JTF (just the facts): A total of 24 black-and-white photographs, framed in black and matted, and hung against white walls in the three room gallery space. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made in 1942 and printed recently; additional details about the photographs (dimensions, edition sizes, etc.) are not provided, but lengthy image titles/captions written by the artist are shown on wall labels. The show also includes 1 magazine spread, 1 photograph/document, and 1 color video (2022, 12 minutes, 18 seconds). (Installation shots below.)

A museum exhibition of this same body of work (featuring nearly 60 prints) was recently on view at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts (here, January 6-June 23, 2024).

A monograph of this body of work was published in 2024 by Steidl (here). Hardcover, 25 x 29 cm, 192 pages, with 136 image reproductions. Includes essays by Philip Brookman, Melanee C. Harvey, Hank Willis Thomas, Salamishah Tillet, and Deborah Willis. (Cover shot below.)

Comments/Context: Singular standout photographs often take on a sprawling cultural life of their own, so much so that over time, we can often lose track of the particular context of how, when, and even why the picture was made in the first place. This small exhibit (and the accompanying monograph) takes as its centerpiece “American Gothic”, the now-iconic photographic portrait Gordon Parks made of Ella Watson standing in front of a flag in 1942. The show offers a deeper dive into the backstory of this famous image and the larger project of which it was a part, filling out the history with two dozen images that broaden our understanding of not only “American Gothic” itself, but of how Parks was thinking about (and documenting) the realities of segregated Black life in America during that time.

In the summer of 1942, Gordon Parks was 29 and living in Washington, D.C., on a year long fellowship working at the Historical Section of the FSA (Farm Security Administration) under Roy Stryker. As Parks was finding his footing and looking for subjects that might fit his interest in documenting the realities of Black life in America, Stryker introduced him to Ella Watson, a custodian (or “charwoman”) working in the building where the FSA offices were located. As it turned out, Watson had been a federal employee for twenty-six years and was caring for a family of six, including a number of grandchildren, on her meagre government salary of $1080 a year. Over the period of roughly a month, Parks collaboratively photographed Watson and the rhythms of her life, following her daily routines and ultimately making more than 90 images.

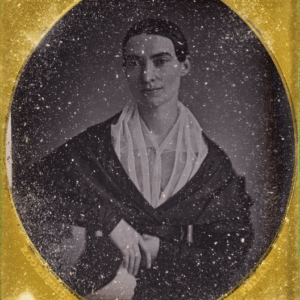

When Parks brought back the photograph that would later be called “American Gothic” (it originally had a more straightforward descriptive caption), Stryker knew immediately that Parks had crafted something special. Parks had posed Watson with her upturned broom and mop in front of an American flag hanging in an empty office, recalling Grant Wood’s composition of a white farmer (with his upturned pitchfork) and his wife. Parks allowed the flag to drift into blur, while focusing his attention on Watson’s calm but unwavering expression. The effect was quietly powerful, creating a contrast between the dignified hard-working efforts of everyday Black Americans and the patriotism (that didn’t seem to include Watson) implied by the flag. The directness of the image put the issues of race, injustice, and poverty front and center, to the point that the photograph was thought to be too provocative and was never actually used by the government.

This show, of course, begins with “American Gothic” (on the first front facing wall) but quickly moves on to other images that Parks made of Watson, her family, and her community. The central wall in the main gallery space is filled with images of Watson at work, including a variant composition of “American Gothic” stepped back a few paces to include more of the surrounding office environment, with the mop and broom nearby instead of held up. Parks patiently watches as she methodically mops bathrooms, sweeps dark hallways and areas near desks, empties trash cans, and poses with a bucket and brush. These images are activated both by Watson’s quiet fortitude and by Parks’s compositional inventiveness with shadows, mirror reflections, stacked trash cans, and other available motifs.

Another small group of photographs sensitively documents Watson’s home life, where she lives in modest quarters with various young grandchildren and her adopted daughter and her child. Parks finds her holding children, reading to them from the Bible, and sitting more contemplatively in front of an improvised altar of religious objects and candles on the top of a dresser, the included mirror used by Parks to add reflected figures to the scenes. Even though Watson’s poverty is implied, Parks never portrays her as a victim, but instead honors the hard work and dedication seen in the support of her extended family.

The bulk of the imagery on view in this show actually builds on this religious theme more fully, with Parks following Watson to her local church and visiting other Black churches nearby. In a sense, the Watson that Parks finds at church is somewhat different than the one he saw at work; dressed in all white, she is a church deaconess, an intellectual and social leader in her congregation, with the status that such a role represents (in contrast to the underpaid government cleaning woman working alone at night). Parks’s photographs document religious rituals at various churches, including Watson’s own, mixing the expressive singing and clapping many Black churches are known for with a more restrained and measured piety, as seen in particular in the focused attentiveness of Watson’s demeanor as she receives blessings. But an underlying consistency of character is clearly present, in the self-effacing and nurturing care that Watson provided for her family similarly applied to her broader church community.

While “American Gothic” has already proven that it can clearly stand on its own as a single photograph, what this show reminds us is that Parks was actually trying to document a richer and more complex reality than any one image can represent. By placing emphasis on Watson’s participation in her religious community, Parks makes a portrait of Black life that isn’t just a retelling of physical labor and poverty; it instead gives Watson agency, and honors her pursuit of religious knowledge and spiritual reflection as ways to create hope in the segregated world of 1940s Washington, D.C. His celebrated portrait of Ella Watson isn’t just a (staged) decisive moment, but a more nuanced and three-dimensional view of a Black woman building a dignified and worthy life inside the constraints and stratifications of her times.

Collector’s POV: The gallery representation relationships for Gordon Parks are somewhat tricky to unravel. Some galleries clearly represent the Parks estate, while others are putting on shows of his work that may or may not represent a fuller relationship. Some of the galleries where Parks’s work can be found include Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York (here), Jack Shainman Gallery in New York (here), Rhona Hoffman Gallery in Chicago (here), Weinstein Hammons Gallery in Minneapolis (here), and Alison Jacques Gallery in London (here). Parks’s prints have been only intermittently available in the secondary markets in recent years, with recent prices ranging between $2000 and $24000.