JTF (just the facts): A total of 37 photographs exhibited in the foyer and the main rooms of the gallery. Seven are color pigment prints, the others are gelatin silver. Most are dated either 1957 or 1959, with one from 1960. None are vintage. All are open-editioned, estate-stamped, and sized either 8×10, 11×14, or 20×24 inches. A vitrine in the foyer contains copies of the magazines Esquire and Holiday, where several of the photographs originally appeared in the late 1950s. (Installation shots below.)

A companion book Burt Glinn: The Beat Scene was published in July 2018 by Reel Art Press (here). (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: The Ab-Ex artists and their later compatriots, the Beat writers, didn’t shy away from the camera. Defining themselves in the 1950s against the rigid conformity of Eisenhower’s America, they argued among themselves and fostered their movements in small-circ. art and poetry magazines while at the same time learning to appreciate to value the publicity that could only happen in mainstream outlets.

After all, perhaps the iconic photograph of the New York School was “The Irascibles,” Nina Leem’s 1951 group portrait of 18 scowling artists expressing their displeasure with a timid show of contemporary art at the Met. The image ran in Life, the epitome of middle-brow America.

Jackson Pollock had already by that time received the star treatment from the magazine. It gave him a three-page spread and headlined its 1949 profile: “Is He the Greatest Painter in the United States.” He must have seen how often his hero Picasso had posed for photographers, for Brassaï, Gjon Mili, Robert Capa, as well as a host of lesser-knowns. Picasso was a genius and enjoyed it that journalists thought so, too.

The Beat writers were just as media friendly. Jack Kerouac gave interviews freely throughout his life and even went on “The Steve Allen” TV show in 1959. The affable Allen Ginsberg, ready to be quoted in the press on almost any topic during his long life, also avidly photographed his wide circle of friends.

The photographs of Burt Glinn (1925-2008) in this show, and its accompanying book, testify to his easy rapport and symbiotic relationship with some of the leading artists and writers around New York during the late ‘50s. An associate member of Magnum in 1951, a full member after 1954, he was among the first Americans (along with Eve Arnold and Dennis Stock) asked to join the illustrious collective.

Although Pollock had died in 1956, before these pictures were taken, Glinn photographed many of the middle-aged Ab-Ex painters of that first generation (Willem De Kooning, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman), usually at art openings. He also frequented the jazz clubs (the Five Spot Café) and coffee houses (Seven Arts Coffee Gallery) where a younger crowd of artists and writers (Larry Rivers, Frank O’Hara) were hanging out to smoke and drink.

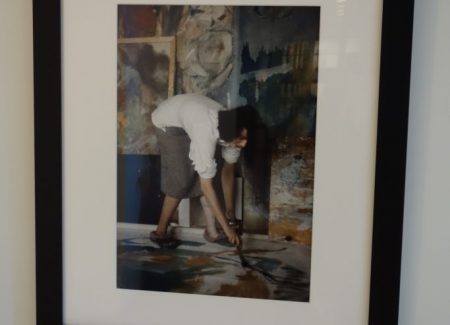

Helen Frankenthaler was a willing subject, letting Ginn photograph her standing on a large canvas, moving paint around with her hands and slippered feet. (He and she both must have been aware of trying to recreate Hans Namuth’s 1951 films and photographs of Pollock painting on the floor and ground.) Bewitchingly attractive, she appears in several other scenes by Glinn: hugging David Smith during a visit to her studio and arm-in-arm with Joan Mitchell and Grace Hartigan at a gallery opening of Frankenthaler’s work.

Ginsberg was another happy collaborator with Glinn. A 1957 photograph of the poet, seated with Gregory Corso and the publisher Barney Rosset on a bench in Washington Square Park, dates from around the time that Howl was the target of a famous obscenity trial in New York. Published the year before by City Lights, the poem was already notorious (and popular) because of its sexual language. In one pose here, Ginsberg holds his index finger up in stentorian style. If the laughing response of his friends was also at Glinn’s expense—the square from the magazine world assigned to document “the beatniks”—it’s not a cruel inside joke. They could also have been high.

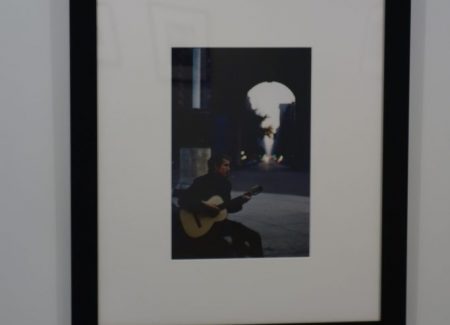

Kerouac also popped up often in Glinn’s contact sheets. At the Seven Arts Coffee Gallery, he is dressed almost like a parody of a Beatnik, wearing a raincoat, flipped-around hat, sunglasses indoors—and receiving welcome attention from a young woman. The musician David Amram had an active role in various Greenwich Village scenes—John Strausbaugh’s 2013 history was one of that first to give him ample credit—so it’s good to see that Glinn photographed him blowing hard on his French horn, an unorthodox instrument in the context of jazz, at the Five Spot Café.

The paintings that Glinn saw in the studios and galleries seem to have influenced how he photographed. A dual color portrait in silhouette of the R&B alto saxophonist Earl Bostic and his trumpet player, playing chess in 1960 at the Blackhawk jazz club in San Francisco is carefully set against a wall of orange and yellow stripes, which are framed to look like a Barnett Newman.

The absence of African-Americans among the writers and painters here is striking, Leroi Jones (who later renamed himself Amiri Baraka) being the only one. Like too many of Glinn’s subjects, he is shown gazing out a tenement window. Photographers have created stereotypes of artists, as Barbara Kruger demonstrated in an amusing show of artist portraits she selected from MoMA’s collection in 1988, and Glinn reinforces a lot of the usual meditative poses.

This is 35 mm. work, done for public consumption, on assignment for magazines such as Esquire and Holiday. Everyone is photographed as anyone would like to be seen: as serious, thoughtful, young (except for the elder statesmen Hans Hoffmann and Alexander Kaldis), vigorous and, above all, physically attractive. There isn’t an ugly man or woman on the walls. Nor is anyone yet visibly dissipated with alcohol or riddled with lung cancer.

These images may not have the hermetic integrity of Dave Heath’s or John Cohen’s quirkier views of the downtown scene. But Glinn was a cool cat in his own way and sympathetic to the artistic upheavals he was seeing. To glide around sometimes difficult people and photograph them as unobtrusively and respectfully as Glinn does here is a commendable skill.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show range in price from $1500 to $3500, based on size. Glinn’s work has been intermittently available in the secondary markets over the past decade, often in London sales. Recent prices have ranged between roughly $1000 and $12000.