JTF (just the facts): A total of 19 color photographs (8 inkjet prints and 11 c-prints) hung in 3 galleries of the museum’s main exhibition space and along both sides of the central corridor. The works date from 1984 to 2014 and print dimensions vary from 24 ¼ by 30 to 81 ½ by 140 ¼. A companion catalog, with an essay by Terrie Sultan, has been jointly published by Gagosian Gallery and the Parrish Art Museum (hardcover, 68 pages, 24 color and black-and-white illustrations, $45.) (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: This selection of images seems targeted more at novices unfamiliar with the work of the great Gursky than at those who have tracked his vaunted career through museums and auction houses.

Not that I’m complaining. In the airy rooms of the long, single-story, barn-like building, designed by Herzog & de Meuron, the 19 photographs here, some of them from the pre-digital 1980s and therefore far less grandiose than his more renowned mural-sized productions, display a leisurely confidence in Long Island’s late summer light.

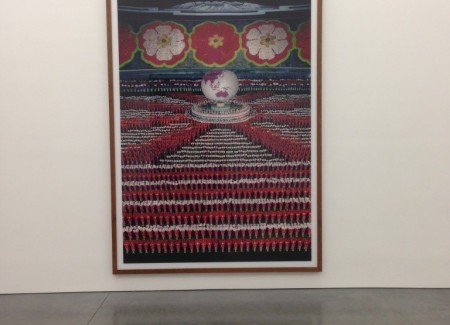

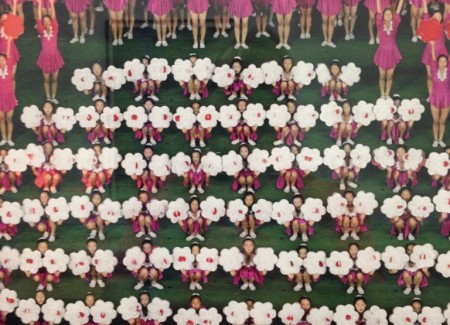

The Parrish director, Terrie Sultan, has chosen a couple of the pictures that appeared in the 2001 MoMA retrospective, including the by-now classic Rhein II, but the majority here were not. The places depicted are roughly divided between land and sea, urban and rural. There are intricately detailed scenes full of highly crowded human and animal activity, and there are sparsely organized, desert-like scenes where nothing moves.

Sultan’s catalog essay locates the German-born photographer within the Western landscape tradition and finds affinities between his obsessions and those of painters Casper David Friedrich, Albert Bierstadt, and Frederic Church.

The analogy is apt, so far as it goes, in that none of these 19th-century artists pretended to be objective naturalists but rather sought to impress audiences with their own personal sense of the sublime. The popularity of Church and Bierstadt depended partly on the exoticism of their dispatches from remote areas of the Americas, just as Gursky has gone to Antarctica and Asia and the Middle East in search of knock-your-eyes-out images.

Early works, such as Schiphol (1994), reveal his first successes at merging the histories of photography and painting. His camera views the airport’s runways through the windows of a glass-and-steel pavilion. It could be a document of modernist industrial architecture by Albert Renger-Patsch or Julius Shulman. Except that the cloudy skies and the flat horizon line also indicate that Gursky has been looking hard at Hobbema and Ruisdael landscapes and wants us to know he has been thinking about time and art history.

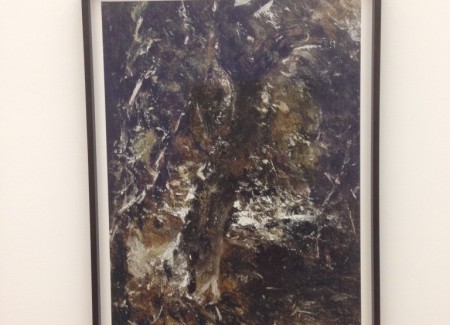

Like Jeff Wall’s tableaus, Gursky’s landscape photographs are in a competitive dialog with painting. If the horizontal bands in Rhein II are his digital take on a Mark Rothko, then the dark vertical lines in Bangkok IX (2011)—another large-scale (121 by 87 inches) minimalist abstraction, of reflections in water—is his Barnett Newman or Clyfford Still.

