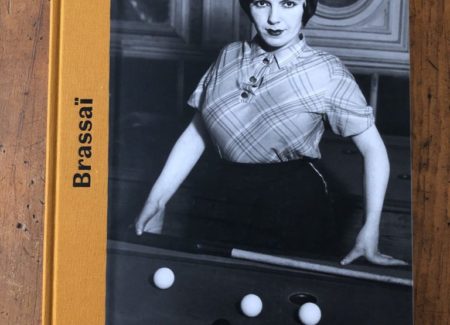

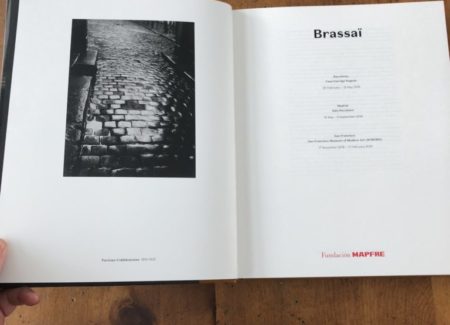

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2018 by Fundación MAPFRE (here). Hardcover, 9.5 x 11.75 inches, 368 pages, with more than 2oo black and white and color reproductions. Essayists include Peter Galassi, Antonio Muñoz Molina, and Stuart Alexander, who also provides a chronology and, with Galassi, a selected and annotated bibliography. Accompanies a retrospective exhibition, organized by Galassi, that opened at Casa Garriga Nogués in Barcelona (February 20-May 13, 2018) and will travel to Sala Recoletos in Madrid (May 31-September 2, 2018) and SFMOMA (November 17, 2018-February, 17, 2019). (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Gyula Halász (1899-1984), better known as Brassaï, had a remarkably unclouded life. The two world wars that devastated the European continent did not gravely effect him, save for a case of typhus in 1919 and a few years of looking over his shoulder in the south of France to avoid suspicious Nazis during the 1940s. Even if, like many Hungarians, he felt obliged to adopt the customs and languages of other nations in order to join a wider 20th century cultural conversation, his émigré status never hindered him for long. When he moved to Berlin in 1920, he avidly read Goethe whose writings thereafter became a lodestar. Heading to Paris in 1924, he settled in Montparnasse and began to identify himself by a pseudonym, Brassaï, that only a decade later would become know far beyond his native country. (The name in Hungarian means “from Brassó”—his home town in Transylvania—chosen perhaps to remind himself where he came from.)

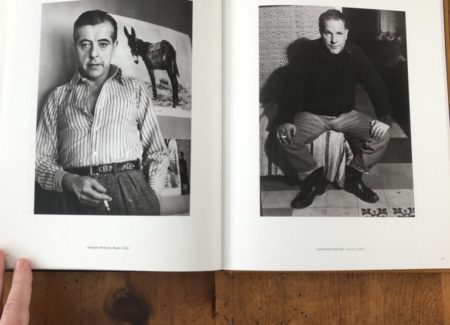

His later autobiographic writings indicate that two of his regrets in life were that he had not succeeded at his initial artistic endeavors, poetry and painting. If so, he quickly compensated for these failures when he took up photography in earnest around 1930. His first book, Paris de Nuit, published in 1932, secured him a lifetime of assignments from European and American magazines, editors typecasting him as an urbane connoisseur of shadows and louche behavior. Artists from opposing camps, Surrealists and social-minded photojournalists, tried to enlist him to their causes, and he deftly kept his distance from both without alienating either. A gregarious soul whose stories, jokes, and intelligence made him welcome at everyone’s table, he met or befriended most of the writers, painters, sculptors, filmmakers, and photographers of note who passed through Paris over a span of 60 years. What’s more, they were honored to know him, too.

Never being out of fashion hasn’t altogether benefited him, though. Because his career hasn’t needed discovery or rehabilitation, his mastery can be taken for granted. The rules that guided his artistic practice weren’t doctrinaire; he didn’t strictly distinguish between staged pictures and those he had captured à la sauvette. He experimented in the darkroom, cropping willfully. As a result, unlike photography’s more militant purists—Stieglitz, Adams, Cartier-Bresson, Capa, White, or Winogrand—he never attracted zealous followers or created sworn enemies. Even surrounded by boisterous company, Brassaï was the cat that walks alone.

Museums saluted him often during his life, and appreciation has only gained momentum since his death. His photographs of ‘30s Paris are guaranteed box office. MoMA included him in several shows between the 1930s and 1950s, capped by a retrospective in 1968. Since then, a number of posthumous retrospectives have taken his full measure: at the Musée Carnavalet in 1988; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston in 1999; the Centre Pompidou in 2000; and the Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 2011. Substantive catalogs have accompanied all of them.

