JTF (just the facts): A group show consisting of the work of roughly 90 artists, photographers, and space agencies, variously framed and matted, and hung in a series of rooms on both sides of the second floor hallway. The exhibit was organized by Mia Fineman and Beth Saunders.

The following artists/photographers have been included in the show, as arranged by thematic section:

Mapping the Moon

- Galileo Galilei: 1 engraving, 1610

- Francesco Fontana: 1 engraving, 1646

- Claude Mellan: 3 engravings, 1635

- Johannes Hevelius: 1 engraving, 1647

- John Russell: 1 graphite drawing, 1794

- Charles F. Blunt: 1 lithograph, 1842

- John William Draper: 1 daguerreotype, 1840s

- Gustavus W. Pach: 1 albumen silver print, c1880

- Samuel Dwight Humphrey: 1 daguerreotype, 1849

- Antoine-Francois-Jean Claudet: 1 daguerreotype, 1846-1852

- John Adams Whipple: 2 daguerreotypes, 1851, 1852, 4 salted paper prints from glass negative, 1857-1860

- Henry Draper: 1 albumen silver print, 1863

- Warren De La Rue: 1 albumen silver print, c1856, 1 set of albumen silver transparencies on glass, c1858

- Austin Augustus Turner: 12 albumen silver prints, 1863

- William Henry Fox Talbot: 1 photoglythic engraving, c1864

- Lewis Morris Rutherfurd: 1 albumen silver prints, stereographs, 1865, 1870s

- Camille Flammarion: 1 albumen silver print, 1867

- James Nasmyth: 1 woodburytype, 1885, 1 heliotype, 1874

- John Brett: 1 black chalk heightened with gouache, 1884

- Etienne Leopold Trouvelot: 1 ink, gouache, and graphite, 1872-1873, 2 chromolithographs, 1882

- William Langenheim: 7 daguerreotypes, 1854

- H.A. Lawrence: 1 gelatin silver print, 1883

- Paul Henry: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, 1890

- George W. Ritchey: 2 gelatin silver prints, early 20th century, c1901

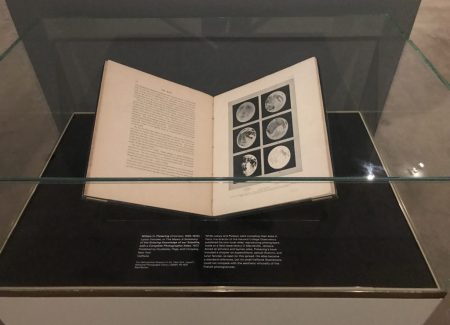

- William H. Pickering: 1 halftone print, 1903

- Lick Observatory: 1 gelatin silver transparency on glass, c1896, albumen silver prints/stereographs, 1902

