JTF (just the facts): A paired show of photographs and enlarged details from paintings, on view the the main gallery space and the smaller back room. (Installation shots below.)

Andreas Gursky works included in the show:

- 3 inkjet print, Diasec, 2021, 2023, 2024, sized roughly 85×160, 74×160, 82×101 inches, in editions of 6+2AP

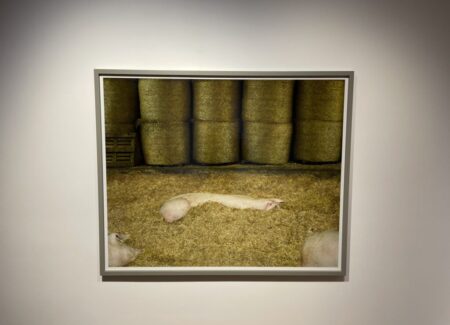

- 1 c-print, 2020, sized roughly 48×59 inches, in an edition of 6+2AP

- 1 fine art print, 2023, sized roughly 43×36 inches, in an edition of 12+2AP

Referenced works (as wall installations):

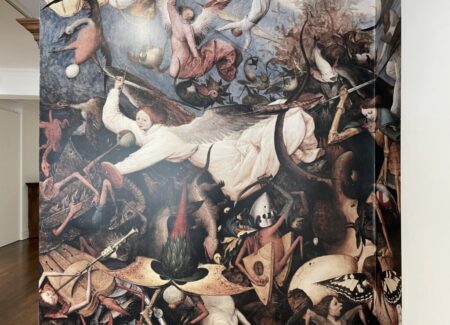

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Fall of the Rebel Angels, 1562, oil on oak panel (detail)

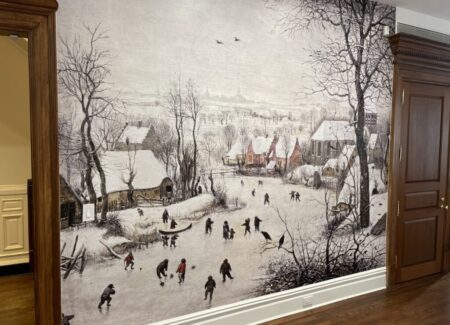

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Winter Landscape With Skaters and a Bird Trap, 1565, oil on oak panel (detail)

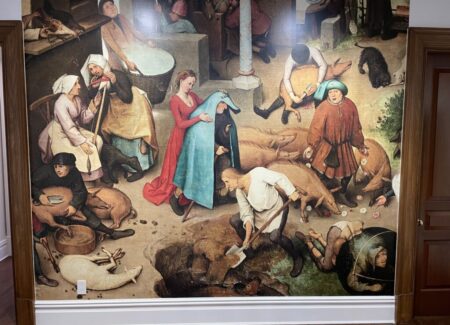

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Dutch Proverbs, 1559, oil on oak panel (detail)

- Carl Gustav Carus, The Sea of Ice Near Chamonix, 1825-1827, oil on canvas (detail)

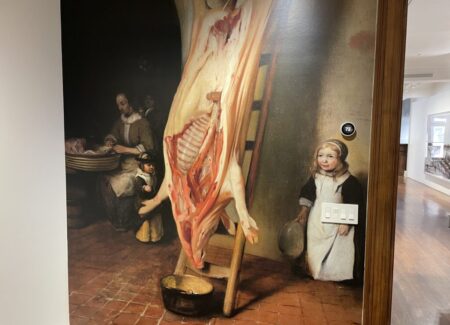

- Barent Fabritius, The Slaughtered Pig, 1656, oil on canvas (detail)

- JWM Turner, Fishermen at Sea, 1796, oil on canvas (detail)

Comments/Context: Back in the mid to late 1990s, Andreas Gursky boldly used photography to provide a muscular counterpoint to painting. At that time, his combination of monumental scale and precise digital manipulation was ground breaking, and his subsequent art market success seemed to signal that acceptance of the digital transition that was taking place in photography was indeed gaining momentum.

In the decades since, Gursky has continued to make big pictures, and to push photography into deeper dialogues with painting. And while his photographs have never been particularly “painterly” in the sense of being aesthetically gestural or improvisational – he has always stayed close to the crisp realistic details provided by a camera (and digital software) – Gursky’s images have consistently raised themselves up to match the drama, majesty, heft, and scope of the massive history paintings and controlled tableaux of centuries past, albeit with contemporary subject matter and context.

