JTF (just the facts): Published in 2014 by Onomatopee (here). Hardcover, 272 pages, with 254 color and black and white reproductions. Includes texts by Brad Feuerhelm and the artist, as well as a transcript of email exchanges between the two. The book is printed on a variety of matte and gloss paper stocks, which are matched to the different image sets. A special edition of the book (including 5 inkjet prints and other materials) is available here. (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: For the past several years, we’ve been gingerly dancing around the idea that straight appropriation – the kind originated by the Pictures Generation artists in the 1970s and that kicked off the careers of artists like Richard Prince – has finally run its course. Finding a photograph, taking it out of its original context, and presenting it unedited in a new (or redacted) context just isn’t enough anymore; the earlier appropriations still have their power, but modern versions of these same ideas are meaningfully less challenging and uneasy. And while the networked reality of the digital Internet has made vast troves of imagery now available for artistic reuse, it’s become clear that the simple intervention of discovery and re-presentation doesn’t go far enough; bombarded by image overload, we’ve become numb to such obvious and facile thinking.

For many, the next idea in the evolutionary path of archival appropriation has been to start with a selection of found material/ephemera (vintage, vernacular, whatever) and to use those pictures as the baseline for the reconstruction of a loose after-the-fact quasi-narrative, especially when the backstory to the images is unknown. This digs into a photograph’s ability to simultaneously conceal and reveal, and to be reinterpreted at a later date by a new set of eyes. Some artists are then interleaving their own contemporary photographs in with the found ones, as a method for taking control of the sequenced narrative and pushing it in a desired direction. This has led to a wave of photobook projects with mysterious, open-ended stories, where shards of faded vintage images leave us grasping for the full details and newer pictures collapse time. And yet I’m not convinced that many of these complex editing efforts will be durably important; they feel like a stepping stone to somewhere else, rather than a discrete and defensible destination of their own.

To her credit, Anouk Kruithof has deftly avoided these first two potholes with her recent investigation of a vernacular archive – there are few straight stand alone appropriations and no overtly imposed story arcs to be found in The Bungalow. Starting with 500 digitized images from Brad Feuerhelm’s larger collection, she locked herself away in a cabin and binge ingested the entire mass of eclectic imagery, soaking and steeping herself in it, allowing the natural taxonomies and categorizations that are implicitly overlaid on such a collection to dissolve away. There is a mood of sitting-in-the-dark obsessiveness in this self-imposed isolation process, like a solo photographic drug trip in search of out-of-bounds transformations or the bug-eyed Jack Nicholson pounding away on his novel in The Shining and coming out with something truly unexpected.

Kruithof’s photobook is really four books in one, as it gathers together four (or arguably five) different interpretive bodies of work that emerged from her journey down the vernacular rabbit hole. Each is distinct response to the imagery she had as her raw material, each a separate investigation of not just the subject matter itself, but of the wholesale conceptual restructuring she was imposing on the pictures. In a sense, she uses Feuerhelm’s collection as the central launching point for multiple artistic explorations that venture off in opposite directions.