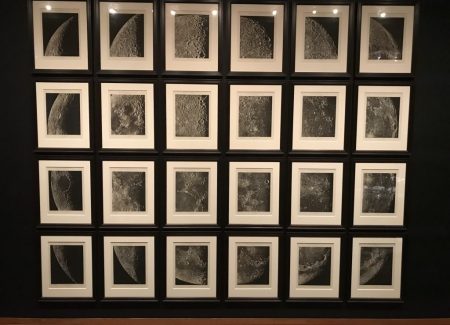

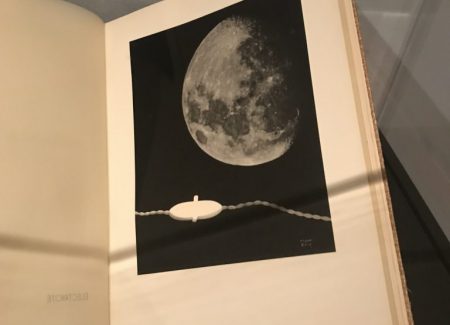

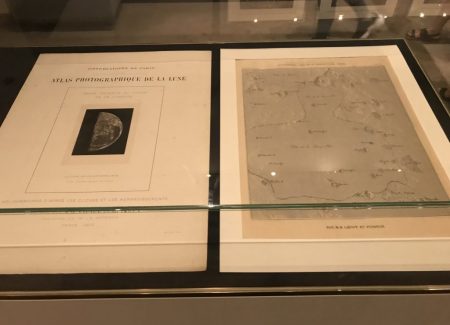

- Maurice Loewy: 83 photogravures, 1896-1910

- Charles Le Morvan: 48 photogravures, 1914

- Four-inch refracting telescope, c1800

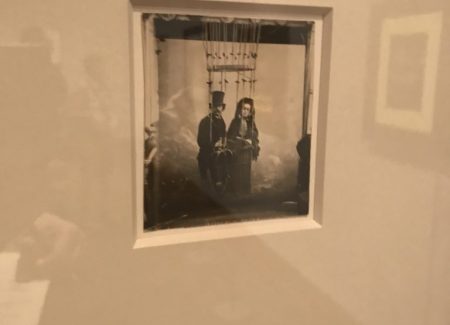

Daydreams by Moonlight

- Filippo Morhern: 1 etching and aquatint, 1766-67

- Leopoldo Galluzzo: 1 lithograph with applied color, c1836

- Gustave Doré: 1 engraving, 1862

- Man Ray: 1 photogravure, 1931

- Caspar David Friedrich: 1 oil on canvas, c1825-30

- Thomas Rowlandson: 1 aquatint with applied color, 1799

- Carlo Naya: 1 albumen silver print from glass negative, c1875

- Edward Steichen: 1 platinum print with applied color, 1904

- Georges Méliès: 4 ink or ink and gouache prints, 1902/1930, 1 digital video transferred from 35mm. film, 1902

- Bliss Brothers Studio: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1901

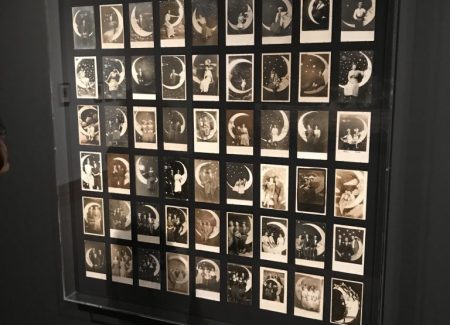

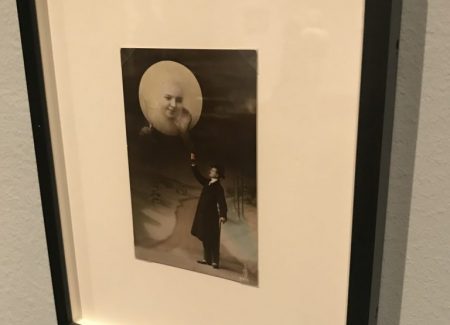

- Man in the Moon postcards: 68 gelatin silver prints and chromolithographs, 1900s-1940s

- Emile-Antoine Bayard: rotogravures, 1872

- Nadar: 1 gelatin silver print from glass negative, c1865/1890s

- Otto Hunte: 1 ink and gouache, 1929

- Fritz Lang: 1 digital video transferred from 35 mm. film, 1929

- Irving Pichel: 1 digital video transferred from 35 mm. film, 1950

- Chesley Bonesteil: 1 acrylic over photomontage, 1957

Moonshot

- Vasily Baturin: 1 album of 117 gelatin silver prints, 1969

- TASS: 1 gelatin silver print, 1959

- Aerojet-General Corporation: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1962

- Ralph Turner: 1 epoxy, 1966

- NASA Surveyor 6: instant black-and-white prints, 1967

- NASA Lunar Orbiter 2: 1 gelatin silver print, 1966

- NASA Lunar Orbiter 3: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1967

- NASA Lunar Orbiter 4: 1 gelatin silver print, 1967

- NASA Lunar Orbiter 5: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1967

- William Anders: 1 color laser print, 1968

- Harrison Schmitt: 1 color laser print, 1972

- James McDivitt: 1 color laser print, 1965

- NASA Apollo 11: 2 chromogenic prints, 1969, 3 gelatin silver prints, 1969, 1 video, 1969

- Neil Armstrong: 3 chromogenic prints, 1969, 1 dye transfer print, 1969/later, 1 gelatin silver print, 1969

- Dmitri Baltermans: 1 gelatin silver print, 1951

- NASA Ranger 9: 1 gelatin silver print, 1965

- Edwin Buzz Aldrin: 1 chromogenic print, 1969

- CBS News: television coverage of Apollo 11 moon landing 1969

- 1 Hasselblad 70 mm camera, and film magazine, 1969

- 2 lunar globes, c1963, 1969

Art After Apollo

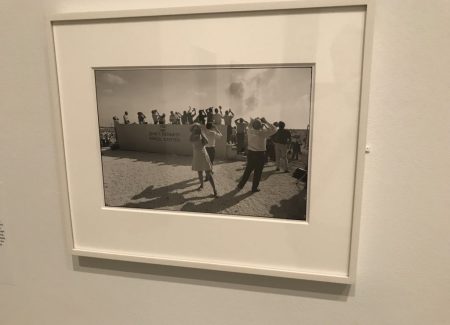

- Garry Winogrand: 1 gelatin silver print, 1969

- Robert Rauschenerg: 1 lithograph and screenprint, 1969, 1 solvent transfer with watercolor, gouache, pencil, and colored pencil, 1969

