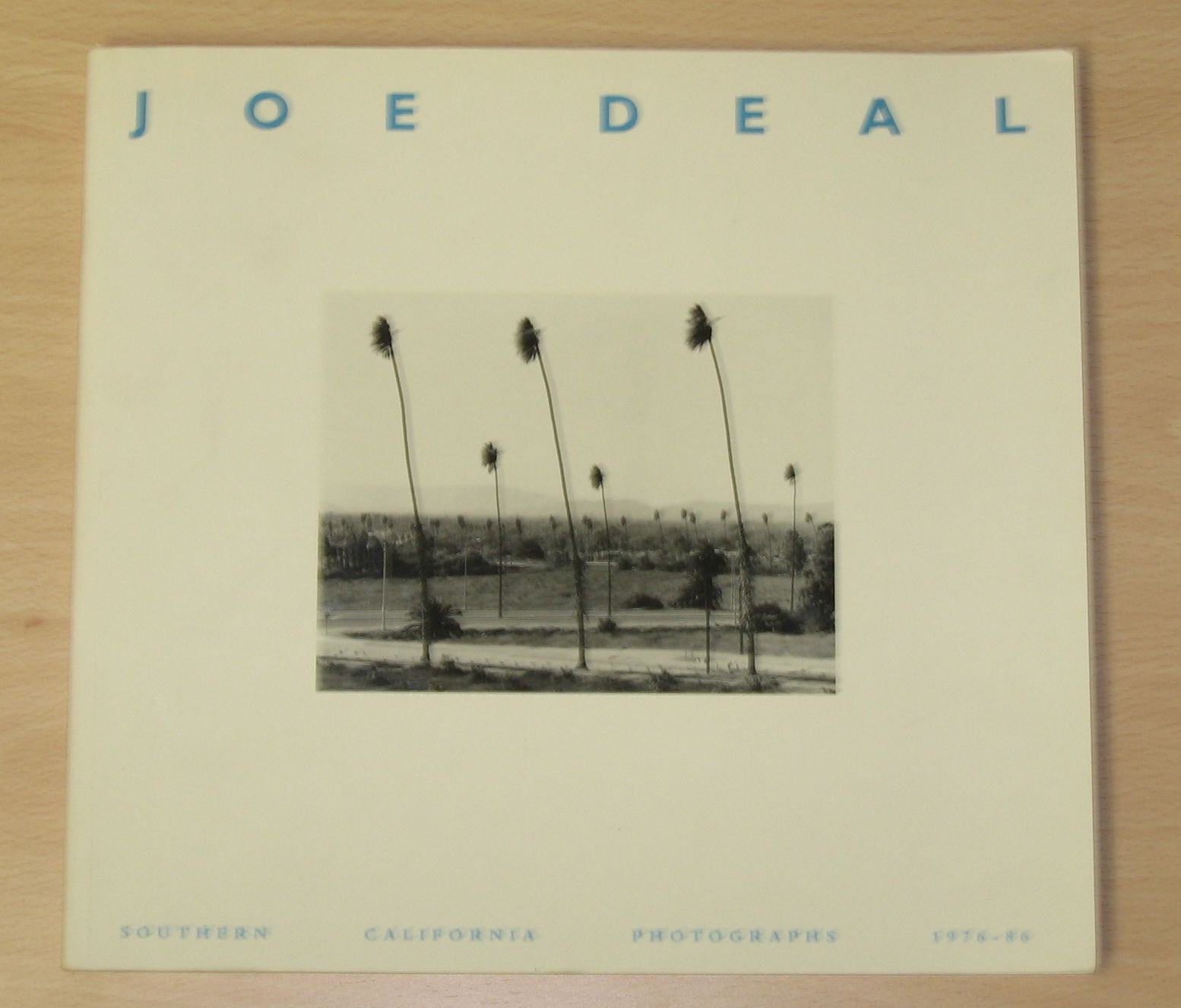

JTF (just the facts): Published in 1992 by the University of New Mexico Press in association with the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. 150 pages, with 68 black and white images. Includes essays by J.B. Jackson, Mark Johnstone and Edward Leffingwell. (Cover shot at right.)

