- Edith Eden: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1960-1963, sized roughly 4×4 inches

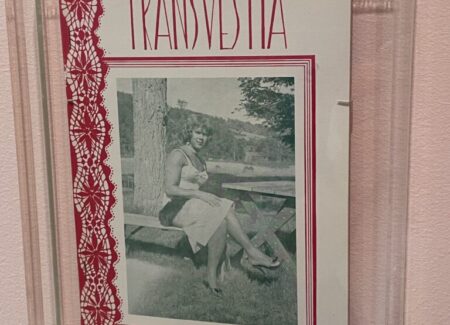

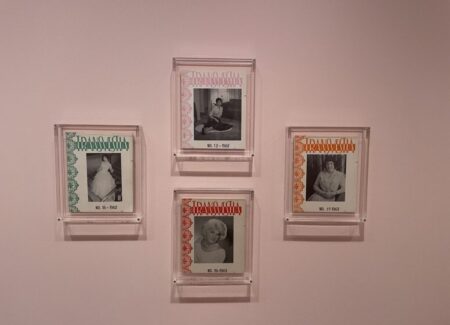

- 8 periodicals, 1961, 1962, 1963, sized roughly 8×7 inches

- 1 Super-8 film transferred to digital video, 1960s, color, silent, 2 minutes 5 seconds

- 1 business card, 1960s

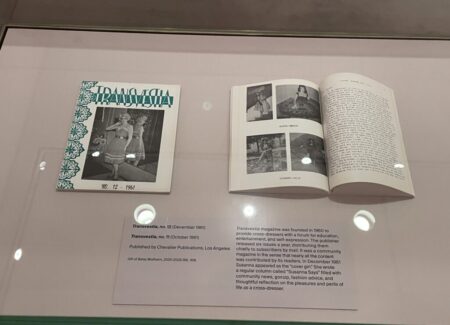

- (vitrine): 2 periodicals, 1961

- (vitrine): 3 periodicals, 1960, unknown photographer: 1 chromogenic print, 1960s, sized roughly 5×4 inches; unknown photographer: 1 gelatin silver print, 1967, sized roughly 3×4 inches

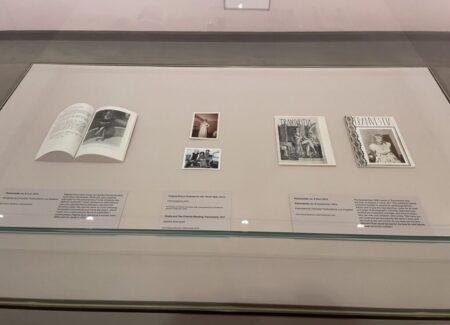

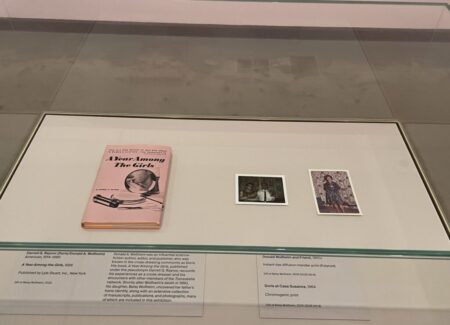

- (vitrine): 1 book, 1966; unknown photographer: 1 instant dye diffusion transfer print (Polaroid), 1960s, sized roughly 3×4 inches; unknown photographer: 1 chromogenic print, 1964, sized roughly 5×4 inches; 4 periodicals, 1960, 1962

Comments/Context: In the past decade or two, vernacular imagery has been embraced and legitimized by cultural institutions as a recognized subgenre of photography, in ways that it hadn’t been accepted previously. It was not so long ago that family albums, casual snapshots, photobooth strips, and other anonymous photographs weren’t paid much attention by museum curators, unless they were were considered artifacts, archives, or documentary evidence related to a particular artist and his or her life. But that attitude has fundamentally changed of late, most notably when these photographs tell stories and document lives that have been previously overlooked or marginalized. Passionate vernacular photography collectors have long scoured antique shops, swap meets, tag sales, and abandoned storage containers in search of under appreciated treasures, and a few, like Peter Cohen, Lee Shulman, and Thomas Sauvin (to name just a few), have amassed thousands of prints that capture complex (and often unique) visual histories that fall outside the traditional boundaries of fine art. These collectors were far ahead of the more recent trend, and their massive collections now provide important raw material for further historical research, as well as for newer forms of artistic exploration and experimental image reuse.

