JTF (just the facts): A total of 21 color photographs exhibited in four rooms on white walls. All are pigment prints, back-mounted on dibond, framed in wood, and dated 2015. Eighteen of the prints are sized 60×50 inches, the other three are 40×30 inches. Seventeen are in editions of 3+2AP; four are in editions of 7+2AP. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Andres Serrano’s first solo exhibition in New York since 2008 is a calamity. As an admirer of his work in the past, I take no pleasure in reporting that my strongest reaction was disbelief that a body of work could be so ill-conceived. As I walked around the gallery rooms, I found my mind less engaged by the images, which are big and ominous but lifeless and prosaic, than by the several ways in which his pre-production decisions may have doomed his efforts.

The theme of the show is torture, a thorny subject under any circumstance, especially in the context of high-priced collectible art. By no means should historic catastrophes, natural disasters, and personal traumas be out of bounds to art photographers. But anyone hoping to breathe new life into momentous issues, such as slavery, the Holocaust, nuclear hazards, sexual criminality, Sept. 11, the aftermath of hurricanes, tornadoes or wildfires, should be aware that photojournalists were probably there first and may have already exhausted much of the oxygen supply. Unless an art photographer can find an oblique angle of attack that editorialists, scholars, novelists, and film-makers have not previously exploited, any pictures about these issues, however well-intentioned, will be blunted by the sheer enormity of the heavily dented and fortified target.

Serrano isn’t sure where to find vulnerabilities in his subject that would allow his audience—all too familiar with images of people maimed or imprisoned—to empathize strongly or expand their thinking about the body and pain. When he isn’t being crudely literal—he has a photograph of 19th- century slave shackles—he relies on the cheesy pathos of reenactment. For a series of four photographs, he asked a group of Irish men, known as the “Bag Men,” to recreate the stress positions they were forced to endure when imprisoned by the British. Curled up and naked in empty jail cells but otherwise bearing no marks of physical harm, they could be demonstrating modern dance or yoga poses. Only the gallery’s press release, with the explanation by Serrano, reveals what the men are trying to portray. The photographs on their own do almost nothing to provide us with a visceral understanding of torture’s lasting physical and mental price, or the motivation of the torturer.

Several other portraits recreate the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison. These infamous acts of humiliation and terror, documented in cell-phone photographs by the jailers, who then jokingly shared them with their friends, sparked an international outcry when published in 2004. Artists and writers around the world responded quickly to the visual proof of Americans as torturers. Richard Serra did several oil-stick drawings of the “Scarecrow Man” in 2004. Even the usually upbeat Columbian artist Fernando Botero was moved to create 87 drawings and paintings of the prisoners in 2005.

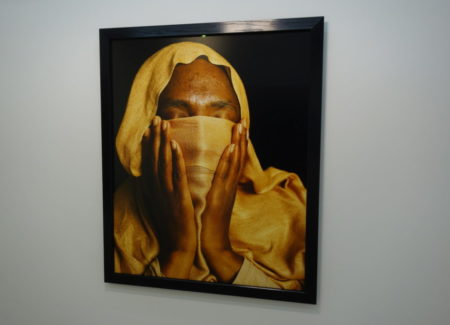

Why Serrano should feel the need to revive these widely circulated images now is a mystery. Compared to the beheadings by ISIS—or even the slaughter of innocents at My Lai—the ritual degradations of prisoners at Abu Ghraib seem relatively tame. His photographs don’t contribute to the debate about who is more to blame for the actions of the guards—the oblivious managers of the prison or the blithely overconfident and unprepared Bush administration. He has posed his actors without any complicating apparatus, in empty dark warehouses, many with their heads hooded, the standard procedure of rendition for prisoners by the CIA post-2001. Photography and the internet played a crucial role in both encouraging and disclosing the torture at Abu Ghraib, paradoxical issues that are nowhere addressed in this work.

As in the past, Serrano is interested in suffering as a state of grace, and once again, relies on Christian iconography to underline his points. The hooded figures in their rough brown burlap robes recall Zurburán’s 17th century paintings of Spanish monks and saints. One of the trim and muscled actors here is blindfolded and bound to a wooden horizontal post protruding from a concrete wall—a form of persecution so primitive it could have originated before ancient Rome. In another large image two large wooden planks are crossed, with strands of rope wrapped around the upper half of the X. St. Andrew was crucified on this sort of device, a crux decussate or saltire. A wooden chair, presumably for the interrogator, stands in the foreground. But to suggest that contemporary victims of torture and Christian martyrs are connected by a shared spiritual destiny would require more intellectual tissue than Serrano’s superficial photographs can provide.

The only truly unsettling image is one of red rubber gloves, wet and sticky, on the sill in a small concrete window. Whether these are worn by the torturer or the person who cleans up after, they are the accessories of a fastidious monster who doesn’t want to dirty his/her hands when busy with wet work.

Blood is a handy cliche for invoking horror. A thick pool of it covers the floor of what appears to be a prison cell in one image here. The splashing has left a stain on a bare mattress. Whether this photograph depicts an actual crime location or is another reenactment we aren’t informed, as if that weren’t an important distinction. I suspect the scene was entirely constructed by Serrano, probably with non-human blood.

Without discounting the misery and hardships of the people Serrano has chosen to portray, and whose trust he was careful not to violate, it’s not impertinent to wonder if he could have more effectively dramatized the scars left by state-directed pain on their bodies and minds. I don’t know if the history of violence can be more searchingly delineated in large-scale conceptual programs, like the ones that Taryn Simon has tried to manage. I can only speak to the confused and disappointing results of this present strategy.

Collector’s POV: The prints in this show range in price from $26000 to $57000. Serrano’s work is consistently available in the secondary markets, with recent prices ranging from roughly $5000 to $185000.

Your disappointment is palpable, and I’m almost scared off commenting, but not quite! At least you were a fan, which is something. I’ve rarely met anyone who seems to have a good word to say about him, including photographers whose work I admire. He’s dismissed for all sorts of reasons but, once again with this curious (dis)integration of fact/fiction, there’s something valid here. The links provided were helpful in understanding the background.

Rather than “suffering as a state of grace” I think Serrano usually reaches to affirm divinity in spite of the profane. It’s a very personal search. Torture is merely another manifestation where the weakness of the flesh is made brutally evident and opened for consideration.

You mention Taryn Simon at the end, definitely a different approach but not one I’d place above Serrano in terms of philosophic or intellectual relevance.