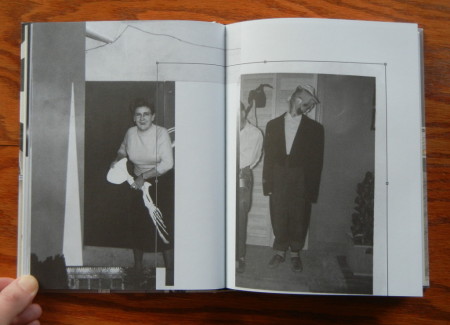

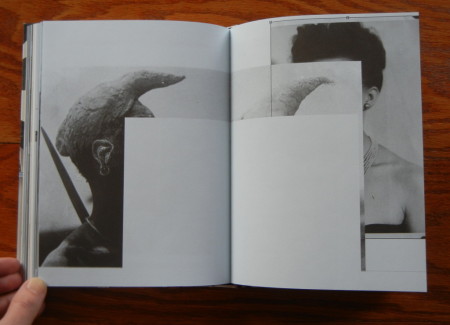

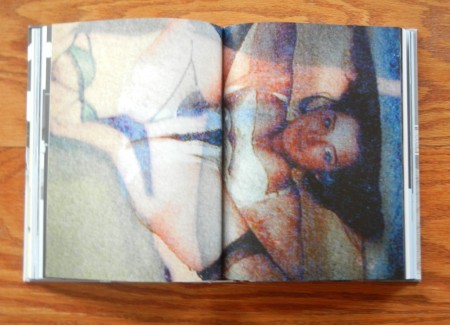

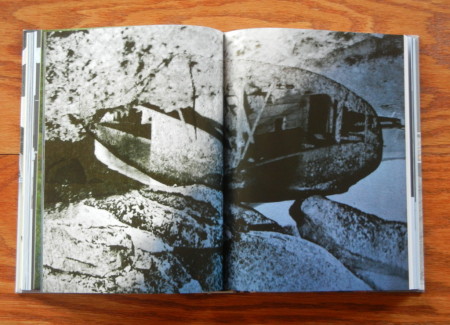

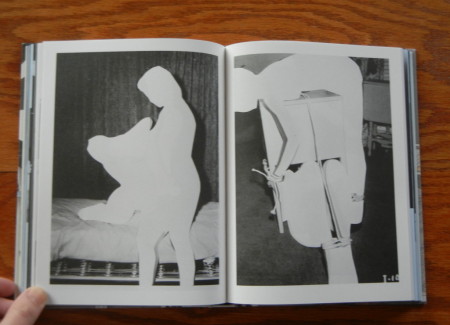

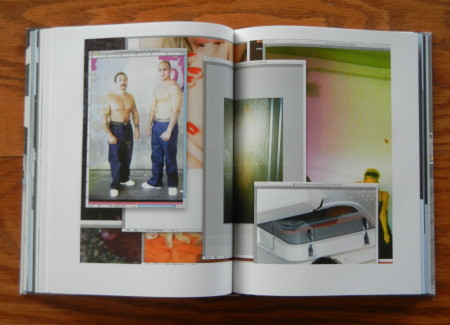

Two sets of the resulting images are essentially analog ideas, where the physicality of the photographs is being thoughtfully manipulated. In one, pairs of color images of women are collapsed together like Robert Heinecken’s magazine works, creating grainy double exposure composites that pile bodies and faces into “split personalities” (this same process is used on a few images of rocks and bunkers, but to lesser impact). These works feel like a distant relative of her own bisected face self-portraits from 2011 (a project called The Daily Exhaustion), albeit with a more uncertain set of emotional resonances. In a second project, Kruithof brings out the scissors and physically cuts away the women in bondage photographs, turning them into ghostly white silhouettes or jittering collages of other imagery. While this kind of erasure has been done before (Jose Dávila comes to mind), its pairing with the specific subject matter here gives the process more punch – she’s reconsidered the blatant voyeurism and objectification inherent to the pictures (and the actions) and instead offered up an empty cutout negation.

