JTF (just the facts): An expansive group show of diverse artworks, installed across all the floors of the newly opened museum and its many ancillary spaces. All of the works are drawn from the museum’s permanent collection. The exhibit was organized by Donna De Salvo, Carter E. Foster, Dana Miller, Scott Rothkopf, Jane Panetta, Catherine Taft, and Mia Curran. (Installation shots below.)

The photographers included in the show are listed below, along with background details on the number of works on view, their processes and dates. The works have generally been organized into thematic groups with titles, as follows. Sections without any listings do not include any photography:

01. Eight West Eighth

- Berenice Abbott: 1 gelatin silver print, 1938

- Cecil Beaton: 1 gelatin silver print, c1931

- Charles Sheeler, 3 gelatin silver prints, 1923, 1928

- Edward Steichen: 1 gelatin silver print, 1931

- William Winter: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1932

02. Forms Abstracted (none)

03. Music, Pink and Blue

- Imogen Cunningham: 1 gelatin silver print, 1931

- Alfred Stieglitz: 1 gelatin silver print, 1923

04. Machine Ornament

- Ilse Bing: 1 gelatin silver print, 1936

- Margaret Bourke-White: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1930

- Lewis Hine: 1 gelatin silver print, 1930-1931

- Man Ray: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1922, 1923

- Toyo Miyatake: 1 gelatin silver print, 1932

- Edward Steichen: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1929, 1930

- Ralph Steiner: 1 gelatin silver print, n.d.

05. Breaking the Prairie

- Ansel Adams: 1 gelatin silver print, 1941

06. Rose Castle

- Walker Evans: 1 gelatin silver print, 1931

- Andreas Feininger: 1 gelatin silver print, 1949

- Man Ray: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1931, c1940

07. Free Radicals (none)

08. The Circus

- Roy DeCarava: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1960, 1961

- Robert Frank: 1 gelatin silver print, 1954

- William Klein: 1 gelatin silver print, 1955

- Lisette Model: 2 gelatin silver prints: 1940-1944/1950s, 1945

- Edward Steichen: 1 gelatin silver print, 1933

- Weegee: 2 gelatin silver prints, c1940, 1943

09. Fighting With All Our Might

- Margaret Bourke-White: 1 gelatin silver print, 1937/1970

- Walker Evans: 1 gelatin silver print, 1936

- Dorothea Lange: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1934, 1935

10. New York, N.Y., 1955 (none)

11. 7th Floor Outdoor Terraces (none)

12. White Target (none)

13. Scotch Tape

- Stan VanDerBeek: 1 gelatin silver print, 1965

14. Large Trademark

- Robert Adams: 1 gelatin silver print, 1969/1970

- Diane Arbus: 1 gelatin silver print, 1968/1969-1971

- John Baldessari: 1 photographic emulsion on canvas, 1966-1968

- Lewis Baltz: 1 gelatin silver print, 1972

- William Eggleston: 2 dye transfer prints, 1972/1980, 1965-1974/2002

- Lee Friedlander: 1 gelatin silver print, 1965-1973

- Bill Owens: 1 gelatin silver print, 1970

- Garry Winogrand: 1 gelatin silver print, 1968/1981

15. Raw War

- Larry Clark: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1971/1972

- Danny Lyon: 1 gelatin silver print, 1963

- Gordon Parks: 1 gelatin silver print, 1970

16. Rational Irrationalism (none)

17. 6th Floor Outdoor Terraces (none)

18. West Ambulatory off of 1970s Painting (none)

19. Threat and Sanctuary (none)

20. Learn Where the Meat Comes From

- Asco: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1977, 1978, 1 chromogenic print, 1974/2011

- Alvin Baltrop: 1 gelatin silver print,1977

- Hans Haacke: 9 photostats, 142 gelatin silver prints, 142 photocopies, 1971

- Paul McCarthy: 9 gelatin silver prints, 1975

- Ana Mendieta: 1 gelatin silver print, 1973, 1 chromogenic print, 1979

- Adrian Piper: 14 gelatin silver prints, 1971/1997

- Liliana Porter: 1 photoetching and graphite pencil, 1974

- Lucas Samaras: 2 dye diffusion transfer prints (Polaroids) with hand applied ink, 1971