- Charles Drake: 1 color laser print, 1972

- John Chamberlain et al.: lithograph of tantalum nitride on ceramic wafer, 1969

- Paul van Hoeydonck: 1 aluminum replica, 1971

- David Scott: 1 inkjet print, 1971/2019

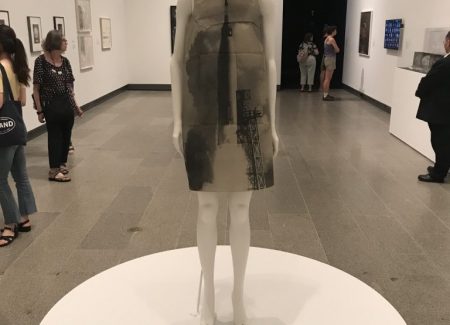

- Harry Gordon: 1 screenprinted tissue, wood pulp, and rayon mesh dress, 1968

- Nam June Paik: 1 digital video transferred from 16mm film, 1966-72

- Alessandro Poli: 4 photomontages, 1970-71

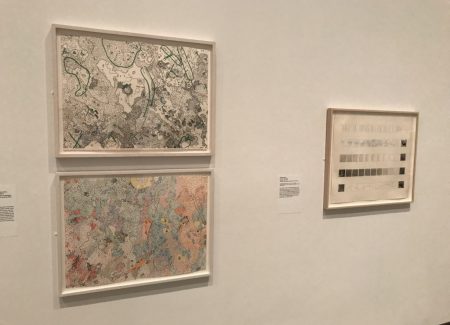

- Nancy Graves: 2 lithographs, 1972

- Michelle Stuart: 1 graphite, colored pencil, and gelatin silver prints, 1969

- Judy Dater: 1 gelatin silver print, 1981

- Aleksandra Mir: 1 digital video of live event, 1999

- Stephen Shames: 1 gelatin silver print, 1971/later

- Cristina de Middel: 1 inkjet print, 2012

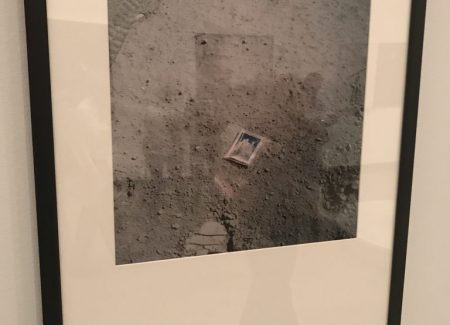

- Vik Muniz: 1 gelatin silver print, 1990

- Jojakim Cortis and Adrian Sonderegger: 1 chromogenic print, 2014

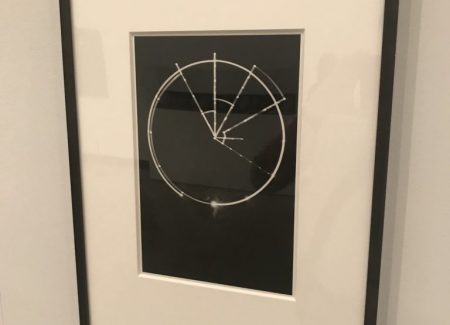

- Lenka Clayton: 1 ink, 2015

- Penelope Umbrico: 1 single-channel video, color, 2015

- Sarah Charlesworth: 2 chromogenic prints with lacquered wood frames, 2012

- Darren Almond: 1 chromogenic print, 2000

- Kiki Smith: 1 accordion-fold book, 1998

- Sharon Harper: 1 chromogenic print, 2004

- Kikuji Kawada: 1 gelatin silver print, 1969

(Installation and detail shots below.)

A catalog has been published by the museum in conjunction with the exhibition (here). Hardcover, 192 pages, with 150 color illustrations. With essays by Mia Fineman and Beth Saunders. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: The Apollo 11 moon landing on July 20, 1969 was a human milestone unlike any other. With the whole world watching on live television, Neil Armstrong stepped down onto the dusty surface and brought to fruition years of intense effort, hard work, scientific breakthroughs, and aspirational dreams. As a species, in that one singular historic moment, we radically expanded our human boundaries, successfully leaving our own planet behind to visit and explore the shining faraway object inhabiting our nighttime skies. To walk on the moon (and live to tell about it) was literally the culmination of thousands of years of wonder and inspiration.

