JTF (just the facts): A total of 35 color photographs, presented on fawn-colored mats in silver-finished wooden frames, and hung against white walls in the first three rooms of the gallery. Thirty of the 35 are dye diffusion transfer prints (Polaroids), four are dye transfer prints, and one is a C-print. Sizes vary from 3 ¼ x 4 ¼ inches to 11 ½ x 14 ¼ inches. Two-thirds of the works date to the early-mid-1960s while the remainder were made in the 1980s, with two anomalies from the 1970s. All are vintage except for the C-print. A catalog of the exhibit, with an essay by Lisa Hostetler, is available from the gallery. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Among the first artists invited by Edwin Land to experiment with Polaroid’s color “instant” film in the early 1960s, Marie Cosindas had a jump start on her contemporaries. A 1966 solo show at MoMA and a 1978 monograph (with an effusive introduction by Tom Wolfe) ought to have guaranteed her a lifetime of visibility and success.

It was not to be. As color photography became the norm, and a younger generation embraced hard-edged documentary and then brain-teasing conceptualism, she and her indoor still-lifes of dolls and flowers looked increasingly musty and behind the beat. She has popped up in recent group histories, “The Polaroid Years: Instant Photography and Experimentation” and “Color Rush: American Color Photography from Stieglitz to Sherman.” But with a career that began in the ‘60s, she did not qualify for inclusion in retrospectives about ‘70s color. The 1978 monograph is seldom mentioned in histories of the photobook.

Her appearance at Silverstein marks a reengagement with the New York art world after being MIA for almost 30 years. Solo exhibitions in 2004 and 2008 at the Robert Klein Gallery in Boston (her home) and last year’s “Marie Cosindas: Instant Color” at the Amon Carter Museum have pushed this process along.

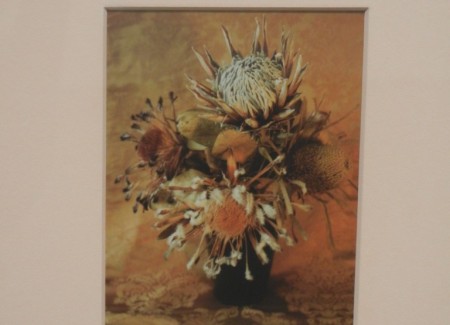

Those who have never seen a solo show of her early Polaroids will be amazed by their size, many of them no bigger than a daguerreotype. Actual prints by most artists are larger than their reproductions in books, newspapers, and magazines; Cosindas’s work might be an exception. Small prints demand more attention from the viewer than gigantic ones, and the dark, bejeweled hues and dense patterns of her compositions accentuate this trait. The rows of pictures around the four walls in the second room at Silverstein could be mistaken for Amazon butterfly specimens.

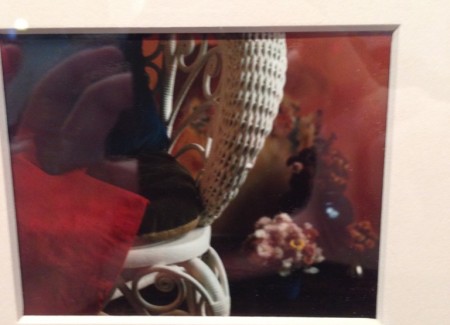

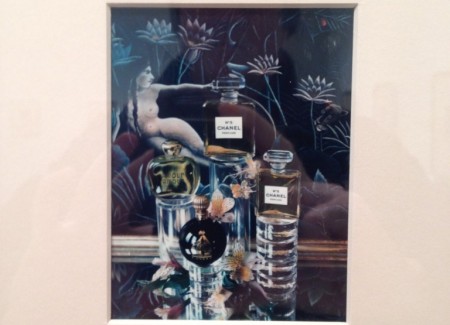

Before studying photography with Ansel Adams, Cosindas trained as a painter, a background reflected in the firm control she maintains over her subject matter and her preference for studio settings. Apart from a few portraits here—none of them entirely successful—this show consists of vanitas still-lifes on tabletops: flowers, vegetables, stuffed game birds, metal urns, porcelain figurines, strings of pearls,and mirrors in silver frames. Some of these pictures were exhibited in 1966 at MoMA. There are also photographs of old-time commercial signs from the corporate archives of Anheuser-Busch and Wrigley’s, and two studies of perfume bottles.

Cosindas’s color is soft and buttery. The light is never harsh. The dusky dimness, combined with the smaller-than-life-size renderings of the objects, pulls us deeper into her world, which promises the sharing of intimacies.

At first, viewers wanted to hear what these revelations might be. She burst upon the scene as movies (“Bonnie and Clyde”) and fashion (Edwardian hippie dress) were turning the clock back. But the same amber ironies that earned the young Cosindas praise from those who never thought color photography would do anything except record vacations and advertize soft drinks worked against her as color photographers took to the streets. Their pictures made the things of this world seem more exciting and irregular than anyone had imagined while hers contracted them into an attic of mementoes wrapped in tissue paper.

Unlike other photographers who applied a painterly eye to photography—notably Jan Groover and Barbara Kasten—Cosindas devised pictorial space as if Cézanne and Cubism had never happened. The last work in the show is a still-life of roses in a vase next to a photograph of the actor William Powell in an Arts & Crafts frame. Like so much of Cosindas—too much—the image summons up a past of fine manners and leisurely decadence filtered through a sepia-tinted haze.

Younger artists can learn a lot from this show, starting with the forgotten virtues of small scale. Pictures ten times the size of Cosindas’s don’t have as many layers of color and texture. For that alone, her place in photographic history is secure. With so many museums and galleries re-examining the pioneers of color photography, can a revival of Ernst Haas and Sheila Metzner be far behind?

Collector’s POV: None of the Polaroids in this show are for sale individually. According to the gallery, if she were to sell them, a buyer would have to purchase them as a group and keep them intact. The dye transfers are for sale between $20000 and $30000. Cosindas’s work has very little secondary market history in the past decade. As such, gallery retail is likely the only viable option for those collectors interested in following up.