- Cindy Sherman: 4 gelatin silver prints, 1978, 1979, 1980

- Laurie Simmons: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1976, 1 chromogenic print, 1979

- Sturtevant: 1 gelatin silver print, 1966

- Hannah Wilke: 1 gelatin silver print, 1974

- Francesca Woodman: 1 gelatin silver print, 1976

21. Racing Thoughts

- Sarah Charlesworth: 2 silver dye bleach prints, 1987/2012

- Barbara Kruger: 1 photoscreenprint on vinyl, 1987

- Louise Lawler: 1 cibachrome print, 1988

- William Leavitt: 3 chromogenic prints, 1977/2011

- Richard Prince: 1 chromogenic print, 1983

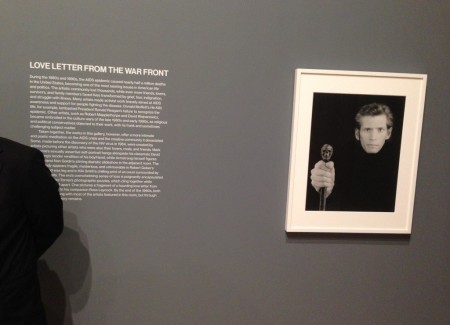

22. Love Letter From the War Front

- David Armstrong: 1 gelatin silver print, 1980

- Sue Coe: 1 photoetching, 1990

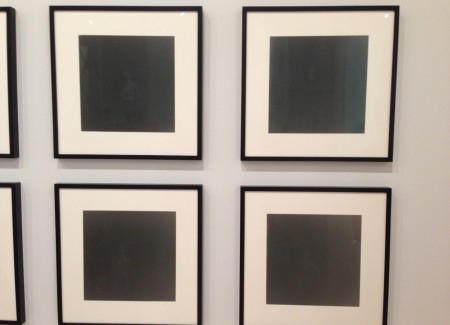

- Nan Goldin: 1 slide installation (690 35mm color slides), 1979-1996

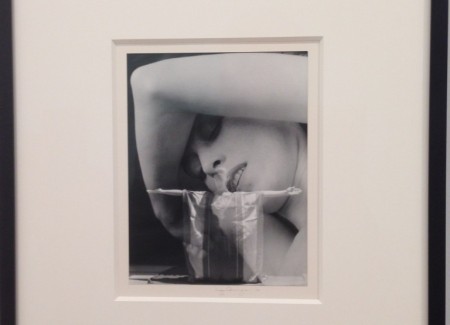

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres: 2 chromogenic print jigsaw puzzles in plastic bags, 1989

- Peter Hujar: 2 gelatin silver prints, 1976, 1985

- Robert Mapplethorpe: 2 gelatin silver prints,1977, 1988

- Mark Morrisroe: 1 chromogenic print, 1985, 1 silver bye bleach print, 1981/1984

- David Wojnarowicz: 3 gelatin silver prints, 1989

23. Guarded View

- Catherine Opie: 1 chromogenic print, 1993

- Lorna Simpson: 3 gelatin silver prints and 2 plastic plaques, 1990

24. Distracting Distance

- Christopher Williams: 1 chromogenic print, 2006

25. Course of Empire

- LaToya Ruby Frazier: 2 gelatin silver prints, 2011

- Zoe Leonard: 6 dye transfer prints, 1999/2000, 2001

- An-My Lê: 1 gelatin silver print, 2003-2004

- Adam McEwen: 1 chromogenic print, 2004

- Abelardo Morell: 1 gelatin silver print, 2002

- Taryn Simon: 1 chromogenic print, 2007

26. East Ambulatory adjacent Course of Empire (none)

27. Arcade Gallery (none)

28. Get Rid of Yourself Program A/B (none)

29. Mezzanine, Hallway to Kauffman Gallery

- Michele Abeles: 1 inkjet print, 2012, 1 pigment print, 2014

- Anne Collier: 1 chromogenic print, 2007

- Roni Horn: 2 chromogenic prints, 2001

30. Elevators (none)

31. Lobby (none)

32. Theater Gallery

- Anne Collier: 1 chromogenic print, 2009

- Bruce Nauman: 11 chromogenic prints, 1966-1967/1970

33. Theater Screening Program (none)

34. 8th Floor Entrance Hallway (none)

