JTF (just the facts): A total of 68 works in various media, displayed against white walls in a series of four connecting gallery spaces. 35 of the works are photographs or studies that include photographs, alternately made of gelatin silver prints, chromogenic prints, and cibachrome prints between 1969 and 1978 (some printed in 2014/2015). In addition to the photographs on view, the show includes collages, watercolors, drawings, sculptural installations, maquettes/studies, photocopies, performance ephemera, and other objects. While the photographic maquettes, studies, and documents that incorporate handwritten text are clearly unique, most of the other photographs are available in editions of 2+1AP or 3+1AP. A small catalog of the show is available from the gallery for $20. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: A visit to Bill Beckley’s show of early work (from the late 1960s and 1970s) feels exactly like time travel. A step into the gallery is like a flash trip back to a very specific artistic moment, to the exact fulcrum point when Minimalism and Conceptual Art were being challenged, expanded, and pushed further into performance, installation, and photography, but really before the arrival of the media-incisiveness of the Pictures Generation. With the benefit of hindsight and the knowledge of what actually came later, it’s possible to look back at Beckley’s ideas and contributions with remarkably fresh eyes, and to see both his hits and misses against the longer sweep of art history.

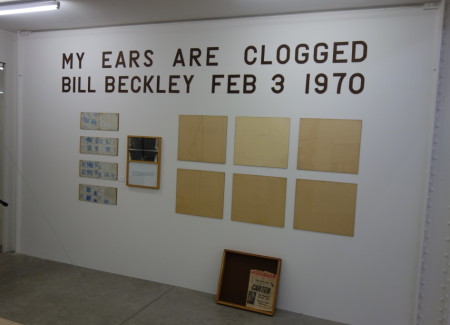

Many of the earliest pieces on view here feel like a direct reaction to the hermetically sealed austerity of Minimalism. There’s a looser playfulness to be found in Beckley’s silent ping pong table (covered with sound deadening foam), his live rooster caged above a plywood bed, and his songs to be performed while doing a chin-up and sliding down a playground slide. Turtles, popsicles, a trained raven (who says the word “dark” in reference to a Bruce Nauman work), and swings to be mounted on the Brooklyn Bridge all make appearances, combining irreverence, cleverness, and chance in equal measure.

What’s fascinating is that Beckley’s photographs from this period are both infused with a rigorous conceptual thinking and generally uninterested in photography-specific issues – they are not photoconceptualism in the manner of early Wegman, Baldessari, Bochner, or Oppenheim. In general, they aren’t interrogating the medium of photography and its visual/optical limitations and quirks, but instead veer off into an investigation of elliptical image-based storytelling. Starting in the early 1970s, Beckley began to combine black and white images and long stretches of hand written (often nearly illegible) text, perhaps leveraging the aesthetic of Allen Ginsberg’s caption heavy pictures. But Beckley’s works went somewhere else – they weren’t about text that supported or explained the images, it was the other way around; the text was the central narrative point and the images provided intermediate moments where a specific thing or person became boldly visual.

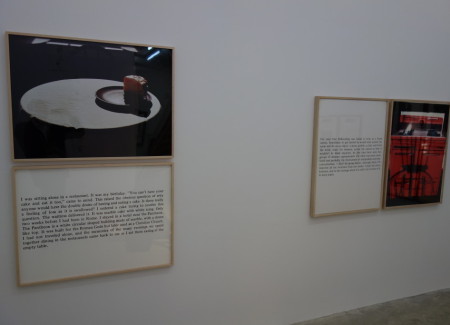

Soon Beckley had transitioned to cibachrome, moved to typed text instead of hand written vignettes, and increased the scale of his works, and it’s these larger, wall-filling compositions from the next few years that are the most exciting in the show; for those contemporary photographers trying to map new methods of storytelling, they will be nothing short of revelatory. Single image works like Cake Story (1973) and De Kooning’s Stove (1974) use a single picture to illustrate meandering thoughts that don’t exactly go anywhere. Cake Story mixes a birthday, a mediation on the “have your cake and eat it too” saying, and the circular form of the Pantheon, while De Kooning’s Stove glances off the issues of Abstract Expressionism and De Kooning’s own artistic process before returning to the warmth of the oven itself, seen in a glowing red light.

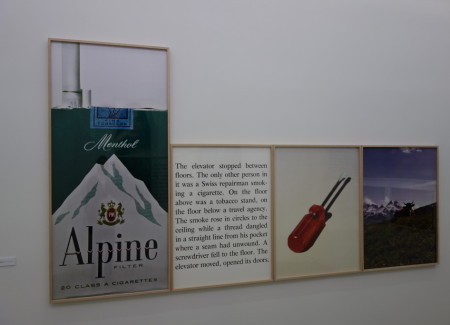

By 1974, Beckley had moved on to multi-image constructions, and these forms gave him more freedom to expand his indirect storytelling possibilities. Elevator (1974) tells a short wandering tale of a Swiss elevator repairman, who smokes and has a hole in his pocket; a pack of cigarettes, the offending fallen screwdriver, and a Swiss landscape with a cow bookend the paragraph of text, expanding the narrative here and there. Bus (1976) does something similar, with a lipstick, a second story window, and (you guessed it) a bus providing the anchor points for an ephemeral disconnected story. In both cases, there is no conclusion or neatly tied up ending, but a looser more open feeling, where ideas (and images) flit in and out without entirely registering in a rigorous linear manner. Deirdre’s Lip (1978) is even less narratively conclusive – it combines snatched words from a conversation in a phonebooth with cold breath vapors and a train whistle, creating a kind of stream of consciousness description that connects a series of closely observed (almost interior) details. Beckley’s works aren’t as oblique as some of Rauschenberg’s rebus-style gatherings of images, but they share a similar internal structure, where images balance off each other to generate more complex ideas and references.

Beckley’s image-only works trade narrative uncertainty for a more pared-down graphic aesthetic. A rabbit and turtle jostle for position along the top edge of the wall, footsteps climb upward until they are interrupted by a banana peel, and a triptych of faucet, droplet, and bucket of water creates a step-by-step relationship between separate objects. Two other triptychs riff on Barnett Newman, turning his muscular zips into a thorny rose stem, a spindly violet stem, and a thin train of sugar on fields of bright red, blue, and yellow, and a pair of faucets and a single drain on the same three color fields; they’re a smart conceptual twist on the well known color study, bringing references to natural forms, tastes, and temperatures (hot and cold) back into what was previously a strictly color-only dialogue.

The key innovation to be found in Beckley’s early work, and one that could easily rediscovered today, is that photographic time need not be serial or sequential to drive a narrative. While Duane Michals and Paul Graham have successfully used multiple cinematic frames to pull a photographic vignette along, Beckley puts the onus on the text to control the pace. In the context of his short stories, the images all occur at the same time, collapsing the time experience into a woven built-on-itself package. This makes for something decidedly non-cinematic, more abstract and networked in the distributed architecture of its connections. If the images chosen were less literal and less tied directly to words in the text, such an approach might open up even further, allowing for thoughtful tangents, references, and dead ends. There’s a spark of something exciting for text-centric photographic storytelling that got buried here some forty years ago; I hope that a new generation of photographers find this show and this work, and can pick up where Beckley left off.

Collector’s POV: While most of the photographic maquettes, studies and documents in this show are not for sale, a few of the larger photographic works are available, ranging in price from roughly $40000 to $60000. Beckley’s work has little consistent secondary market history, and given that many of these works haven’t been shown for decades, gallery retail likely remains the best/only option for those collectors interested in following up.