On the 50th anniversary of that astonishing achievement, this exhibit considers the role photography has played in our evolving love affair with the moon, and that story is longer, richer, and more varied than we might remember. From the first invention of the medium, we have pointed our cameras at the moon, and the results have oscillated widely between the rigorously scientific and the boldly imaginative. The moon has long been a mystery to us, and photography has provided a powerful method for trying to answer our endless list of questions.

At its core, this exhibit is built around a loose before-and-after narrative arc—it starts with our looking-up photographs of the moon before we actually went there, pauses to look carefully at the images made in the run up to and surrounding the landing, and then surveys a few of the moon-centric pictures and artworks we have made since that time. In many ways, this is an ageless tale about the acquisition of knowledge—of the unknown becoming known, and how our collective mindset has changed as a result.

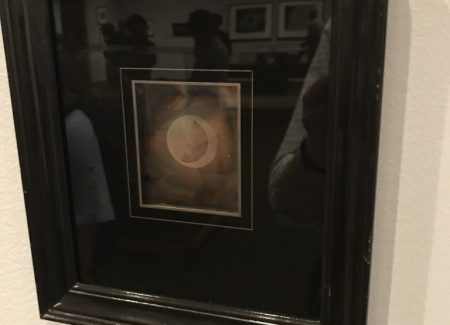

The first part of the story is really scientific history, beginning with Galileo in 1610 and the invention of the telescope. The first telescope led to the first hand drawn images of the lunar surface, which were reproduced as etchings, and as the technology behind the telescope incrementally improved, so did the accuracy of the early moon maps. When photography arrived on the scene in the early 1840s, it was immediately applied to the lunar mapping challenge, but the complex interconnected combination of the long exposure times, the rotation of both the Earth and Moon, and the blurring distortion of the atmosphere made the task of delivering crisp photographs extremely difficult. Daguerreotypes by John William Draper and John Whipple showed the promise of applying photography to lunar mapping, and by the 1850s, Warren De La Rue had pushed the effort forward with wet-collodion glass negatives and clockwork mechanisms that started to compensate for the mid-exposure shifting. By the end of the century, dry plate negatives shortened exposure times considerably, and, in combination with improvements in both telescopes and clockworks, ultimately led to the authoritative lunar map made by Maurice Loewy and Pierre Puiseux in Paris in 1894. All 83 mammoth plate photogravures from their ground-breaking atlas are on view in a side gallery, and the precise detail of the enlargements is undeniably impressive; an alternate set of 48 views (published by their assistant Charles Le Morvan in 1914) arranges the images into more lyrical waxing and waning sets, which grace the external walls of the exhibit. Seen as a progression, this first section of the show sets up a string of technical obstacles which were one by one overcome by persistence, innovation, and ingenuity.

The second part of the show circles back to this same early period and traces not technological advancements but the artistic whimsy of our many lunar fantasies. This section is less strictly chronological or additive, instead gathering together an eclectic selection of interpretations of the moon, not all of them photographic. With its soft crescent moon and its craggy surrounding trees, Caspar David Friedrich’s 1825 painting Two Men Contemplating the Moon captures the romance, mystery, and even awe that were routinely applied to the floating orb in the night sky in the 19th century. Edward Steichen’s The Pond – Moonrise from 1904 uses photography to generate a similarly moody impression, with the sliver of rising moon peeking through a veil of dark trees. Somber reflection is then transformed into dreamlike enchantment in Georges Méliès landmark 1902 film A Trip to the Moon (seen here in both preparatory drawings and video clips), with a cannon-shot space vehicle that hits the moon right in the eye and a surface exploration trip that visits an underground grotto filled with giant mushrooms. A light-hearted group of vernacular “Man in the Moon” postcards from the early 20th century find people of all kinds posing for studio portraits with (and on) smiling cardboard crescent moons. And even Man Ray got into the act, adding a photogram light stitch to an image of the moon in his 1931 Électricité portfolio, playfully implying we might turn the light of the moon on and off.