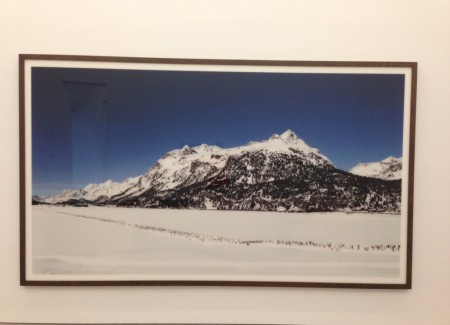

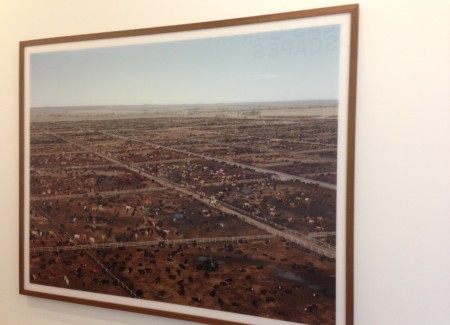

Whatever redemptive vision of Nature’s healing spirit Gursky hopes to convey, however, is tempered by a candor about the impact of human intervention and greed on the land. The biting or deadpan wit in many of his photographs has little in common with the guileless panoramas of the Hudson River school. When Gursky depicts the earth as a site for contemplation or pleasure, it’s often over-crowded; the foreground of Engadin I includes hordes or cross-country skiiers snaking across the manicured Alpine snow. Landscapes are either so twisted and scarred they resemble a black-tarred Escher puzzle (Bahrain, I) or they’re a bleak resource where workers and the soil are both exploited. The feed lots of the cattle ranch in Greeley resemble a concentration camp, and the asparagus pickers in Beelitz seem no better off than the insect pests they pull off the plants.

As he has matured, and his hand has become heavier on the digital keyboard, Gursky’s photographs have less in common with his nonjudgmental fellow Becher-trained contemporaries, Thomas Struth and Candida Höfer, and more with Sebastião Salgado and Edward Burtynsky. (Such comparisons to these two preachier artists, both such too fond of the God’s-Eye-View, are not intended to be compliments.) Decorative impulses are also swelling the scale of his prints and obscuring the original, grittier documentary substrate. In a show that inadvertently contrasts his inkjet and c-prints, the older technology seems clearly to be the better medium for his images.

Gursky once said, “I am never interested in the individual, only in the human species and its environment.” This no longer is the case, as recent examples here indicate. Two of the landscapes at the Parrish are populated by solitary Marvel superheroes. His diptych of a brooding Superman (2014) portrays the Man of Steel posed like Rodin’s thinker, surrounded by barren rings of stones, in near total darkness except for a full moon. Ironman (2013) stands on a palm-framed beach in the violet dusk, poised to embrace Pepper Potts (the character played by Gwyneth Paltrow in the movie franchise), their faces illuminated by the uni-beam projection gun from his chest armor.

While smiling at Gursky’s sense of the absurd—the Superman image has the mock solemnity of Christ in the garden at Gethsemane; Ironman and his love interest gaze at one another like honeymooners in a Maui travel poster—I also can’t help noting the calculation behind the idea of matching comic book icons and a million-dollar living artist. Hollywood producers and actors are not the only customers for this sort of high-priced, boy-oriented kitsch, but they are certainly a target audience.

As karmic payment for such cynicism, Gursky is now enjoined (as is this website) from freely reproducing these images. Thanks to North Korea, which hacked Sony’s emails, we can read about the groveling involved, even for an artist of Gursky’s stature and with Gagosian’s muscle behind him, to negotiate with a corporate entity that controls a lucrative copyright-able property, such as a superhero (here).

The most mysterious photograph in the show is of a single human being. Katar (2012) is a dazzling image of an interior. Light bounces off a metal surface that could be either gold or copper, the reflections enveloping walls, ceiling and floor. It is tempting to interpret the space as the vault of an American bank or depositary, perhaps Ft. Knox. Instead, we are told that it’s the inside of a container ship and the shrouded figure in the lower left corner, cocooned inside a white muslin tent, is an attendant. How the photographer came upon this scene, why he chose to depict it, and what he intends it to mean, as either document or metaphor of economic reality, is not clear.

As Peter Galassi wrote in his MoMA essay, “Gursky’s polished, signature style is the fruit of restless experiment; the more he has welcomed divergent and often mutually antagonistic impulses into his art, the more it has become his own.”

When awesomeness and irony are held in balance, and they often are, Gursky is a superb artist. Engadin I (1995) was taken in Sils Maria, the village in southern Switzerland where Nietzsche wrote Thus Spoke Zarathustra and other prophetic books in the 1880s, and where Gursky regularly vacations with his family. The massive size of the snow-covered Alp behind the thin, sketchy line of tiny skiiers reads like one of the philosopher’s cosmic, misanthropic jokes about human folly. Long after this crowd of athletic enthusiasts has died of heart attacks, the mountain will remain.

Not so funny is that a commercial gallery has been allowed to co-sponsor an exhibition by one of the prize thoroughbreds in its stable at a public art museum. Without condemning the Parrish for its cozy relationship with the Gagosian Gallery, which I am guessing was dictated by the financial necessity of insuring these expensive works, I do find it questionable, if not shameful, that the enterprise was permitted to put its name under the title on the wall. Or perhaps it’s fitting that the art of the dealer is showcased during the summer of Trump.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices. Andreas Gursky is represented by Gagosian Gallery (a sponsor of this exhibit) in New York (here). Gursky’s prints are routinely available in the secondary markets, with his Rhein II among the most expensive photographs ever sold at auction, topping $4.3 million. While some Gursky prints in large editions can be found for under $10000, most start at roughly $50000 and work their way up to over $1 million, with a handful bumping up into the $2 million and $3 million range.