JTF (just the facts): A total of 26 black and white photographs, generally framed in white and matted, and hung against cream colored walls in the main gallery space and the entry area. All of the works are gelatin silver enlargement prints on ferrotyped paper, made between 1931 and 1936 (many are vintage or near vintage, with a few printed in the 1950s or 1960s). Physical sizes range from roughly 7×5 to 20×16 inches (or reverse), and no edition information was provided on the checklist. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: When an artist dies, the responsibility for the remaining artworks often falls to a spouse, a relative, or in some cases, a long time friend or studio associate. Some families set up estates, trusts, and other legal entities to actively manage the artist’s legacy, while others simply place the artworks in safe keeping of some kind, awaiting an opportunity to quietly place them with interested buyers.

Brassaï passed away in 1984, and since that time, there have been plenty of gallery shows, comprehensive museum retrospectives, and major sales of his work, so it would be reasonable to assume that whatever was left behind when he died was long ago picked over and sifted through by industrious gallery owners, museum curators, and other interested parties. But as is often the case, family members tend to squirrel away some of their favorites, living with them in their homes and keeping them out of the purview of the art market machine. And just when we think the well might have run dry for rare vintage examples of a deceased photographer’s best work, sometimes we get lucky and a few gems pop out from these family collections.

Such is the case with this show of Brassaï’s 1930s work drawn from the collection of Madame Brassaï. It gathers together a selection of prints from the photographer’s various Parisian night projects, from moody nocturnal streets and the prostitutes and hoodlums that inhabited them, to the more lively interior activity at bars, nightclubs, and brothels. The edit mixes true classics (including one bar image enlarged for an early 1950s exhibition at MoMA) and more obscure variants and secondary prints that expand the usual story of Brassaï’s nighttime wanderings.

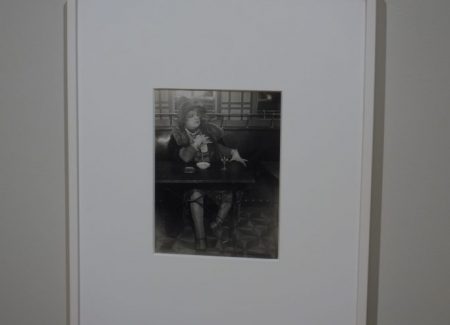

While this show doesn’t teach us much about Brassaï that isn’t already well and thoroughly documented elsewhere (including in a recent retrospective catalog, reviewed here), that familiarity doesn’t diminish the experience of tagging along as he lingered in the underbelly of between-the-wars Paris. The strength of this particular group of pictures lies in the cafes, bars, and dancehalls, where Brassaï somehow found way to document people smoking, drinking, carousing, and even dancing, all without making himself intrusive to the point of obvious posing.

While cafe life in Paris has been documented by many master photographers, Brassaï’s images of couples and groups at tables, his subjects surrounded by other tables full of people and the reflections of mirrors that fill the walls, brim with life and personality. The gestures, expressions, and details tell so many small stories: an arm around a shoulder, a swaggering drag on a cigarette, the smiling shared embrace of lovers, a man with his dog, a woman bored by her date, another looking over at another table, a resigned hand in a chin, and even the famous La Môme Bijou with her fingers and neck encrusted with costume jewelry. Some of the best of these compositions not only capture these gestures with attentive sensitivity, the mirrors create layers of foreground and background, or looks and reactions that bounce around the frame.

When the band got going, the movements of dancing gave Brassaï more opportunities to get in close without being a distraction. He captured the happy close quarters of couples of all kinds, not only men with women, but same sex couples, mixed race couples, and other less accepted pairings, all within the jostling fun of crowded rooms. Few pictures from this period document these underground clubs with such honesty and openness.

Other highlights from this show include the easy going frankness of the nude women at Chez Suzy, the hazy dark seduction of the opium parlors, and the extravange of the floor shows filled with can can dancers. Even when Brassaï caught his subjects in quiet moments, his pictures engage us with the energetic thrum of real life, the freedoms of the night allowing Paris to get comfortable.

For eclectic rarity alone, this sampler merits a quick refresher on the durable joys of Brassaï. It’s a blast from the past reminder that not only did he thoughtfully excavate the margins of an eternal city, he did it with an eye for human detail that made the place and time feel special.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show range in price from $18000 to $110000. Works by Brassaï are readily available in the secondary markets, with prices generally ranging from roughly $2000 to $60000, with a few vintage outliers in six figures.