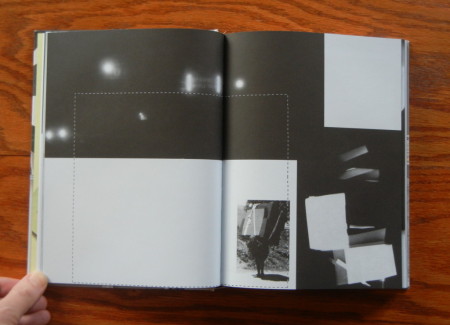

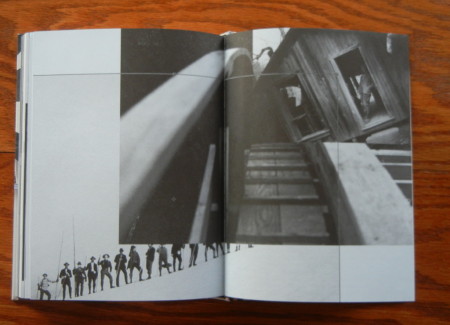

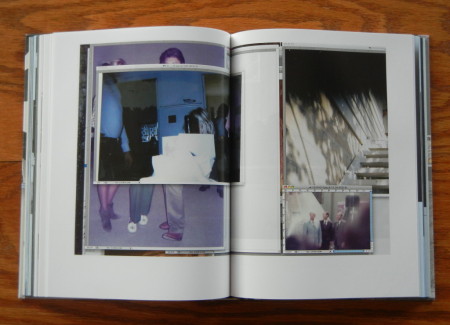

The other two bodies of work included in the book are more fully realized and much more digital in their mindset. Both throw away the primacy of the physical print and fully embrace a screen-based interface, where images float on an indeterminate rectangle and are swiftly rearranged with a click of the mouse. In one group (printed on light blue paper), vernacular selections in black and white are gathered into small impromptu still lifes, seemingly captured mid-creation, with the gridlines, resizing frames, and other software artifacts of Photoshop still part of the compositions. Some repurpose two or three images into exercises in visual form, while others lean towards Baldessari-like rebuses and combinations of obliquely related items. When Kruithof applies these techniques to obviously vintage material, the aesthetic effect is pleasingly puzzling, as modern geometric cursors and dashed boxes hover over fragments of lost time. I like the sense of immediacy and curiosity in these digital constructions; there is the sense of looking over the artist’s shoulder and watching her actively and improvisationally reshape her visual reality.

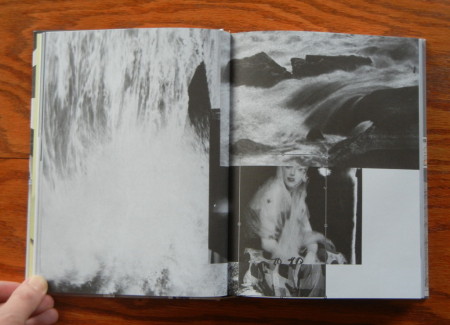

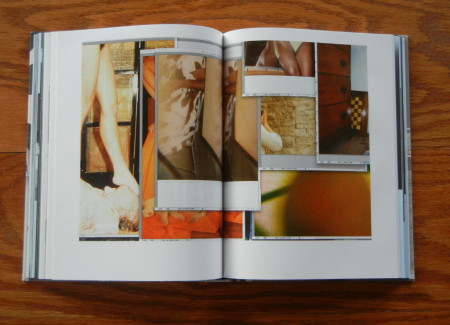

The last group of works moves back into bright glossy color, and uses the user interface windows of the software more obviously as picture frames. These screenshots are less like still lifes and more like never-ending stream of consciousness layers, where tiles of imagery overlap and get pushed down, each new addition rebalancing all of the ones underneath it like a social media timeline. Here we are brought back to grasping at elusive narrative, trying to connect the dots between adjacent images that seem to hint at some larger hidden meaning. But again, Kruithof leaves us with a feeling of digital impermanence, as if her combinations are fleeting and ephemeral, captured in the one moment before they burst apart into untraceable bits once again. What’s intriguing and original here is that the outer rectangle of the image edge does not correspond to the various windows inside – she’s documented a disjointed, enveloping desktop of overflowing, fragmented pictures, echoing the assault of imagery we experience daily and the processes (conscious or unconscious) that we all employ to give those images meaning and context.

Conceptually, in the span of this single book, Kruithof has made a major break with the everyday photographic appropriators that we are accustomed to – she has both walked familiar paths and then daringly jumped with both feet into a new digital mode of seeing, quickly recalibrating her eye for this new environment. Risk taking like this has the potential to open up big white spaces for artistic exploration, and this screenshot interface point of view feels like the beginning of something new and innovative. It breathes fresh life into tired appropriation, giving it the ability to be cacophonous, and active, and multi-layered, and messy, in ways that it has never been before.

Collector’s POV: Anouk Kruithof is represented by Gallery Boetzelaer Nispen in Amsterdam (here). Her work has not yet reached the secondary markets with any regularity, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.