Comments/Context: American Visions: The Epic History of Art in America by Robert Hughes was one of 1997’s cultural blockbusters. The BBC-produced TV series, written and hosted by the Australian-born historian and critic, ran for nearly 8 hours on PBS, while the 635-page companion volume, published by Knopf, became a bestseller.

Hughes’s chronicle assessed 350 years of paintings, sculptures, buildings, urban parks, monuments, and items of furniture. Delivered with his usual manly swagger, the narrative was unapologetically personal, loaded with strong opinions and astute insights, and told from a foreigner’s POV. The more distant, Toquevillean perspective was supposed to remove any hint of jingoist triumphalism from the epic tale. Hughes was a fine critic, as entertaining on the screen as on the page. He could spot the “weird” meanings of Bingham’s Fur Traders Descending the Missouri and bring the same analytic gusto to a discussion of the “psychic daring” in De Kooning’s Woman I. He blasted the temporizing politics that excused the displacement and slaughter of the Indian and the promotion of the slave trade in the 19th century. His sensitive nose for BS in contemporary art mocked Julian Schnabel’s self-grandiosity in the 1980s and the culture of political correctness in the 1990s, identity politics being a movement, Hughes thought, that was strangling free artistic expression.

The series was generally well-received with a few notable exceptions. Several academics thought he had appropriated their scholarship without giving them credit—a fair accusation—and in an otherwise laudatory review, Louis Menand observed in the New York Review of Books that a few major elements were conspicuously missing from the epic tale.

After praising Hughes for his erudition and high spirits, the review asked why this history of American art had failed to highlight its visionary achievements in photography, cinema, and television: “If someone were to list the distinctly American contributions to world culture, and the arts from which Americans have taken their understanding of themselves,” Menand wrote, “these are the <three> arts they would name.”

He further commented that many of the painters and sculptors in American Visions were European-trained (Bierstadt, Moran), had worked mainly outside the U.S. (Copley, Sergeant, and Whistler in England), or were epigones of movements born elsewhere (Impressionism and Cubism.)

American photographers and filmmakers, Menand might have added but didn’t, were not as beholden to European models; indeed, for some years the influence flowed the other way. Hughes grants Stieglitz a decent amount of space, albeit as a promoter of Modernism, but Robert Frank merits only two passing citations: once as a friend of De Kooning, the other as a friend of Franz Kline. (American Visions, believe it or not, has not a word to say about The Americans.)

Brazen and brilliant as Hughes could be in charting the highs and lows of his adopted country’s history, any story of American art that omits Edward Steichen, D.W. Griffith, Edward Weston, John Ford, Ansel Adams, Maya Deren, Berenice Abbott, Howard Hawkes, Helen Levitt, or Orson Welles is telling only a pale, decaffeinated version of American art history. And those are only the credits that should roll for the first reel of the 20th century.

***

America is Hard to See, the exhibition inaugurating the Whitney Museum of Art’s new $422 million home in the meatpacking district of Manhattan, isn’t nearly as barren of photography, movies, and television examples as Hughes’ history. Film and video are found in the installation on at least three of the six floors; and photographs are spread throughout, in rooms with paintings and sculpture as well as with other print media. The building also now has a theatre for screenings and performances.

Organized chronologically into 23 thematic “chapters,” each one named for “a work that evokes the section’s animating impulse,” America is Hard to See displays art across all mediums, and side-by-side, “acknowledging the ways in which artists have engaged various modes of production and broken the boundaries between them.”