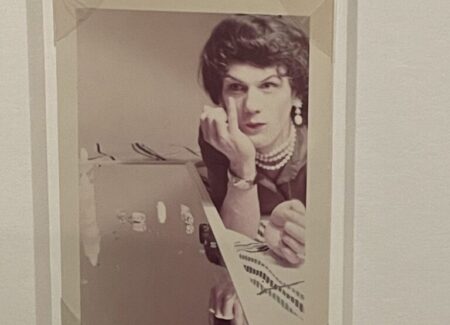

The backstory to the vernacular photographs in this well-edited show follows a familiar pattern – a cache of unidentified photographs found at a flea market in New York in 2004. The pictures captured a group of 1960s era cross-dressers, who met in the city and also upstate at private resorts in the Catskills mountains. At that moment in pre-Stonewall America, cross-dressers (who called themselves transvestites at the time, a term that has fallen out of common usage) largely stayed in the shadows, many leading double lives as married men with families, children, and established careers. The rediscovered archive of photographs is filled with a consistent sense of acceptance and freedom, documenting a supportive community of people exploring their femme identities in an era of rigid gender roles.

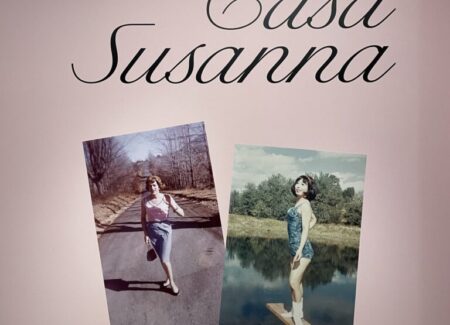

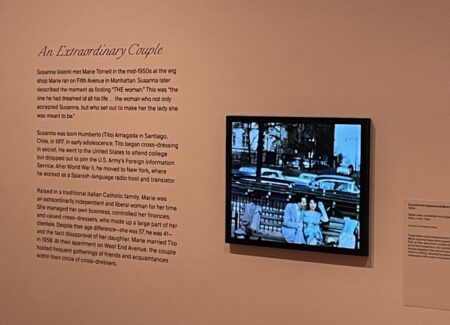

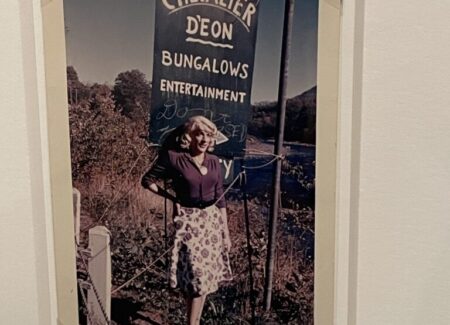

In the years since the pictures were first found, additional research has filled in many of the previously missing details. The “Casa Susanna” narrative revolves around a single couple: Marie Tornell, who ran a wig shop on Fifth Avenue, and Humberto (Tito) Arriagada, who called herself Susanna Valenti. The two met in the mid-1950s, married in 1958, and hosted gatherings of cross-dressers (many of whom frequented Tornell’s shop) at their apartment on the Upper West Side. In 1960, the couple started bringing the community together at a resort in the Catskills owned by Marie, which they named “Chevalier d’Éon” after an 18th century cross-dressing French spy. The resort (which included a converted barn where the group could stage drag shows and other performances) was in business for several years, and was eventually sold in 1963, to be replaced by a smaller house bought by the couple a few miles away, which became “Casa Susanna”; it received guests until 1967, when Marie was disabled by a serious fall, and the couple ultimately sold the house in 1972.

