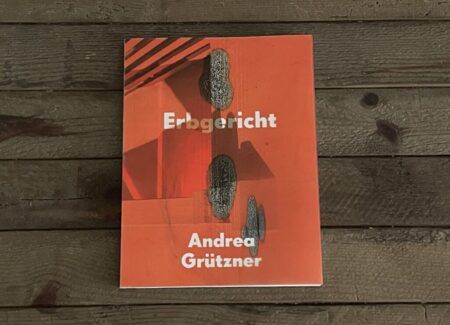

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Hartmann Books (here). Softcover with open thread stitching, 22.7 × 29.8 cm, 128 pages, with 114 color and black-and-white reproductions. Includes a printed PVC film cover, and an enclosed text booklet with essays by Eric Meier and Cora Waschke (in German/English), an interview between Jeannette Brabenetz and the artist (in German/English), and a thumbnail list. Design by Johanna Flöter. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Can a photographic genre have an “opposite”? In both concept and execution, I think the answer can surprisingly be yes, as seen in photographic landscapes that intentionally make it hard for us to see the land or photographic portraits that frustrate our ability to engage with the sitters. Andrea Grützner’s photobook Erbgericht offers another thought-provoking example of this kind of deliberate inversion, in architectural photographs that visually disorient the built space they ostensibly document.

Grützner has spent much of the past decade photographing the inside of a single structure, the erbgericht in her hometown of Polenz, in Saxony, Germany. Originally built in 1898, the three-story building has had many uses over the years, most often as a country inn or guesthouse, with common facilities shared by the residents of the regional community. Inside, it’s a modest hodgepodge of dated materials, renovations, and furnishings with unassuming stylistic echoes of the 1960s, 1980s, and 1990s mixed together in the details. Grützner first visited the erbgericht when she was a young child, so the place carries with it histories, associations, and memories from not only her own life, but of the generations past.

If Grützner had set out to make “architectural photographs” of this building, we can reasonably predict what they might have looked like: exterior views of the building in its surrounding environment, systematic interior views of the various rooms, and perhaps even close up views of particular architectural details, with an eye for giving us a feel for the spaces and for the stylistic decisions made by the architect (or architects over time). But essentially none of Grützner’s photographs in Erbgericht function in this way. Instead, she has used the building as pliable raw material for her own sophisticated investigations of space, structure, texture, and color, disregarding whatever conventions might plausibly apply to the genre.

