JTF (just the facts): Published in 2003 by Steidl and the Hasselblad Center, in conjunction with the artist’s receipt of the 2003 Hasselblad Award. 108 pages, including 65 black and white plates. Essays by Gunilla Knape and Manthia Diawara, with a conversation with Sidibé recorded by Andre Magnin. (Cover shot at right.)

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2003 by Steidl and the Hasselblad Center, in conjunction with the artist’s receipt of the 2003 Hasselblad Award. 108 pages, including 65 black and white plates. Essays by Gunilla Knape and Manthia Diawara, with a conversation with Sidibé recorded by Andre Magnin. (Cover shot at right.)

Comments/Context: Malian photographer Malick Sidibé has been on our list of artists to get better acquainted with for quite a while now. We have seen a few of his captivating portraits in group shows or at auction previews over the years, but until now, we hadn’t spent the time to look carefully at the entire body of his work. This monograph is an excellent first resource primer on Sidibé for those who want to educate themselves about this important African photographer.

Sidibé’s

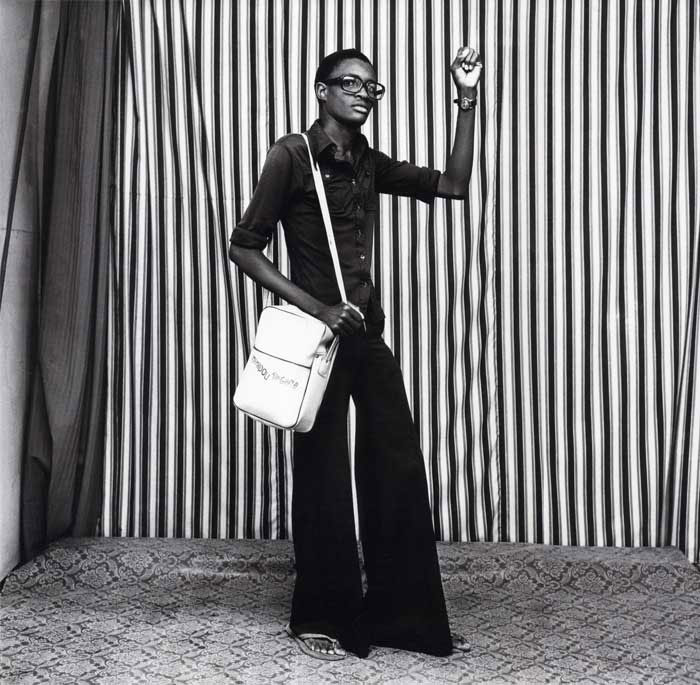

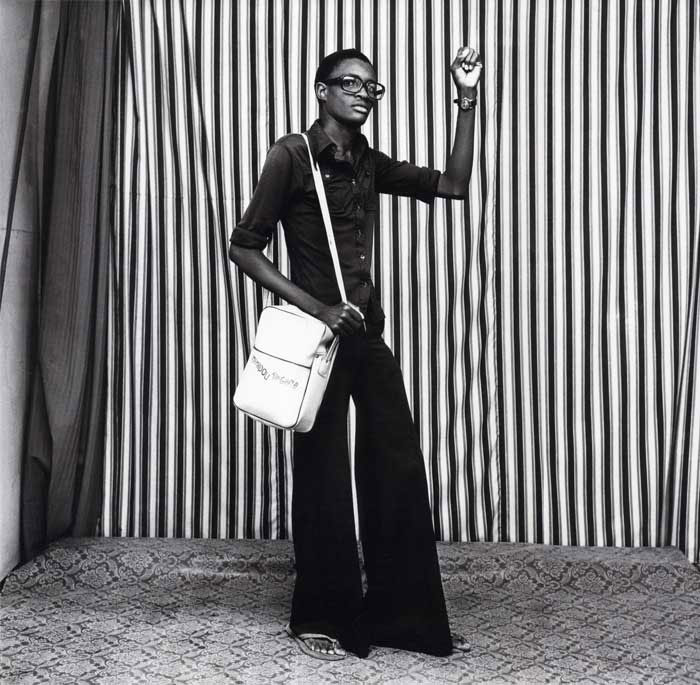

Sidibé’s best pictures come from the 1960s and 1970s, when he made staged studio portraits and looser documentary shots of the youth culture of Bamako. In these post-colonial years, traditional Malian culture was being challenged by the modernizing influences of the West. So while

Sidibé did make many traditional portraits of people in African dress, with elaborate hairstyles and symbolic poses, his images of energetic young people, full of freedom and enthusiasm, have the most interesting stories to tell. (

Young man with bell bottoms, bag, and watch, 1977 at right.)