JTF (just the facts): Published in 1992 by the University of New Mexico Press in association with the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. 150 pages, with 68 black and white images. Includes essays by J.B. Jackson, Mark Johnstone and Edward Leffingwell. (Cover shot at right.)

Comments/Context: Joe Deal has been on my hit list for quite a while now. He’s one of those photographers that I felt like I needed to know more about, even though he wasn’t exactly a household name. Deal was of course part of the now landmark New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape exhibit at the George Eastman House in 1975, along with other notable photographers Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, and Stephen Shore. At least for us, of this group, Deal has always been the most elusive; there just seem to be less of his books and prints running around in the circles in which we travel, less discussion of his work in the press and among collectors we know.

I’ve actually been thwarted at least twice in trying to acquire this book; Internet booksellers who thought they had it on the shelf and had it listed in in their database somehow didn’t actually have it when our order came in. Only recently have I successfully got my hands on a copy. I’m happy to report that it was thoroughly worth the wait, and I now feel like I have a much better understanding of why he was included in New Topographics in the first place, and how his perspective is distinct from the others who also took on the subject matter of suburbanization at that time.

In my view, Deal’s images are mostly about the process of human settlement, about the underlying land and how we have built our lives upon it. They chronicle our occupation of the land, the tensions between the land and our chosen way of life, and the process of socialization and division that we impose upon our cities and communities as we create them. What I found most surprising in seeing a larger group of his work together in book form is that his viewpoint seems much less ominous and scolding than Baltz or Adams; his focus on the instabilities or ironies of our lives is subtler, perhaps bit less obviously judgmental.

The book is divided into three sections: The Natural Environment, The City, and The City’s Edge, with work from several different projects getting rolled up under each of the headings. The images from The Natural Environment are primarily of the unique geography of Southern California: rocky hillsides, scrub brush, sand, wild scraggly trees and tangled bushes. In most of the pictures, an intrusion in the form of a dirt road or other human presence in the distance disturbs the otherwise pristine view of the untamed wilderness; we’re clearly encroaching on the natural environment, and doing it in a way that detracts from its rugged beauty.

If there is any nature at all in the images in the section entitled The City, it was likely put there by someone. There are images of downtown construction projects, as well as of beach communities. There is a terrific sequence of images in this group that brings home the nature of our relationship to the natural world: a concrete patio overlooking the ocean, followed by synchronized swimmers in a suburban pool, followed by a lone man lying on the beach in the blinding sun, followed by families watching the twisting plastic forms of water slides, followed by trailers parked edge to edge along the coastline. The land has been domesticated for our entertainment and recreation (or so it seems).

The most powerful of the images in this book are the ones in The City’s Edge. Here Deal has focused on single family suburban homes (and their occupants), built in planned communities and neighborhoods, backing up to the bone dry desert. Often the images peer into deserted back yards, where the formal perfection of the front yard is gone, where sun beaten lawn furniture, abandoned toys and trash cans take center stage. At one level, there is an amazing futility in these pictures, a ridiculousness found in watering a patch of lawn under the punishing sun, or sitting on a chaise amidst the dirt. And yet, the kids are flying a kite or playing happily in a plastic pool in the driveway, and there is some sense that these people have found a degree of happiness in having a place of their own, even if it is in this inhospitable and likely unsustainable environment.

This is what I mean about how Deal has approached his subjects. These suburban tract homes were an easy target; it would have been relatively straightforward to make them look ugly (and he does this to some extent). Deal has however found a way to make the point about the inherent problems with this kind of development, and the need to build communities that are in better balance with their natural environment, but he’s done so without the overt harshness and lecturing that turns people away. He’s left in some of the optimism that got us into trouble in the first place; the feeling that we can remake this world into a place that fulfills our dreams. He’s just pulled back the curtain to remind us that this new life, on this stange land, is not turning out quite how we had envisioned.

This is a fine monograph of an often overlooked photographer, well worth adding to your library.

Collector’s POV: Joe Deal is represented by Robert Mann Gallery in New York (here). Very few prints by Deal have found there way into the secondary markets in recent years; those that have come up for sale have ranged in price between $1000 and $4000.

Transit Hub:

I tracked this book down through the library after reading your review and wanted to say thanks. An underrated gem for those interested in the New Topographics. Was really struck by the tension created by the elevated camera position in a lot of the images.