JTF (just the facts): A paired show, containing a total of 25 color photographs by Luisa Lambri and Bas Princen. The works are framed in black/white/wood and unmatted, and hung against white walls in a series of 3 connected gallery spaces, in addition to the entry area and the book viewing area in back. The show includes 14 inkjet prints from 2016 by Lambri and 6 inkjet prints from 2016 and 5 chromogenic prints from 2016 by Princen. No physical size or edition information was provided. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: As I left my recent visit to this extremely unassuming but quietly thoughtful show at the Met Breuer, I was waved down by a friendly staffer in the lobby, who wanted to ask me a few questions. After answering the standard background queries (who I was and what had brought me to the museum), the man offered me an open-ended “what did I think of the museum” kind of comment inducer. After thinking for a moment, I said something to the effect that this was museum that was still trying to figure out who (or what) it was. This reply puzzled him mightily, but he dutifully wrote it down and sent me on my way.

It’s been a half dozen years since the deal that brought the former home of the Whitney into the arms of the Met, and after some much needed renovations and tune ups (or clear aways, depending on your perspective), the rechristened Met Breuer has been host to a handful of exhibits, most notably two superlative shows of the work of Kerry James Marshall and Diane Arbus. But even with these successes under its belt, it still very much feels like a work in progress. Ostensibly the new home of modern and contemporary art for the Met, or at least a handy adjunct to what it has already on Fifth Avenue, the Met Breuer hasn’t fully found its footing just yet, and it feels like a place that lacks a completely coherent vision or direction. What is this place? What does it stand for? How does it fit into the rest of what the Met is doing? And how can the Met make it its own, rather than simply stumbling along as an interloper in the “old Whitney”? These and other questions remain tantalizingly fluid.

Tucked away on the top floor, in an exhibit that few will likely see or entirely comprehend, is actually the beginnings of an answer. At it core, it starts by acknowledging that this location isn’t a clean slate – this particular place will always be defined by its singular architecture, and that to discover or build a durable new identity going forward, the museum will need to go back to the very building itself (and its architect Marcel Breuer) to find the initial clues to what can actually come next. And the people who can offer critical input into that future solution will be (and must be) artists.

So this show brings together two established artists/photographers, Luisa Lambri and Bas Princen, who have built their artistic practices around responding to architecture and asks them to consider and interact with the Met Breuer (and a few other buildings designed by Breuer as context). To call these two “architectural photographers” misses the point entirely – their goal is not to routinely document famous buildings as much as it is to use them as a jumping off point for their own artistic explorations. And so the exhibit is in effect an attempt to figure out a rough baseline for what this place is and what it might offer, at least artistically. The fact that their photographs have then been installed in the very building they are responding to adds another layer of resonance to the project.

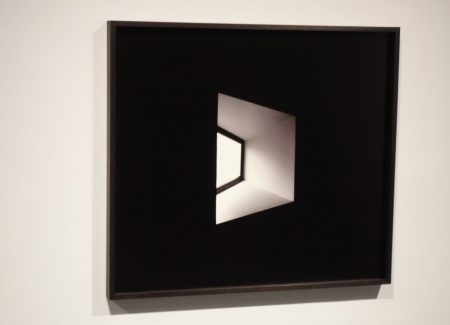

In Lambri’s case, her studies of architecture have largely revolved around how light plays across the surfaces of a building, particularly when transparency and opacity shift with the passing of time. At the Met Breuer, she turns the single polygon of a deeply cut window into a sequential investigation of shifting brightness and shadow, the surrounding wall becoming an inky black expanse of nothingness. Each exposure captures the cast light inside the geometric enclosure, moving from complete whiteness to soft transparency (with a tumble of white blossoms in the background); when the viewing angle is more severe, the window vanishes, leaving behind a minimalist composition of angled planes that collects the available light. In these photographs, Lambri lingers over the effects of passing time, showing us that building responds differently to the changing conditions, almost like a living being.

When she turns her camera to other Breuer-designed buildings (the UNESCO headquarters in Paris and the Saint John’s Abbey Church in Collegeville, Minnesota), she once again opts for an investigation of how their surface details handle light. Lambri makes us look more closely at white sheathing rectangles of stone that have darkened with age, revealing complex topographies of mottled spots, natural veining, and general wear that feel porous in their tactile smoothness. She does the same with hexagonal honeycomb-like openings that filter incoming light, elongating them into tall narrow arches or playing with shadowy darkness that flits across their concrete surfaces.

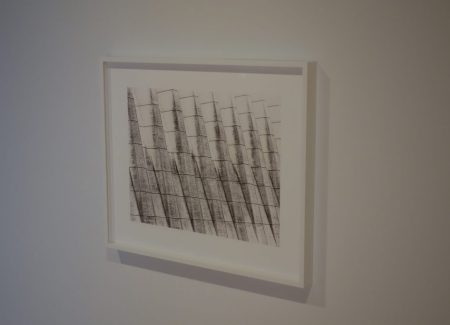

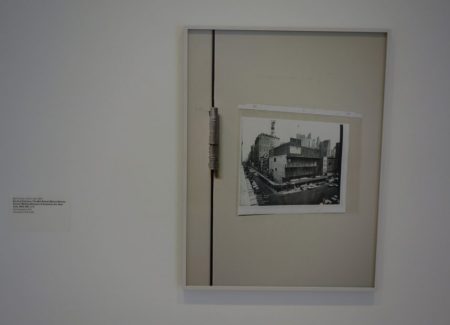

For Princen, the Met Breuer challenge was somewhat more complicated, as many of his previous photographs of architecture have taken in the entirety of how the forms of a building interact with its surroundings. In his supporting images (from the Breuer-designed IBM Research Center in La Gaude, France, the Saint John’s University Library, and the UNESCO headquarters), he captures graceful swoops of facades and circular pavilions as they poke through nearby greenery, and considers the step-wise twist of a concrete staircase against a jagged city skyline. Once inside, he turns his lens on the bulkiest of Breuer’s blocky support columns, giving us a feel for their immense weight and bulkiness as well as their understated formal elegance. His images of the Met Breuer celebrate its yawning voids and its scratchy surfaces, pushing us to recognize its active sculpture of open space – its walls and supports define the interior with far more personality and grace than any white slab of drywall ever could. Princen’s photographs encourage us to revel in this thick cave-like openness (and intimate tightness in a few spots) of the Met Breuer, its burly massiveness an advantage not a hindrance.

What I like best about this exhibit is that it posits that artists are the stakeholders that just might be able to chart a path forward that takes the mastery and joy of the Breuer building into account (its agonizingly slow elevator during crowded periods notwithstanding). It also states clearly that an authentic new vision for the museum (in this space) will need to artfully coexist with the building rather than undermine or undervalue it. Whether the Met ultimately has the institutional flexibility (and the resources) to effectively harness its newest asset remains to be seen. But this overlooked show sends the straightforward signal that it is trying to understand the nuances of the problem and is leveraging the fresh-eyes insights of artists (as well as administrators) to move ahead with intelligence.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show (with some commissioned images), there are of course no posted prices. Luisa Lambri is represented by Luhring Augustine in New York (here), Marc Foxx in Los Angeles (here), and Thomas Dane Gallery in London (here). Bas Princen is represented by Van Kranendonk Gallery in the Hague (here).