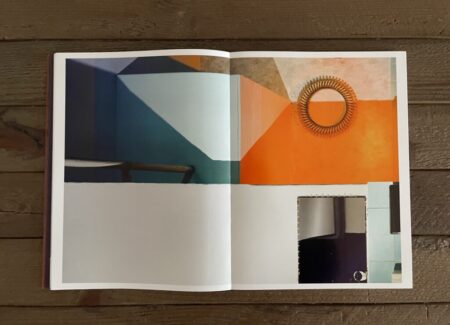

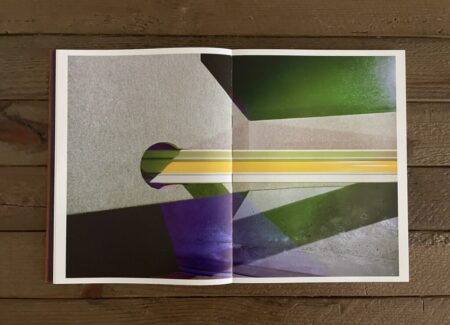

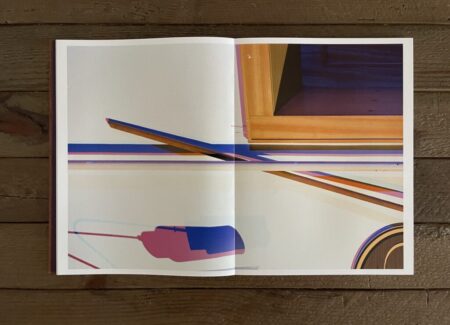

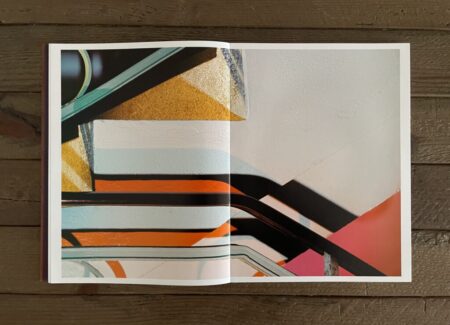

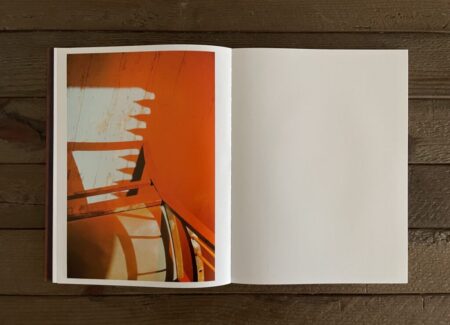

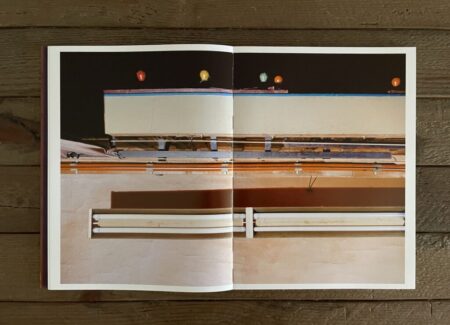

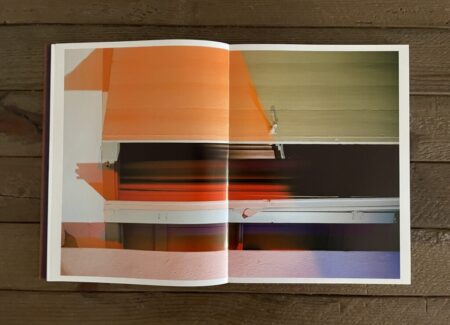

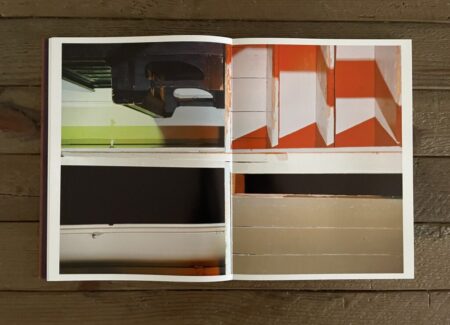

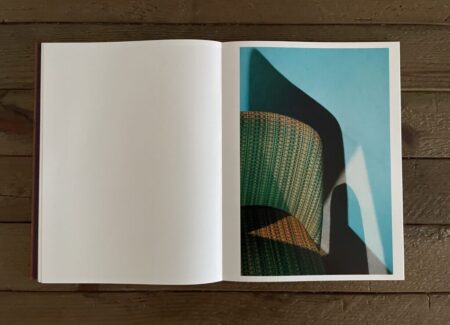

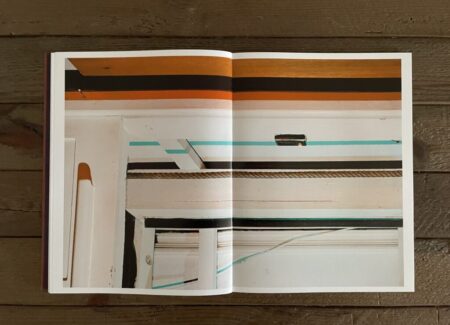

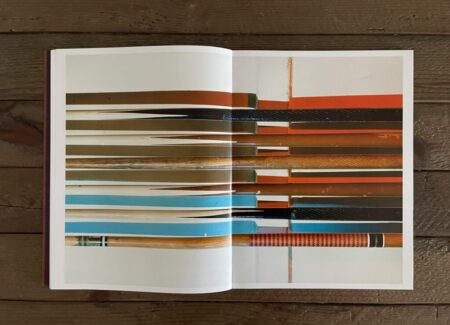

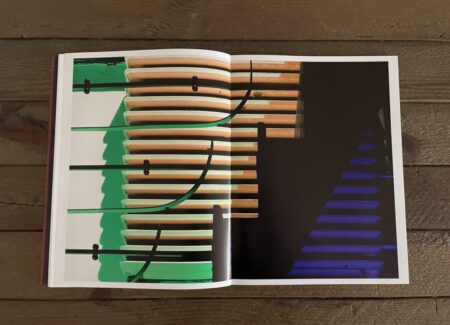

Working with a large format camera and meticulously lighting the available spaces with multiple flashes covered in colored gels (thereby creating layers of geometries, tints, and shadows), Grützner’s setups playfully experiment with the ways a camera flattens the depth of actual space into a single plane. In terms of their subject matter, her pictures could hardly be more forgettable: walls, floors, ceilings, stairs, doorways, windows, carpeting, tile, railings, wood paneling, and stucco, with the resulting empty spaces then populated by light fixtures, pieces of furniture, mirrors, curtains, pipes, hooks, vents, and even a piano and a rack of pool cues. But in Grützner’s hands, these overlooked everyday details become altogether disorienting, turning the familiar into the unfamiliar.