Work has been installed, according to the opening text, in “a conscious effort to unsettle assumptions about the American art canon” and to underscore “the difficulty of neatly defining the country’s ethos and inhabitants”, a challenge that lies at the heart of the museum’s commitment to and continually evolving understanding of American art.

Curators have presented art across disciplines many times before. Modern Starts, the series of exhibitions that MoMA initiated in 2009, blended even more genres (with architecture and design added to the mix.). The Met’s current survey, Reimagining Modernism, has followed suit. One might say this “impure” approach, instead of being a radical departure from curatorial form, has become the standard in exhibiting contemporary art.

The decision to tell the story of American art in this manner has benefits for other media at the Whitney. Sculpture is given room to stretch its arms and legs in the museum’s airy, light-filled galleries. I doubt that Mark di Suvero’s Hankchampion (1960) or David Hammons Untitled (1992) have ever looked better in any room or context than they do here. De Kooning’s Door to the River (1960), placed near a window, beckons you to step through the layers of overlapping color into another, less material dimension. The maelstrom of forms and pinks in Lee Krasner’s The Seasons (1957) is allowed to outmuscle Pollock’s Number 27, 1950 (1950) across the room. Other works of art strike up conversations with neighbors they might not otherwise meet. The woman with the blue headband in Alex Katz’s The Red Smile (1963) might very well have a bad enough nicotine habit to have filled the ashtray in Claes Oldenburg’s Giant Fagends (1967).

As the Whitney has only been buying photographs since 1990, my photographic expectations for the show were not high that it could overcome the shortcomings of what is a young and patchy collection of images. The sample on the walls is generous under these circumstances: of the 650 or so titled objects, about 75 are photographs.

What’s disappointing is that the Whitney’s curators, led by Donna De Salvo, are really no better than Hughes at presenting the dynamism of 20th century American photography. The playfulness so visible with Katz, Hammons, and De Kooning does not seem to have governed the placement of works by, say, Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, William Eggleston, or even Man Ray. Only in a couple of rooms did I come upon photographs keeping unfamiliar company or located within a larger complex of adjoining works that released new and unexpected meanings. For the most part, the reverse was true: the themes chosen by the curators to tell the story have shriveled ambiguity, flattening rough edges so that they fit more snugly into a social or political narrative. In about one-third of the 23 chapters, none or only one photograph can be found.

The list of artists who should be here and are missing would begin with Alvin Langdon Coburn, Paul Strand, Edward Weston, Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind, Frederick Sommer, Minor White, O. Winston Link, Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Duane Michals, Ray Metzker, and Stephen Shore.

Numerous artists who have explored their own performances with a camera are here, including Adrian Piper, Bruce Nauman, Asco, Paul McCarthy, Cindy Sherman, and Lucas Samaras. But there are no examples of Big Color from the 1990s or the “New Materialists” of the past decade. Helen Levitt’s photographs aren’t here, only her brilliant collaborative film In the Street. Kenneth Josephson (subject of a pioneering Whitney retrospective by Sylvia Wolf in 1999) is nowhere to be seen, while William Eggleston (subject of another ambitious Whitney retrospective, by Elizabeth Sussman in 2009) has only two prints here, both so badly hung they are easy to miss.

Even some of the photographers lucky enough to make the cut—I’m thinking particularly of Stieglitz, Roy DeCarava, Robert Adams—look diminished in the areas they are assigned. Robert Frank has one print in the show, and it’s not from The Americans. If the stated aim of the curators was to “unsettle assumptions about the American art canon,” they succeeded.

To judge purely by numbers (admittedly a crude metric), Nan Goldin is by a wide margin the greatest American photographer of the last century. Her slide-show Ballad of Sexual Dependency has 690 images and a room of its own. So does Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, a Real-Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971. It has the next largest number of photographs (142 gelatin silver prints), followed by Piper’s Food for the Spirit from 1971 (14 gelatin silver prints), Nauman’s series of goofy autobiographic performances from 1966-67 (11 c prints), followed by McCarthy’s Experimental Dancer from 1975 (9 gelatin silver prints).