This latest major exhibition builds on previous efforts but is more of a distillation than an expansion. Brassaï was a restless artist with many talents. Most aren’t on display here. Galassi has decided not to exhibit the sculptures, engravings, drawings, tapestries, scene designs, and writings found in some earlier shows. Instead, Brassaï presents him solely as a photographer, and only in black-and-white. (His color work from the 1960s is mentioned but not displayed.)

The selection doesn’t alter the traditional view that Brassaï peaked before he turned fifty. Of the 200 or so prints, the greatest number are dated between 1932-39. The second largest group are from the 1940s. There are roughly 20 from the 1950s, and none later than 1960, except one from 1971 of an abstract female sculpture he had carved.

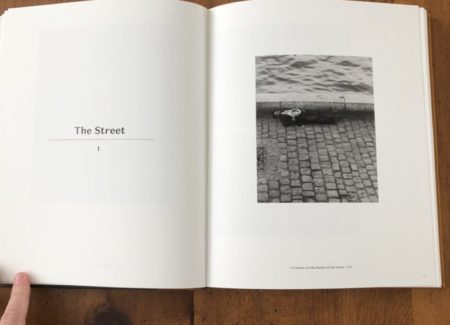

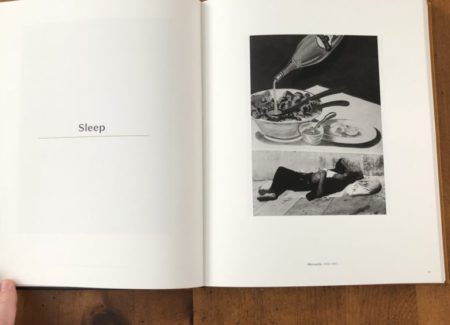

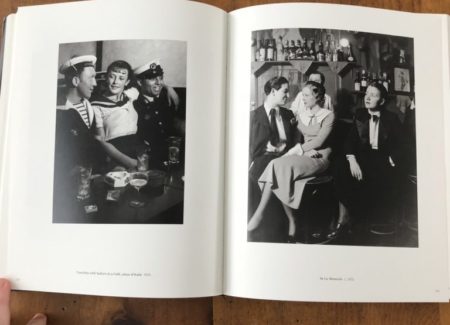

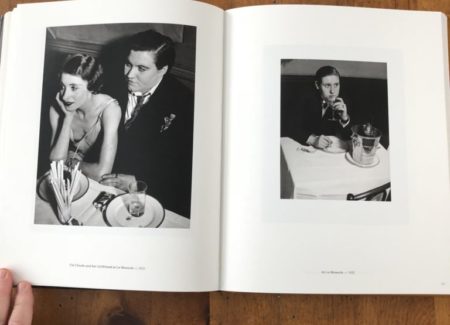

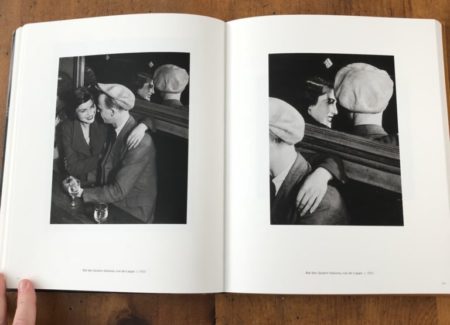

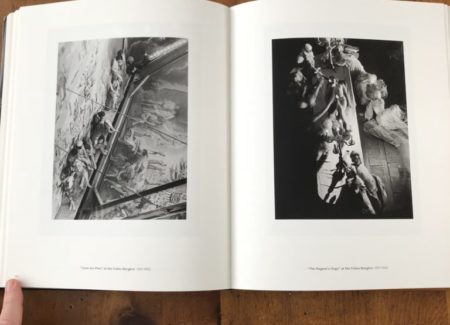

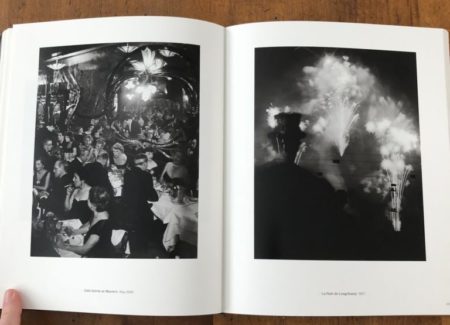

The organization is also not a radical reshuffling of the usual categories. The plates are divided into 18 sections: Self Portraits; The Street (2 sections); Paris by Day; Sleep; Paris at Night (2 sections); Minotaure; Pleasures (4 sections); Society; Personages; Graffiti; Body of a Woman; Places and Things; and Portraits: Artists, Writers, Friends.