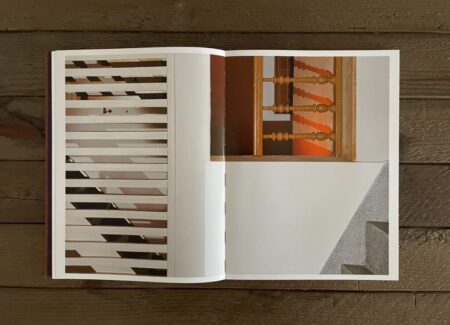

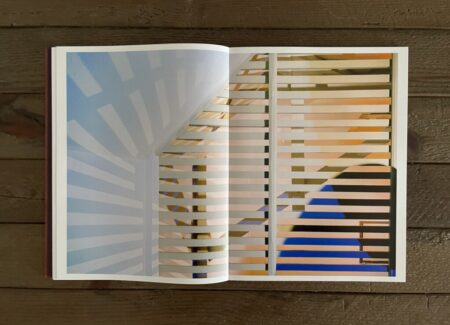

To my eye, the strongest of Grützner’s compositions are the ones that make the most of confounding our ability to decipher them. Repetitions of wooden slats and their shadows dance across surfaces, becoming confused with similar patterns in radiators, chair backs, stair steps, and aligned doors; soon the racked pool cues (and their shadows) get in on the action, as do clusters of fluorescent light bulbs, vertical pipes, and curtain rods, some seen from underneath looking up. The more she pushes toward unidentifiable geometric abstraction, the more the whole exercise feels like a methodical visual deconstruction, or a breaking down of the usual dynamics of surface and space.

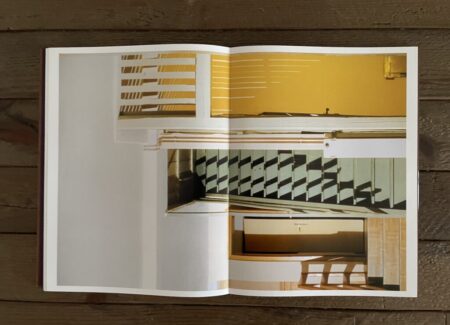

Grützner’s photographs are generally vertically oriented (meaning they are taller than they are wide, as seen in her 2016 gallery show of early images from the project, reviewed here). But even when we intellectually understand this orientation information, it doesn’t mean that we can reliably tell up from down or left from right in her pictures. Often overall size and scale have been shifted or enlarged (especially when the prints are big), and compositions have sometimes been rotated or hung upside down, confusing our typical sense of where the ceiling and floor might be. This spatial ambiguity is further amplified by the way Erbgericht has been constructed as a photobook, in that most of the images have been rotated and printed across both sides of a spread, turning vertical into horizontal again and again.

One of the fascinating puzzles to be found in Grützner’s complex compositions is that not only do we have to figure out the classic question of where the camera has been placed, but we also need to consider where various lighting sources are coming from, as multiple colored shadows activate nearly every image. In this way, her precisely fragmented views of rooms become covered with colored geometric shapes and elongated or angled echoes, sometimes including the intruding shadow of something outside the frame. Each photograph becomes its own visual situation or compositional experiment, sometimes seen in multiple iterations with different lighting options (as in “Untitled 05”, “Untitled 09”, and “Untitled 10”, which feature the same setup in variations of orange, blue, and yellow.)

While light and shadow play important roles in Grützner’s photographs, any quick flip of Erbgericht will likely be most remembered for its disorienting pops of color; for an interior largely covered in drab tones of painted white, cream, and light woods, this is a photobook bursting with exuberant blasts of primary color. Apparently the reproductions were made with an extended 7-color offset printing process which makes the colors all the more vibrant. Seen in sequence, Grützner’s compositions really do start to feel like studies of how she can “inhabit the space with my colors”. This idea is then extended further to image scans of her sheets of colored gels (some with scrapes and melt marks), and a transparent PVC film dust jacket printed in purple, orange, and green, which creates its own layers of tinted interaction with the images underneath.

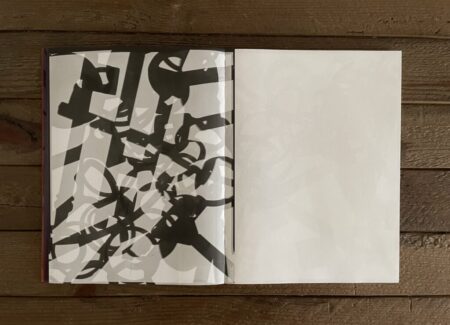

Erbgericht begins and ends with photograms of keys, where layers of keys (presumably to the building) shift and intermingle until they drift into abstraction. Perhaps they signify a process of entry and exit, of coming, going, and locking up each time, or maybe they are simply another way of turning the obvious physicality of the place into something visually malleable. Either way, they too are activated by light, and made into something mysterious.

Collector’s POV: Andrea Grützner is represented by Robert Morat Gallery in Berlin (here) and Schierke Seinecke Gallery in Frankfurt/Main (here). Her work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.