After these artist-photographers, the fall-off in numbers is precipitous: 6 by Zoe Leonard, 5 by Steichen, 4 by Sherman, 4 by Man Ray, 3 by Lange, 3, by Charles Sheeler, 3 by Margaret Bourke-White, 3 by Laurie Simmons, 3 by David Wojnarowicz, 2 by Evans, 2 by Samaras, 2 by Weegee, 2 by DeCarava, 2 by Lisette Model, 2 by Peter Hujar, 2 by Robert Mapplethorpe, 2 by Larry Clark, 2 by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, 2 by Mark Morrisroe, 2 by Anne Collier, 2 by Michele Abeles, and singletons by everyone else, including Stieglitz.

There is no mention of “photographic vision” as an influence on painters, nor of print quality and social engagement (as a divisive issue, one to be embraced or avoided) for artists through the decades. Questions of which artist might be more dominant than another at a particular time (Picasso or Pollock or Frank or Arbus or Kossuth or Sherman) are ignored in favor of wall texts about art’s political roles. And neither the chapters describing these changes nor the photographers chosen to represent them are altogether surprising.

The Great Depression (“Fighting with All Our Might”) has single works by Lange, Bourke-White, and Evans, while the AIDS epidemic (“Love Letter from the War Front”) has a poignant ensemble by Wojnarowicz, Hujar, Morrisroe, and Mapplethorpe. Only in the chapter on the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights movement (“Raw War”) do unaccustomed partners make for original dialogue. The politics of opting-out is clearer in a pair of Larry Clark photos from 1971 (one is of a guy shooting up heroin, another of a guy aiming a pistol in the house) from their proximity to photographs in the Deep South by Danny Lyon and Gordon Parks.

The Whitney curators had never hung anything in their new spaces until now so this first installation must be considered a trial run. I’m assuming that they will find a better way to group pictures in the future so the ensembles by the elevators don’t seem so forlorn and haphazard.

Less excusable is the shoddy hanging of Ansel Adams’ Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico in the chapter titled “Breaking the Prairie.” It has appeared in so many surveys of American art over the years that I would have no beef had the curators chosen to exclude it. But the decision to tuck it away in shadow, near a screening room, at the end of a string of landscape paintings, suggests either a WTF attitude toward straight photographs or a misguided understanding of Adams as a maker of beloved nature clichés, a contempt he does not deserve. If anything, he represents the combative values for a more progressive America burnished elsewhere in the show.

In a sense the entire installation is designed to validate the ethos of the 1993 Whitney Biennial. Even more than usual, it had incited a negative reaction because of the identity politics it reflected and endorsed, an anger and/or peevishness summarized in the infamous buttons by Daniel Joseph Martinez that read “I can’t imagine ever wanting to be white.”

The curators revisit that time under the chapter titled “Guarded View.” Included are photographs by Lorna Simpson (of her braided hair and back) and Catherine Opie (a self-portrait of her back, with self-inflicted wounds), a cloth doll mash-up by Mike Kelley, a self-portrait sculpture by Jimmie Durham, drawings by Raymond Pettibon, paintings by Sue Williams and Christopher Wool, prints by Kara Walker, and installations by Matthew Barney, Karen Kilimnik and Fred Wilson. (His headless mannequins dressed as museum guards gives the section its name.)

The group is centered around a 1992 sculpture by David Hammons. Made of rebar and hair, it manages to evoke an exploding hand grenade, a giant sci-fi mutant spider, and a head of unkempt dreadlocks. It’s a masterpiece, both frightening and hilarious. Perhaps the highlight of the show, it reinforces the simmering emotions more latent in the other pieces.

The wall text recalls the near-unanimous hatred the show incited from critics, although only one of them, Christopher Knight of the Los Angeles Times, is named. “Under the enthusiastic banner of opening up the institutional art world to expansive diversity,” he is quoted in the wall text as writing, “the Whitney has in fact perversely narrowed its scope to an almost excruciating degree. The result: Artistically, it’s awful.”