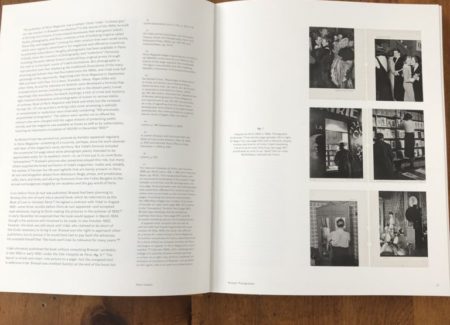

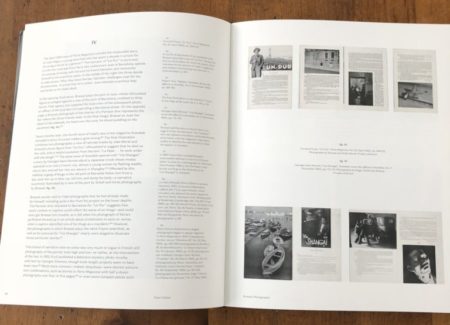

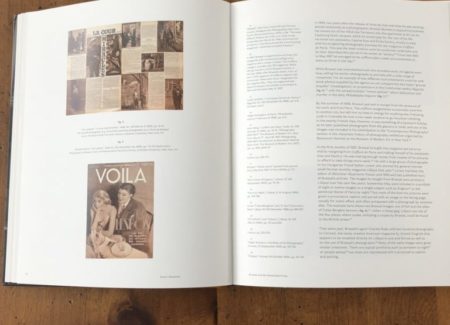

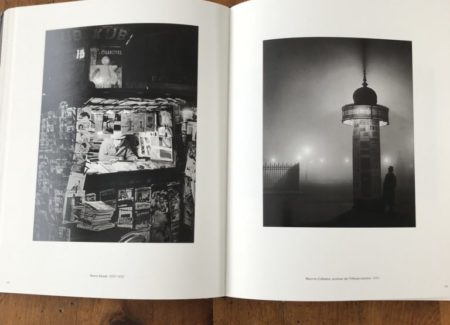

What’s original about this retrospective is the unprecedented focus on Brassai’s career in magazines and his continual, wily independence from them. In the absence of a market for prints before the 1970s, freelance photographers earned their living by selling reproduction rights to their images. Brassaï’s savvy understanding of what Galassi calls “commercial modernism” led him to publish popular books, such as Paris de Nuit, and to work for a hodge-podge of publications that nonetheless paid a living wage: the soigné hair-styling showcase Coiffure de Paris; the sleazy-sexy rag Paris Magazine; the British upmarket monthly Lilliput (edited by his countryman Stefan Lorant); and finally, after 1937, Harper’s Bazaar. At the same time, during the mid-’30s, he found himself accepted as a member of the avant-garde. He regularly contributed to the tony Surrealist journal, Minotaure, which published his nudes, nature studies, night pictures of Paris, and his Sculptures involontaires (bits of paper unthinkingly rolled, folded, scrunched that he photographed as inscrutable objects.)

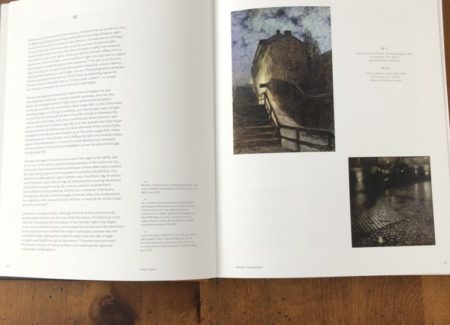

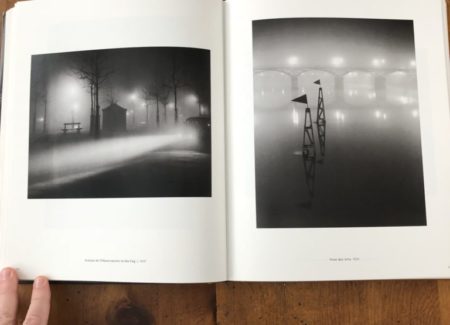

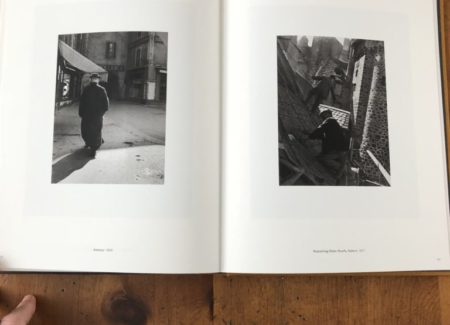

Paris de Nuit was not the first book of nocturnal photographs but it has remained the one against which all others are measured. From watching German expressionist films (most certainly Fritz Lang’s M), he had learned how to exploit the electric glow of streetlamps, neon shop signs, and automobile headlights to sculpt the dark into abstract shapes (cones and trapezoids) that called upon his training as a painter. These pools and ragged edges of seen (or, more often, unseen) illumination created a plush, sinister ambiance for a cast of rough and tumble Paris characters whose enterprises kept them up after polite society had gone to bed.

