JTF (just the facts): A total of 8 large-scale color photographs, framed in blond wood and matted, and hung against white walls in the two room gallery space. All of the works are c-prints, made between 2003 and 2014. The images are digital composites, with some put together within a few months, others over several years. Physical sizes range from roughly 28×41 to 51×118, and the prints are available in editions of 5. A 46-page catalog of the exhibition (with essays by Leon Wieseltier, Ileana Selejan, and Sharon Rotbard) has been published by the gallery in an edition of 1000. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: For 15 years, Barry Frydlender has expanded the boundaries of what Paul Graham, disparagingly, calls the tradition of “the great photograph.”

It’s a lineage that goes back to F. Holland Day and Ansel Adams, and that now includes Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall, and Gregory Crewdson, artists with disparate aesthetic programs but united by a willingness to devote days or years to the pre-production and/or post-production of what they envisioned would be jaw-dropping, epiphanic images.

Opposed to this way of working, in Graham’s nomenclature, are those like himself and Walker Evans, Robert Adams, and countless others who have believed that their energy—and the medium—was better invested in capturing a series of less majestic images, the sum of which may or may not add up to a revelation.

Frydlender has succeeded on more than a few occasions in realizing his ambition. Asked to nominate some of the most accomplished photographs produced in this century, I would put The Flood (2003), Raid (2003), and Blessing (2005) near the top of the list, with Waiting (2005) and Eagle Rock (2011) not far below.

Many photographers in the last 30 years have made panoramic prints worthy of their exorbitant cost and immense scale; and many more photographers have taken pictures that registered the social-political-historical tensions of our time. Frydlender is one of a handful to have done both.

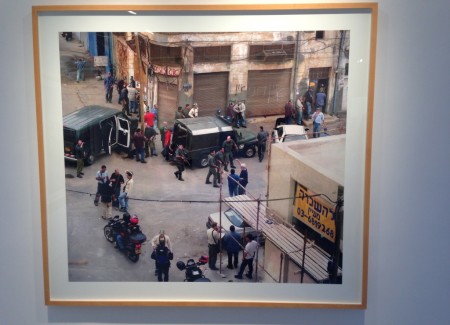

Patiently knitting together with digital tools as many as 75 different views of the same scene taken over many weeks and months, or even several years, he has created images that are as densely populated with figures as a Tintoretto and that call into question the application of concepts such as “transitory” or “moment,” once basic to the language of photography. What Beate Gutschöw’s digital sleight-of-hand has done to complacent ideas about pastoral landscape, Frydlender’s multiple exposures have done to what we think of as the urban street.

His latest show reprises some greatest hits (The Flood and Raid were in his 2006-07 mid-career retrospective at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and MoMA) and adds another twist to the question of what is documentary photography. Of the 8 images here, 7 of them depict the same scene—the view looking out at the skyline and down at the street from the windows of his Tel Aviv apartment—over 16 years.

One interpretation of this domestic, autobiographic sequence is that Frydlender wants us to witness the pace of gentrification that has transformed his neighborhood. The shabby concrete building across the street from him, first seen in Composite Horizon (180 Degrees) and photographed in analog in 1998, had not changed much in 2003, the dates of Raid and The Flood, even if the going on behind and to the side of this central structure are in considerable flux from one picture to the next.

But by 2011-2013, young people have moved into the building’s upper floors: a rock band can be seen playing in the windows of Rehearsal. Finally, by 2014, in Noach, the view is prosperous and sanitized: the grim unpainted gray facade of the corner structure is now a white, Bauhaus-styled unit of condos, complete with a glassed-in penthouse, young families on the terraces, trees on the street, and a dark-skinned gardener to water them. Armed soldiers and the fear of more war and rainy skies have in a decade been replaced by air-conditioned interiors and people walking their dogs in the Mediterranean sunshine.

One of the uncanny aspects of Frydlender’s work is his ability to keep faith with certain notions of “straight” photography and yet complicate, bend, or entirely undermine it. Many artists before him—Roy DeCarava and William Gedney to name only two—have photographed the quotidian events that happened over weeks or months outside their homes. The sociologist Camilo José Vergara has returned with his camera to many of the same blocks and vantage points in American inner cities, from Detroit to Harlem, to catalog what has and has not been altered by urban growth, decay, economic initiatives or the lack thereof over decades.