The curators pat themselves on the back by declaring that while “conservative critics of the 1993 Biennial lamented the loss of traditional aesthetics at the hands of ‘political correctness,’ these artists forged new and lasting understandings of beauty in relation to both bodies and art.”

As a friend pointed out to me, the Whitney fails to note that the lead hater in 1993 was Michael Kimmelman, then chief art critic of the New York Times, or that the current New York Times chief art critic, Roberta Smith, wrote at the time that the show “was less about the art of our time than about the times themselves.” As Kimmelman is now an arbiter of architecture, and thus more likely to pass judgment on the Whitney as a building, and as Smith is the most powerful art critic in any U.S. newspaper, it was disingenuous, if strategic in 2015, for the museum to outsource the 1993 opprobrium to California from New York. (For the record, Kimmelman pretty much loves the Renzo Piano’s building, primarily the interiors; and Smith gave thumbs up to America is Hard to See.)

Christopher Knight, and most of the other art critics who denounced the Biennial 22 years ago, would be shocked to hear themselves labeled (and mocked) as “conservative.” Bracing and vibrant as this chapter in the new Whitney may be in the retelling, it has been heavily edited to eliminate a lot of the junk displayed at the old Whitney in 1993.

The problem with “political correctness” then and now is twofold: the first is that when ethnicity, gender, sexual preference, and other social demographics become the criteria by which art is made, exhibited, and viewed, the audience can no longer tell if what they’re looking at is any good or, to paraphrase Ms. Smith in 1993, reflecting the times themselves.

Walking through “Course of Empire,”—the last chapter here, in that it takes into account Sept. 11, the wars in the Middle East, the election of Obama, and climate change—I could not help thinking that Abelardo Morell and An-My Lê, two photographers I believe to have been for decades among our finest, were included not because the Whitney curators genuinely admire them as artists—neither has ever had a show here—but because one is Cuban-American and the other Vietnamese-American.

By selecting them primarily because they make the Whitney (and American art production) look more ethnically diverse on the art world’s census forms, the curators are inadvertently slighting Lê and Morell as photographers. You’d never know from her print of an Operations Center at 29 Palms, hung here salon-style with other post-9/11 work, that Lê’s photographs are riddled with mixed feelings about America’s global military presence.

The second danger of the PC mentality that characterized the 1993 Biennial is more insidious. While pursuing admirable goals of bringing more voices into the museum that will question traditional “narratives,” whatever those might be, the new narrative itself often turns out to be just as predictable and safe, and even more wary of contradiction or causing insult.

No matter how crudely or obviously questions about certain issues (race, gender, sexual preference, social oppression, consumerism) are phrased, so long as the artist is perceived to be rattling our cages, he or she is deemed to be doing or “saying” something important.

Any critic who dares to believe that curators should not be narrowing the scope of the art they champion to reflect mainly those views of embattled minorities should not automatically be branded a “conservative.” Only in the perverse, topsy-turvy politics of contemporary art, circa 1993, could Hughes, Knight, Kimmelman, or Smith be regarded as anything but obstreperous liberals.

The art world complacently assumes that everyone leans left on social and economic issues. In truth, most of us probably do, except perhaps the 1% who actually pay for the buildings, the insurance, the security guards, the HVAC, the temporary exhibitions, and the art. The avant-garde, rounded up every two years by the Whitney curators, has to pretend they don’t rely on the largesse of the wealthy, a class of men and women their Frankfurt School art theory tells them they should despise. This illusion may be harder still to maintain in a museum that cost (with land) in excess of half-a-billion dollars.