Contemporary photography is filled with artists using their cameras to explore facets of identity (male, female, or other) or to create personas that are made to be photographed, so the Casa Susanna pictures offer a vintage (or baseline) example of those current impulses. A quick look at the credit labels for many of the prints included in this show finds more than a few coming from the collection of Cindy Sherman, which makes complete sense, given her own interest in photographic variations of perforative femininity. Seen as a group, the Casa Susanna photographs (both posed and candid) affirm a particular sense of true self, so much so that they were then shared with others, at the gatherings, by mail, and in issues of Transvestia magazine.

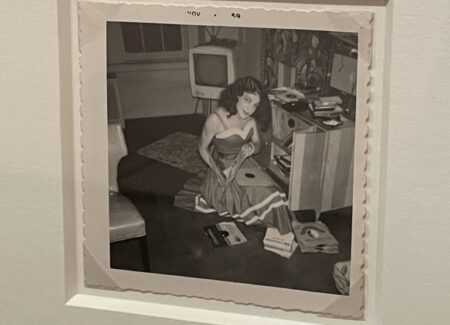

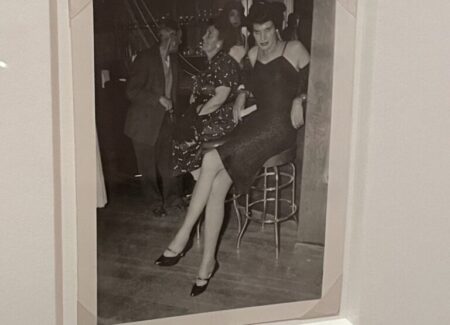

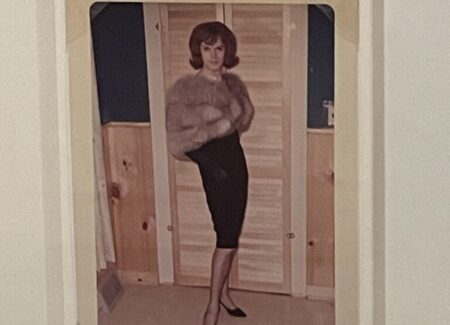

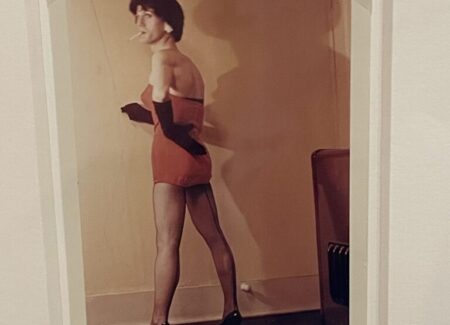

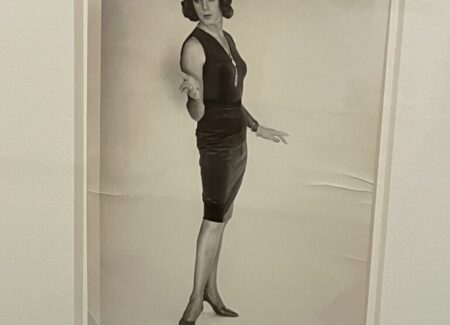

In a loosely chronological progression, the show begins with introductory images of Susanna (and Marie), first in their apartment and other like-minded homes around town. The snapshots center mostly on Susanna, as she poses in dresses in various living rooms, in some cases with more performative or seductive setups, like kneeling by a record player, dancing with castanets, dressed in a bodysuit, standing by a mirror, or showing some leg with friends. The pictures are filled with the playful confidence of someone finally feeling safe and comfortable (often in the company of friends), trying on her persona and slowly filling it out.