Many of these scenes, featuring hoodlums and prostitutes, were done with their cooperation, and Brassaï didn’t deny that fact. But he didn’t advertise it at the time either. Being known as someone who knew his way around sinful, secret Paris and was trusted by the underworld economy—and was taking pictures at some personal danger—added to his allure. It was also good for business, as it was for his raffish friend Henry Miller.

Galassi points out that Paris de Nuit was originally published as a tourist keepsake, not an art portfolio, which explains the presence of so many Paris landmarks (Arc de Triomphe, Tour Eiffel, quais along the Seine.) They function like a series of establishing shots for a movie that is always about to begin. Brassaï’s friend, Pierre Mac Orlan—novelist, song writer, pornographer—was his guide to the city’s lower depths, a side of Paris that, as Galassi writes, already had a well-developed mythology going back to the writings of Rétif de la Breton and Baudelaire. The photographs in the book played with and enhanced the glamour of the low life for a bourgeois audience.

Brassaï was, like Atget, not technically a street photographer—at least not as the term was later defined. He did not own a Leica until 1957 when he began to shoot color. His first serious camera, bought in 1929 and thereafter his workhorse instrument, was the medium-format Voigtländer Bergheil, which he mounted on a tripod. (In an early nighttime self-portrait, he stands behind it at a side angle, peering into the view-finder along a snow-smeared boulevard Saint Jacques. Bundled in hat and overcoat, hands in pockets, cigarette jutted out and down, he might as well be drawing a cartoon of himself as a freezing, unhappy, slightly befuddled amateur–someone in a Monsieur Hulot comedy.) In 1935 he added a Rolleiflex to his tool kit.

The book divides his outdoor night pictures (Pleasures I) from those made inside brothels, cafés, bars, dance halls, and backstage at theatres (Pleasures II, III and IV). These indoor situations were often no less fraught and often more cramped for a photographer with a tripod and, thus, probably also staged or at least done with self-conscious subjects.

To balance Brassaï the night owl, Galassi is careful to present his less familiar waking-hour prowlings as well. The pictures in Paris by Day and The Street (I and II) were taken outdoors in sunlight, as were all but one in the section plainly titled Sleep. The well-dressed bourgeois with eyes closed was a motif in Surrealist painting (not only in Magritte) while the sight of indigent men and women sleeping in the streets can be found in several Cartier-Bresson’s photographs from the early ‘30s, rampant homelessness being one of the results of the Great Depression. Brassaï’s contributions to this bleak genre are typically piquant and unsentimental. He had, in Galassi’s words, an “unwavering confidence in the unruly potency of photographic clarity—the blunter, the better…”

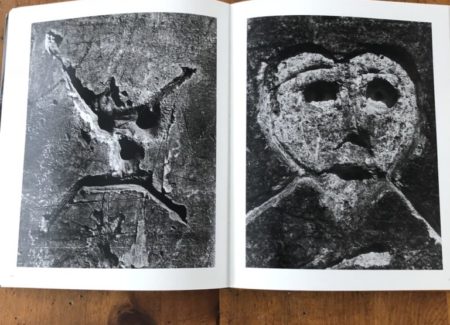

His graffiti pictures from the ‘40s and ‘50s had their own handsome show at the Pompidou in 2016. This smaller selection opens with a poor boy, socks around his ankles, in the act of defacing a wall. (Am I right in suspecting that this delightful scene, too, was staged?) It would be instructive to compare some of these with Helen Levitt’s. The graffiti that she documented was usually drawn, in chalk or crayon, whereas his examples were three-dimensional, carved as well as drawn, aggressively pitted with deep shadows, skulls rather than faces, little Dubuffet sculptures.

Brassaï openly borrowed from other artists (as well as they from him) and his friendships were often mutually beneficial. Picasso entrusted him with photographing his new erotic sculptures in 1943, a hush-hush commission that went on until 1946. It didn’t hurt any artist’s reputation to be associated with the Spanish genius, although Brassaï may have revered him too much. When he finally worked up the nerve to show Picasso his drawings, the painter lavished them with praise and declared that he was wasting his talent on photography. This probably led to Brassaï’s late-in-life worries that he had chosen the wrong career path—an insecurity this show is determined to prove was unfounded.