Is it commendable that Lê and Morell are on the walls? Of course. Would it be better if they were not? Of course not. The inclusion of so many artists seldom featured in museums or in the art history textbooks is refreshing. The epic story of 20th-century American art realized by De Salvo and her team is more comprehensive and persuasive than the one by Hughes. The interplay of video and photography in the chapter titled “Learn Where the Meat Comes From” (named after Suzanne Lacy’s send-up of Julia Child) is frisky and the roster of names gives opportunity to lesser-knowns (Hermine Freed, Asco, Ulysses Jenkins) and the usual suspects (Chris Burden, Eleanor Antin, Vito Acconci, Joan Jonas.) A mood of humor and aimless questioning is far more pervasive in the galleries than any closed doctrinaire interpretation of what—or whom—art is supposed to be for.

But except for Nan Goldin, none of the photographs are exhibited with the same conviction or mischief-making glee that one finds in, say, the display of Hammons or Wilson or Barbara Kruger or Rachel Harrison. Even though the Whitney’s director, Adam Weinberg, trained at the Visual Studies Workshop and did photography exhibitions when he directed the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Whitney curators have traditionally viewed photography as an afterthought. There’s a reason they didn’t collect it until 1990. The museum has never given any photographic artist, except Goldin and Sherman, the respect they routinely command in departments at MoMA and the Met, and that goes double for the Biennials.

Were the curators not so straitened and conservative in their understanding of what medium has been, and is becoming in the digital age, American photography might not be so hard to see in the galleries of America is Hard to See.

If the curators had taken the time or shown some imagination this promising new day for the museum might have found incongruous pairings of art, akin to that first room in Modern Starts, where a Rineke Dijkstra photograph of a teenaged girl, wearing a cheap swimsuit and a pained smile, stood awkwardly on a beach next to a painting of an unheroic Cezanne male bather. I found no such happy coincidences on the walls here, and I don’t think that’s too much to have hoped for.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are , of course, no posted prices. As such, we have omitted the usual discussion of primary and secondary market prices usually found here.

What bothers me on this very lengthy review, is that the reviewer basically wants to see the same names and pictures in each and every (American) show and criticizes the Institution, this time the Whitney for not showcasing the same photographic heroes and telling them they were wrong to not include them.

I have been collecting photography for about 40 years and do have the images, the reviewer misses in this show, but I do love the show and I am not missing a single one of these images. I want to congratulate the curatorial staff with their excellent choices and very much liked the way in which a large variety of photographs are integrated in the story the curators are trying to tell about collecting at the Whitney.

So there are no Robert Franks and no Stieglitz etc etc. so what!

I do not judge the quality of a museum collection collection about what is missing, but on the quality that is shown.

This show is not about

I hope that I didn’t focus too much on the names of those who were missing from the show. I tried to dispose of that issue in a couple of paragraphs. Like you, I don’t want to see the same names in every history.

I was more bothered by the rather shabby treatment given to some photographers who were included (Stieglitz, both A. and R. Adams, Eggleston) rather than by the absence of other classical figures. After all, plenty of established painters and sculptures you would expect to be here are missing (Dan Flavin, Eric Fischl, for starters.)

My piece was about the benign neglect that the Whitney has demonstrated over the years toward photos. I don’t want to knock them too much because they have only been collecting them since 1990. But that in itself says something about how they value the medium, a disregard reflected in the space it is given over the years in Biennials. The museum’s collecting philosophy prides itself on being “untraditional” (Nauman and Piper rather than, say, Sinsabaugh and R. Adams) but it ends up being a much narrower and conservative view of what photography has been and can do than is found in places like MoMA or SFMoMA or the AIC, or even the Met, where photos of many kinds have been treated with curatorial reverence.

What I should also have mentioned is that the old Whitney showed photographs in small print galleries. In this installation, other than Nan Goldin who has a room to herself,

photos were in large spaces with other, often more overwhelming works. The new Whitney is fabulous for big painting and it’s the most beautiful place for sculpture of any museum in New York. It has yet to prove it can exhibit photography with the same sensitivity.

I should have given AIHTS more credit for avoiding contemporary art cliches. It was terrific that they showed early small C. Shermans rather than more recent big ones found in so many museums of late, although a few big photos by someone would have helped. That’s my main gripe: Nowhere did I find my view of photography altered or expanded by the show.