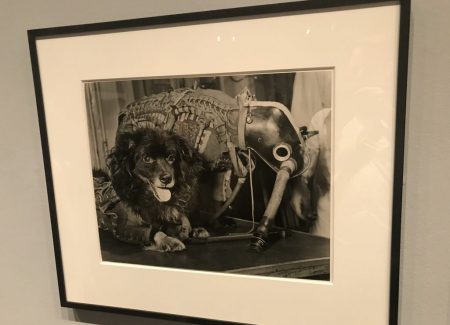

With these parallel scientific and artistic viewpoints of the moon now set up, the exhibit moves on to the actual 1969 moon landing and the imagery that was made during the various orbital missions that took place in the months and years prior. Beginning with the Soviet space dogs of 1957 and the USSR Luna 3 view of the previously unseen dark side of the moon from 1959, we bounce through a selection of increasingly detailed reconnaissance views of the moon’s surface (taken by probes, orbiters, and other machinery), many created via the compositing of physical prints or the scanned assembly of video frames, strips, and blocks of isolated imagery into larger wholes and wall-filling mosaics – these scientific and technical images of the moon were orders of magnitude more detailed than anything ever seen before; in our attempt to understand what is important about each one, this section of the exhibit would have benefited from a more step-by-step explanation of the progressive operational improvements that were taking place with each successive mission.

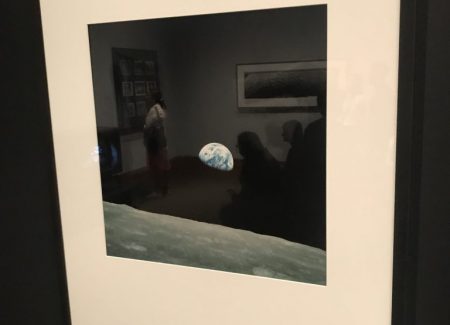

This section also includes some of the now-iconic photographs from these missions, the ones that forever changed our collective sense of self. Two of the most memorable images aren’t of the moon at all, but of the Earth as seen from space. William Anders’ Earthrise (from the Apollo 8 mission in 1968) and Harrison Schmitt’s Blue Marble (from the Apollo 17 mission in 1972) both tug on our sense of home, and remind us of the fragility and vulnerability of our planet against the vast backdrop of the universe – these pictures recalibrated our sense of place in the cosmos, our planet suddenly seeming quite a bit more lonely and insignificant. Neil Armstrong’s images of Buzz Aldrin walking around in his space suit, posing with an American flag, and working on the lunar module tell a different story – one that is human scaled and personal, but also operatically grand. The exhibit also recreates the intimate feeling of watching Armstrong descend the stairs from the comfort of our living rooms back on Earth (via an antique TV replaying the live feed). Visitors to the show seemed mesmerized by the recreated moment, many taking pictures of the setup from their smartphones – even 50 years later, the drama of the event can clearly still hold the attention of even the most distracted museum goer.

Unfortunately, the last section of the show (hung across the hallway) doesn’t draw out the artistic influences, learnings, or consequences of the moon landing with much clarity. It brings together a broad group of artworks made since the Apollo 11 mission, but doesn’t really tie them into any particular thesis or argument – the moon is their subject, but their motives or lessons are diffuse. Kikuji Kawada and Sharon Harper use the moon itself to provide the light for multiple exposure drawings and dappled fields of tiny spots, Judy Dater and Alexandra Mir sharply reimagine moon landings with women as the protagonists, Vik Muniz and Jojakim Cortis/Adrian Songderegger unpack and conceptually recreate a pair of the famous images, and Penelope Umbrico smartly mines the Internet for thousands of images of the moon. All of these (and other solid inclusions from Cristina de Middel, Sarah Charlesworth, and others) fit the larger framework, but fail to deliver any obvious overarching conclusions about the cultural impact of the moon landing, in either the immediate aftermath or much later.

As an integrated experience, Apollo’s Muse certainly does a commendable job of bringing the 1969 moon landing (and photography’s critical role in that endeavor) back into the public eye. Perhaps the show would have benefited from removing the last contemporary section (or dividing it off into its own separate show, as has been done with some of the Stonewall memorials) and adding in more moon-centric art from the 1950s and 1960s (during the run-up to the landing), which is altogether absent from the narrative. There is much to be savored in this scientific/artistic hybrid show, but the artistic side of the house isn’t as well fleshed out and articulated as it might have been. Luckily, the central inspiration of this moment in history is so powerful, we hardly mind.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibit, there are of course no posted prices, and given the large number of artists included, we will dispense with our usual discussion of individual gallery representation arrangements and secondary market histories.