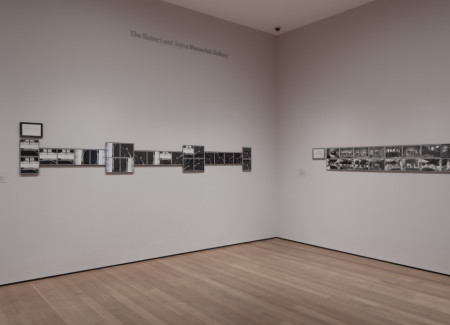

JTF (just the facts): A total of 345 black and white photographs, framed in black and unmatted, and hung against grey and red walls in the two room divided gallery space. The exhibit was organized by Lucy Gallun. The prints were acquired in 2013 as part of a larger donation from the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation.

While all of the photographs on view were made by Shunk-Kender, the images have typically been attributed to the artist whose work/performace was being documented. As such, the following artists have been included in the show, with the number of prints on view and their dates as background:

- Yves Klein: 5 gelatin silver prints, 1960, 1 newspaper, 1960

- Yayoi Kusama (Mirror Performance): 20 gelatin silver prints, 1968

- Yayoi Kusama: (The Anatomic Explosion, New York): 20 gelatin silver prints, 1968

- John Baldessari: 4 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Richard Serra: 22 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Dan Graham: 20 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Wolfgang Stoerchle: 15 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Bill Beckley: 12 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Lee Jaffe: 21 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Vito Acconci: 16 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Mario Merz: 21 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- George Trakas: 7 gelatin silver prints on board, 1971

- Richards Jarden: 9 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Mel Bochner: 8 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Gordon Matta-Clark: 18 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- David Askevold: 7 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Robert Morris: 10 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Douglas Heubler: 14 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- William Wegman: 12 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Allen Ruppersberg: 16 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Michael Snow: 25 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Keith Sonnier: 17 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Jan Dibbets: 25 gelatin silver prints, 1971

- Laurence Weiner: 1 gelatin silver print, 1971

(Installation shots below. Photos by John Wronn. ©The Museum of Modern Art, New York.)

Comments/Context: For the vast majority of visitors to this photography exhibit, the names of Harry Shunk and János Kender will be a complete mystery, a pair of unknowns to be discovered for the first time. In the galleries, these visitors will find sequential documentary images of performances and happenings from the 1960s and 1970s, visual evidence of ephemeral artworks made by some of the period’s most important, influential, and innovative artists, from Gordon Matta-Clark and John Baldessari to Dan Graham and Richard Serra. By their very nature, these artworks disappeared immediately, leaving the photographs as the only tangible memories of what happened. Seeing them again transports us back to those times and allows us to vicariously participate in these conceptual stunts, antiwar protests, physical disturbances, and avant-garde group actions, recreating moments and artistic ideas that long ago vanished into thin air. If we want to read these pictures simply as proof of what happened then, then the show delivers a well edited sampler from that busy artistic time.

But if we dig a little deeper, the Shunk-Kender exhibit poses a more complicated set of definitional conundrums and dilemmas for thinking about photography as an artistic medium. When a photographer documents performance art is he or she merely capturing it mechanically or adding an inherent layer of interpretation? Are the pictures “made” by the performance artist or the photographer? And do we change our answer if there is overt communication and/or collaboration between the two? What happens when we extend this thinking to changeable Earth/land art, or any of the performing arts for that matter, particularly dance? Where does the photographer’s input fit in these areas? What credit does he or she deserve?

Part of the reason Shunk and Kender are largely unknown is that our answers to these and other related questions have often come down on the side of the performance artist rather than the photographer who helped save the performance for posterity – we have typically seen images of performances as documents of the creativity of the performance artist rather than that of the photographer. And so even though Shunk-Kender were intimately involved with Yves Klein’s famous Leap into the Void, taking multiple source images and helping to create the now iconic swan dive into the street montage, it is Klein who is primarily remembered for the surreal and terrifying picture. It is his imaginative genius we generally celebrate, not Shunk-Kender’s.

So if we agree that those that execute Sol LeWitt’s painstakingly intricate wall drawings are not the important artists, what are we to conclude about Shunk-Kender and their contributions to these kinds of performances? Yayoi Kusama’s Mirror Performance would have undeniably looked better/worse/different if it had been captured by less talented photographers. When her glow-in-the-dark spots on nude bodies are reflected and refracted, turned into blurred disco ball wisps of light, was that her idea, or the inspiration of Shunk-Kender, like Brancusi using light to rethink his sculptures? In this case, was photography primary or meta or both?

This bright line gets even more muddy in many of the 1971 performances that took place on the rotting Pier 18. We might agree that the images of William Wegman setting up bowling pins and rolling a ball into the river, or those of Allen Ruppersberg putting a brick from Houdini’s home in a chained and padlocked suitcase and flinging it into the water are really mostly about the performances and not particularly about the vision of the photographers. But what of Mario Merz’ instructions to take a series of “picturesque” pictures, or Mel Bochner’s rules requiring images at exact measurements along the pier, or Jan Dibbets’ directions to take a gradient of vistas at various f-stops, or Douglas Huebler’s notes to pick the “best” aesthetic spots on the pier and then make shots and mark those locations? In each of these cases, Shunk-Kender had quite a bit of leeway in how they would interpret their tasks, and their decisions and participation were integral to the performance itself.

So while it is certainly possible to enjoy this show simply for the historical thrill of seeing Vito Acconci wandering around blindfolded or Robert Morris lining up people for an equinox sunset, its subtly perplexing questions about the involved or arms length role of photography are equally thought provoking. Once you start to pull on the “photographer interpreting the performance” string, the whole ball unravels, leaving a satisfyingly complex mess to puzzle through.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. In addition, collectors will likely need to search for Shunk-Kender’s work under the names of the various documented artists, as images of Yves Klein’s Leap into the Void for example will almost certainly have been listed/offered under Klein not Shunk-Kender.