Deeply conversant in French literature, Brassaï must have seen parallels between his life and successful strivers in the novels of Stendahl, Balzac, Flaubert, and Proust. The rise of this Jewish-Hungarian immigrant through the highest levels of Parisian society was effectuated, as often happened in 19th century fiction, through a liaison with an older woman, in his case an aristocratic woman of immense wealth more than two decades older than he, Mme. Marianne Delaunay-Belleville. They met shortly after he arrived in Paris in 1924 and her connections (and his later sponsorship from Mac Orlan and Picasso) allowed him to move with ease up or down the social ladder.

Galassi has deliberately avoided much biographical information in order to concentrate on the photographs. He is frustratingly sketchy about his subject’s activities during WWII and his political sympathies thereafter. A younger brother disappeared in 1944 “during the war with Russia” (fighting with or against the Nazis?) Brassaï’s personal life is also left a blank. (He did not marry until 1948.) A note on the prints in the show at the back of the catalog mentions that Brassaï eagerly embraced the chance to sell his work when a market for photographs developed in the 1970s. But the essay discretely omits the role played by his widow, Gilbert-Mercédès Boyer, in promoting these later prints on double-weight paper and thwarting curators and collectors from gaining access to his vintage work. (All but seven of the examples chosen by Galassi were printed before 1968.)

Both the show and the essay are mainly focused on the pre-war years, providing lots of new month-by-month gritty details about the magazine industry at the time and numerous local characters, such as Léon-Paul Fargue Le piéton de Paris—the pedestrian of Paris—who guided the photographer around the city’s neighborhoods. The reduced scope of his bounteous investigations, however, means that Galassi has not allowed himself to speculate about Brassaï’s impact on older or younger photographers, other than to note an affinity with Atget—the two met briefly in 1925. Questions of influence are handled more indirectly. It can’t be an accident that the images selected for the chapter The Street share qualities with those of Evans and Winogrand. And having supported, with exhibitions and books, the ambiguous fact-fiction photography of Philip-Lorca diCorcia, Jeff Wall, and Tina Barney, Galassi doesn’t need to connect the dots.

Tod Papageorge has name-checked Brassaï as an inspiration. Larry Clark no doubt felt validated when looking at portraits of illegal behavior and sexual escapades in the ‘30s. In one of her last classes, Diane Arbus credited Brassaï with teaching her that “obscurity” could be as powerful as “clarity.” In Brassaï, as with Brandt, “there is the element of physical darkness, and it’s very thrilling to see darkness again.”

But the contemporary artist-photographer who has emulated Brassaï most openly may be Stan Douglas. His evocations of the naked city in the ‘40s, tableaux of well-dressed gamblers and crooks and dames after hours, in deeply shadowed black-and-white, have sources in post-war Hollywood but also in the ‘30s photographs of Brassaï, which even as they borrowed techniques from cinematic mise-en-scène express their own lingering enchantment as still images.

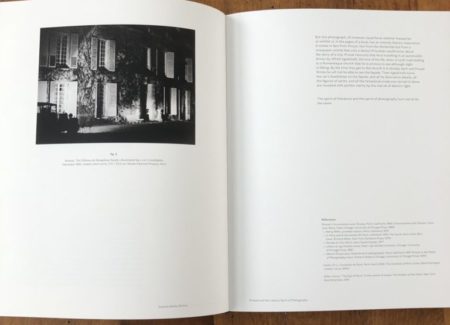

The writer Roger Grenier explained the mysterious timelessness of his friend’s photographs: “The aura of performance (even if the actors, dressed in their own clothes, are playing themselves) and the drama of artificial lighting combine to make some of Brassaï’s nocturnal vignettes look like stills from film noir movies that were yet to be made.”

The roaring commercial engines of the picture magazines that sustained Brassaï and so many other photographers for 50 years was already sputtering by the time of his death in 1984. He became one of the first to be accepted by its replacement, the art market. Perhaps his photographs have never seemed passé because his realism was oddly nostalgic and futuristic at the same time. From the evidence presented here, he has yet to go out of style and maybe never will.

Collector’s POV: No one gallery represents the estate of Brassaï and as a result, his prints are available from many galleries specializing in 20th century European photography. Works by Brassaï are readily available in the secondary markets, with prices generally ranging from roughly $2000 to $60000, with a few vintage outliers in six figures.

Great review, thanks.

Just had a look at how what his camera was like:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ta10clSScXY&t=13s