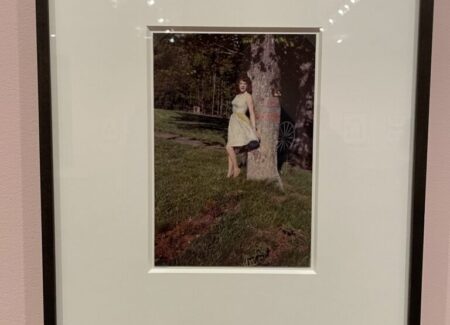

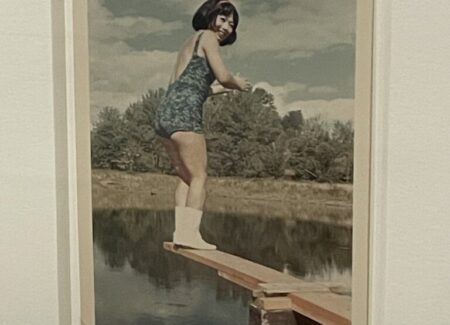

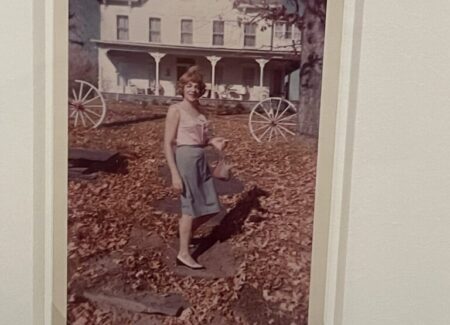

The scene then shifts from city to country, with urban interiors giving way to moments both indoors and out, first at Chevalier d’Éon and later at Casa Susanna. There are many posed photos in front of the sign, near the front stoop, on the steps, on the porch, and elsewhere in the yard and around the main building and bungalows at Chevalier d’Éon, the settings providing a validating backdrop for the community members. Inside, images of playing Scrabble, working in the kitchen, and sitting on barstools quickly transition into a selection of color pictures from the many stage productions and performances, the red curtain and colorful dresses (and costumes) creating a heightened sense of performative drama. When the action shifts to Casa Susanna, a similar photographic aesthetic keeps things relatively consistent, with outdoor poses near trees, next to a wagon wheel, and in swimsuits (on the diving board) matched by groups posed together near the building.

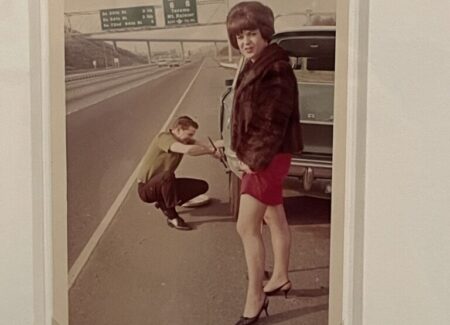

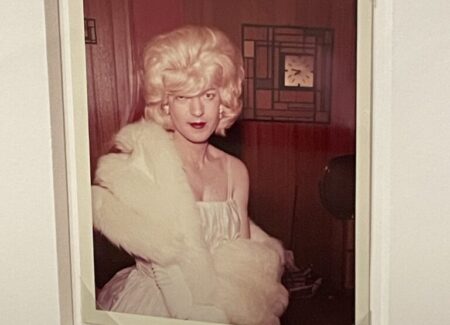

Some of the most engaging imagery in the show is to be found near the end of the installation, where the photographs have been grouped into sets, highlighting different aspects of the feminine role playing (for the camera) taking place. In some cases, the tropes of fashion photography help define aspirational feminine glamour, in poses featuring expensive furs, with handbags, in lingerie, and wearing a wide variety of wigs; the setups with flashy cars are some of the best, particularly one with Kate standing next to her car as a man squats down to fix the tire in the background. In other images, the ideal being chased was a more modest sense of middle-class domestic living, where successfully “passing” as a respectable housewife was the goal. Here the pictures feature chores like watering the garden, sweeping the floors, and working in the kitchen (in house dresses and aprons), as well as setups with televisions and Christmas trees to signal festivity and holiday cheer. A few pictures actually capture playful photo shoots in action, the cameras themselves becoming part of the visual story being documented. Again and again, we watch as personas are crafted and roles are played, each carefully staged moment a bravely optimistic reach for approval.

In a contemporary world now filled with selfies and performative image making, the Casa Susanna archive provides ready context for the idea of photography as an active means for documenting alternative identity. But more compellingly, this show is a story of hidden isolation turned into welcoming community, where finding acceptance was like “stepping through the door into another universe”.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices, and given that most of the photographers included here are unknown, we will forego our usual discussion of gallery representation relationships and secondary market histories.