What constitutes change or truth in Frydlender’s scenes, however, is hard to determine because nothing in his photographs can reliably be said to have happened in the same instant. He moves figures around the frame and changes the times when they were in identifiable locations, thus destroying one of the foundational aspects of photography that William Henry Fox Talbot so enjoyed about his invention: its power to describe an array of objects honestly and simultaneously.

As he famously wrote as a caption for his photograph “Articles of China” in The Pencil of Nature: ” From the specimen here given it is sufficiently manifest, that the whole cabinet of a Virtuoso and collector of old China might be depicted on paper in little more time than it would take him to make a written inventory describing it in the usual way. The more strange and fantastic the forms of his old teapots, the more advantage in having their pictures given instead of their descriptions.

“And should a thief afterwards purloin the treasures—if the mute testimony of the picture were to be produced against him in court—it would certainly be evidence of a novel kind; but what the judge and jury might say to it, is a matter which I leave to the speculation of those who possess legal acumen.

“The articles represented on this plate are numerous: but, however numerous the objects, however complicated the arrangement, the Camera depicts them all at once.”

This is the exact opposite of what happens in Frydlender’s process of picture-making.

Remarkably, despite these transgressions, his images retain many of the traditional pleasures of photography as Talbot originally conceived it. Warping time to suit his own pictorial ambition has not prevented him from trying to seamlessly stitch together the scraps into a convincing whole. He does not want to quash the viewer’s curiosity about the swarming abundance of detail, or to dispel the belief that everything depicted is somehow “real.” The absence of a strong dramatic center that could be quickly understood encourages this more leisurely reading.

Not every picture here is as riveting as The Flood or Raid. Glimmer (an overhead view of a gleaming tin can on a rain-streaked sidewalk beside a parked car) strains to imitate Wall, who often enlarges a banal object or or anecdotal gesture into a moment of numinous conflict.

The post-1967 history and daily life in Israel offers him plenty of that already. Those of us who don’t know Tel Aviv or cannot read Hebrew are no doubt missing layers of political meanings in these images. Sharon Rotbard’s catalog essay provides helpful background about the history of the terrain in the photographs. Visible from Frydlender’s apartment is one of the four roads that have connected Tel Aviv with the rest of the country. The apartment towers that have sprung up on the skyline in Cranes and Falling Bricks are recent and signs of the booming economy. They are also widely hated, according to Rotbard, the equivalent of more Trump dumps.

The photographs chronicle the devouring of the ancient port city of Yaffo (Jaffa) by Tel Aviv, a development that Frydlender has charted through the white-washing and modernizing of the former concrete Palestinian apartment on his corner. Even the Israeli Defense Forces Museum, so prominent in Raid and The Flood but crowded out in the post-2010 photographs , is no match for the clout of Israeli Yuppies.

Courbet, in his panoramic canvases of 1849-50, “Burial at Ornans” and “The Stone Breakers,” infused painting with grandiosity and a down-to-earth realism. At his best Frydlender achieves this same difficult fusion, avoiding the obsequious ironies of Gursky and the Hollywood schmaltz of Crewdson.

Only a few of Frydlender’s images in the past were built around colors (Israeli hotel swimming pools) or settings (European cafes) that might be called pre-possessing. For whatever reason, those are among his least compelling efforts. When his palette is restricted to the duns of sand and concrete and mud, the results are usually happier. This new show may not be entirely new, but it is gratifying to see that he remains engaged with the struggle to fashion durable pictures out of the plain, often ugly stuff outside his front door.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced between $15000 and $60000, generally based on size, with two (Raid and The Flood) already sold out. Frydlender’s prints have an intermittent secondary market history, with just a handful lots coming up for sale over the past few years. Prices for these works have ranged between roughly $38000 and $111000.

Solid show and a wonderful artist, but I disagree, in light of other artists reviewed on this site, on the three-star rating.