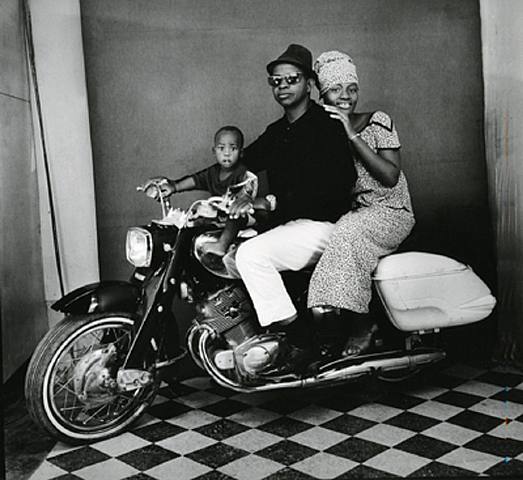

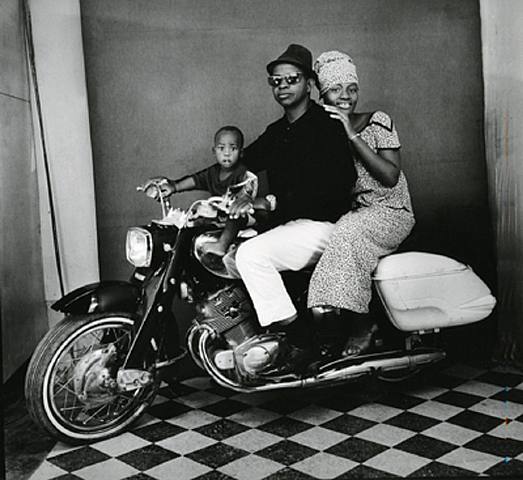

There is an amazing purity and innocence in these pictures. There are kids dressed in their best funky James Brown suits, holding record albums, strutting and showing off. There are crazy sunglasses, big watches, and shiny shoes. There are motorcycles  and scooters brought into the studio, for posing and looking cool. Sidibé let each of his subjects create their own narrative with his many props and objects, and what emerged were pictures full of style and attitude and rock and roll infused pride. One of the things I find most intriguing about these portraits is Sidibé‘s use of clashing patterns, background and floor drops with bold stripes, checks, and polka dots, mixed together with the patterns in his subjects’ clothing. It makes for some high octane visual stimulation. (The whole family on a motorcycle, 1962, at right.)

and scooters brought into the studio, for posing and looking cool. Sidibé let each of his subjects create their own narrative with his many props and objects, and what emerged were pictures full of style and attitude and rock and roll infused pride. One of the things I find most intriguing about these portraits is Sidibé‘s use of clashing patterns, background and floor drops with bold stripes, checks, and polka dots, mixed together with the patterns in his subjects’ clothing. It makes for some high octane visual stimulation. (The whole family on a motorcycle, 1962, at right.)

It is clear that there were some powerful culture and generational conflicts and shifts going on during these times, and the young people were at the center of the revolt.

Sidibé also made some memorable pictures of kids at parties and dance clubs (called

grins), showing off their best moves and imitating their favorite stars. These too have a sense of unabashed happiness; it’s hard not to smile when you see them.

In recent years,

Sidibé has been busy on the awards circuit, picking up the 2003

Hasselblad Award, the Golden Lion for lifetime achievement at the 2007 Venice

Bienniale, and most recently, the 2008

ICP Infinity Award, also for lifetime achievement. All this from an artist who was virtually unknown outside Africa a decade or two ago.

Collector’s POV: If you are a portrait collector,

Sidibé needs to be in your collection. In our opinion, his are images that you will stand the test of time well, without becoming tired.

Virtually all of Sidibé’s photographs that can be found in the secondary market are later prints, made in the late 1990s or early 2000s. These images have been selling in the $2000 to $5000 range at auction, but there haven’t been many in the past five years, so it’s hard to draw much of a pattern from so few data points.

.

Sidibé is represented in New York by Jack

Shainman Gallery, site

here. There was a 2005 solo show there, complete with images surrounded by elaborately painted glass frames.

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2003 by Steidl and the Hasselblad Center, in conjunction with the artist’s receipt of the 2003 Hasselblad Award. 108 pages, including 65 black and white plates. Essays by Gunilla Knape and Manthia Diawara, with a conversation with Sidibé recorded by Andre Magnin. (Cover shot at right.)

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2003 by Steidl and the Hasselblad Center, in conjunction with the artist’s receipt of the 2003 Hasselblad Award. 108 pages, including 65 black and white plates. Essays by Gunilla Knape and Manthia Diawara, with a conversation with Sidibé recorded by Andre Magnin. (Cover shot at right.) Sidibé’s best pictures come from the 1960s and 1970s, when he made staged studio portraits and looser documentary shots of the youth culture of Bamako. In these post-colonial years, traditional Malian culture was being challenged by the modernizing influences of the West. So while Sidibé did make many traditional portraits of people in African dress, with elaborate hairstyles and symbolic poses, his images of energetic young people, full of freedom and enthusiasm, have the most interesting stories to tell. (Young man with bell bottoms, bag, and watch, 1977 at right.)

Sidibé’s best pictures come from the 1960s and 1970s, when he made staged studio portraits and looser documentary shots of the youth culture of Bamako. In these post-colonial years, traditional Malian culture was being challenged by the modernizing influences of the West. So while Sidibé did make many traditional portraits of people in African dress, with elaborate hairstyles and symbolic poses, his images of energetic young people, full of freedom and enthusiasm, have the most interesting stories to tell. (Young man with bell bottoms, bag, and watch, 1977 at right.) and scooters brought into the studio, for posing and looking cool. Sidibé let each of his subjects create their own narrative with his many props and objects, and what emerged were pictures full of style and attitude and rock and roll infused pride. One of the things I find most intriguing about these portraits is Sidibé‘s use of clashing patterns, background and floor drops with bold stripes, checks, and polka dots, mixed together with the patterns in his subjects’ clothing. It makes for some high octane visual stimulation. (The whole family on a motorcycle, 1962, at right.)

and scooters brought into the studio, for posing and looking cool. Sidibé let each of his subjects create their own narrative with his many props and objects, and what emerged were pictures full of style and attitude and rock and roll infused pride. One of the things I find most intriguing about these portraits is Sidibé‘s use of clashing patterns, background and floor drops with bold stripes, checks, and polka dots, mixed together with the patterns in his subjects’ clothing. It makes for some high octane visual stimulation. (The whole family on a motorcycle, 1962, at right.)