This small show only includes five photographs – three works made in the past couple of years and two previously seen in Gursky’s 2022 gallery show at Gagosian Gallery (reviewed here) – but the edit has been tightly crafted to amplify the active conversation Gursky is having with the history of painting. Each photograph has been paired (by Gursky) with a specific painting from the past, with relevant fragments of the original works enlarged and printed on wall-filling installations that flank the nearby photographs. The setup encourages a direct back-and-forth visual comparison, each pairing highlighting both what inspired Gursky in these artworks and how his photographs consider some of the same themes and compositional approaches.

The newest Gursky image in the show is a 2024 view of the Aletsch Glacier in Switzerland. The largest glacier in the Alps, it’s likely been the subject of many grand mountainscapes and natural views over the years, but Carl Gustav Carus’s “The Sea of Ice Near Chamonix” from the mid 1820s isn’t one of them; it actually documents the similarly impressive Mer de Glace in France on a sunny day. But the visual echo of the two compositions is obvious, with ice sweeping down through a valley between the mountains like a frozen river. What separates the two pictures is their divergent moods – for Carus, the glacier was a location of pristine natural beauty to be celebrated, but for Gursky, the effects of global climate change have made his view much more dispiriting and critical; dirty tracks now slither through the muddy ice, with more and more dirt exposed on the surrounding mountains amid the misty clouds. In many ways, in all its glorious, expansive detail, Gursky’s photograph is remarkably incisive and ominous, the future of this once astonishing natural wonder now very much in question.

The climate crisis is also at the center of Gursky’s 2023 image “Lützerath”. The work documents climate activists who have taken up residence in the trees around the village in North Rhine-Westphalia, after plans to expand an open-pit coal mine nearby were announced. The activists are variously perched in the trees, waiting in tents on makeshift platforms, hanging signs, lounging in hammocks along strung wires, and otherwise aboveground, while scattered riot police stand below looking up at the circus-like activity. It’s a photograph without an obvious center, with many smaller visual anecdotes and incidents taking place at once in two tiers, certainly reminiscent of the all-over complexity of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s 16th century compositions. Nearby, Gursky has chosen Bruegel’s 1562 “The Fall of the Rebel Angels” as a companion, with a swirlingly similar pitting of good against evil, with white-robed angels flying through the air above a range of armed grotesqueries below.

Bruegel also provides inspiration for Gurksy’s 2021 image “Eisläufer”, which documents the frozen floods of the nearby Rhine, with its impromptu ponds and skate paths of ice in the riverside parks. It’s a dense wall-filling winter scene, with hundreds of figures ice skating, sledding, playing hockey, pushing strollers, tending children, walking dogs, and generally enjoying the fleeting winter fun. Bruegel’s “Winter Landscape with Skaters and a Bird Trap” (from 1565) offers a more modest version of this kind of public spectacle, with fewer skaters and children but a similar sense of communal participation and enjoyment.

The other two Gursky photographs included in the show are less expansive. One looks upward into the night sky above the Maldives, finding an inky wash of blurred clouds shrouding the glowing moon; it recalls the dark romanticism of a late 1790s nocturnal seascape by JMW Turner (which is installed above and around the gallery fireplace). The other features a pig buried up to its back in hay, making its pink skin (and pointed ears) appear to mysteriously float in the textured soup of straw; its nearby companion is altogether more ruthless, taking shape as a hanging pig carcass in a slaughterhouse, as seen in a 17th century painting by Barent Fabritius, with yet another painting by Bruegel (on the opposite wall) offering echoes of textured pig skin.

For those less familiar with Gursky’s efforts to place photography on an equal footing with painting, these pairings will likely help to connect some of the dots of his aesthetic argument, albeit in a quite literal one-to-one matching way – by revealing some of his influences, he’s creating undeniable equivalencies. But for those who have been following Gursky’s career more closely, the recent works find him engaging with the politics of climate change with more force and energy than ever before, redirecting his aesthetic energy in support of advocacy and action. In this way, the few new works on view here remind us that when Gursky successfully directs his considerable photographic powers toward a hot-button cultural issue, he can still be as relevant as he ever was.

Collector’s POV: The large works in this show are priced between €100000 and €850000, based on size. Gursky’s prints are routinely available in the secondary markets. While some Gursky prints in large editions can be found for under $10000, most prints start at roughly $50000 and work their way up to over $1 million, with a small handful bumping up into the $2 million and $3 million ranges.