JTF (just the facts): A total of 14 works, variously framed/unframed and hung against white walls in the main gallery space, the entry area, and the back office room. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

Herbarium

- 4 archival pigment prints, 2023, sized roughly 40×32 inches, in editions of 6+2AP

- 3 archival pigment prints, 2023, sized roughly 21×17 inches, in editions of 6+2AP

Chromotaxy

- 1 archival pigment print, 2023, sized roughly 21×17 inches, in an edition of 6+2AP

- 1 archival pigment print, 2023, sized roughly 40×32 inches, in an edition of 6+2AP

- 2 archival pigment prints, 2023, sized roughly 50×39 inches, in editions of 5+2AP

- 1 set of 94 archival pigment prints, 2023/2024, each sized roughly 10×12 inches, in an edition of 3+1AP

- 1 set of 18 archival pigment prints, 2023, each sized roughly 11×8 inches, in an edition of 3+1AP

(portrait) 1 archival pigment print, 2023, sized roughly 21×17 inches, in an edition of 6+2AP

Comments/Context: For a casual poetry fan, having a few volumes of poems or a fuller published collection of a favorite poet’s works on a nearby bookshelf, to be dipped into from time to time, is likely enough to satisfy intermittent poetic urges. But for more committed readers, even a deep dive into the complete works by a particular writer only scratches the surface of their interest, soon to be followed by histories, biographies, letters, critical essays, and other ephemera that might help fill in the backstory to the poet and his or her life. By probing this rich trove of additional information, a fuller understanding of the intentions, inspirations, and context behind the individual poems is potentially possible, as well as a kind of broader communion with the poet, offering tantalizing answers to who the poet was, what his or her life was like, and how he or she thought.

As one of the most beloved of America’s 19th century poets, it’s not at all surprising that Emily Dickinson would be a touchstone for plenty of writers and artists of all kinds, even more than a century after her death. Dickinson’s poems are filled with references to flowers and plants, and what the artistic duo of Amanda Marchand and Leah Sobsey discovered as they began to dig into Dickinson’s history further was that this wasn’t an accident – it turns out that Dickinson was a passionate amateur botanist. Starting as a child, she helped her family in their large garden, and when she entered school (and later university), her botanical interest was amplified further by the support and encouragement of her teachers there. This led to the habit of gathering, growing, sorting, and classifying the flowers and plants around her home in Amherst, Massachusetts, and ultimately arranging the pressed specimens on pages in a bound scrapbook album. Dickinson’s Herbarium (made in the late 1830s and early 1840s, and now held in the Houghton Library at Harvard) runs to some 66 pages, with over 400 individual specimens carefully placed with identifying titles into precise single page compositions. As a historical object, it is both astonishingly in-depth and scientific, while also offering a distinct echo of the aesthetic control and fragile beauty found in Dickinson’s poems.

Inspired by Dickinson’s Herbarium, and locked down in their respective homes (in Quebec and North Carolina) by the pandemic, Marchand and Sobsey embarked on an ambitious project to recreate the botanical sampler by growing all the plants and flowers depicted there. And over a period of three years, they did just that, using scans of the individual pages from the Harvard website (here) as their guide. While there was likely some completionist satisfaction to be had by the artistic duo when they checked off the last specimens on the long list, they are of course artists, and so their bountiful gardens then became the starting point for their own photographic re-interpretations of Dickinson, her poetry, her Herbarium, and the many plants it included.

Perhaps the most obvious or literal approach Marchand and Sobsey might have taken would have been to use their own plants and rebuild the herbarium page by page with new 21st century specimens, which is exactly what they didn’t do. Instead, they took a different path, that likely felt more physical, more scientific, and more artistically romantic. Marchard and Sobsey decided to embrace the antique anthotype process, a nearby light-based relative of the photogram and the cyanotype. Anthotypes were being made at roughly the same time Dickinson was living and working (several most famously by their discoverer Sir John Herschel), and had the advantage of being derived from plants. The emulsion is made from the plant itself, with petals, leaves, and other plant materials ground up and then diluted into a liquid pigment, which is ultimately spread on paper; the “printing” takes place by placing objects on the coated paper and exposing them to the sun, which bleaches the plant emulsion over time, changing the color and creating the photographic effect.

So to recreate their own version of Dickinson’s Herbarium, the artists developed sixty-six individual pigments from their plants, one for each of the pages of the original album, often keyed to the notable specimens on that page. Using the scans of Dickinson’s pages as the visual raw material, they made new anthotypes of all the pages, now in the actual colors of marigolds, impatiens, snapdragons, pansies, and other plants and flowers. The show begins with a soft pink image made with red salvia (plate 12), and continues around the room in shades of yellow, light brown, blue, and purple, each plate re-imagined in tactile silhouetted colors. Conceptually, Marchand and Sobsey are following along in the steps of artists like Matthew Brandt (and others), who have made photographs using techniques that embed elements of the subject in the actual photographic process, like using river water to develop an image of that same river, or sticky black tar as part of the emulsion capturing images of tar pits. Marchand and Sobsey travel similar roads, and their results are consistently soft and almost ephemeral, like the visual traces of the original plants (and Dickinson’s hand) re-invigorated by nature once again.

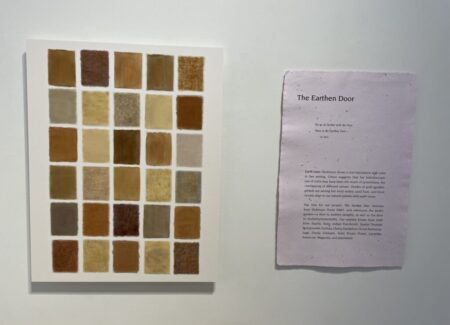

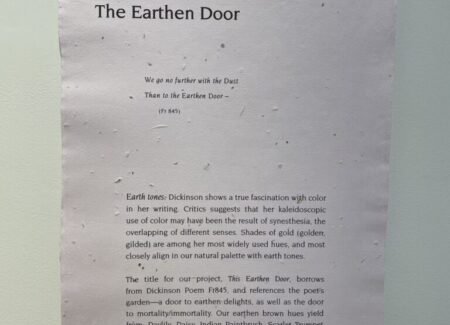

Armed with their Dickinsonian pigments, the two artists have also crafted a series of pigment-only compositions, called “chromotaxys”. Using either scientific information or textual cues pulled from Dickinson’s poems as organizing principles, the works feature typological blocked panels of pigment, each work conceptually held together by a common theme and titled with a first line from one of Dickinson’s poems (as explained in printed wall panels). Most straightforward are color stories like whites or earth tones, which group the individual floral pigments into narrower ranges of similar hues. Taking a more scientific bent, the largest work brings together more than ninety different colors in one wall filling array, all from plants that self-fertilize; another nearby group selects only the pigments from plants that produce edible flowers. A circular arrangement reinforces the idea of the natural cycle of the seasons, with the color blocks sequenced by the time when the plants bloom. And a more effusively haphazard arrangement refers to various kinds of love, as found in both Dickinson’s poems and in the particular flowers as traditional symbols for those emotions.

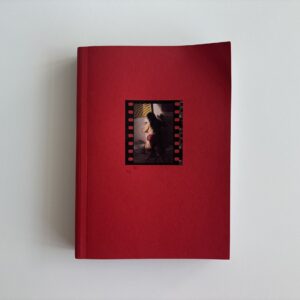

Seen together, the two distinct projects (and one silhouetted portrait of the poet at age 14, executed as a red daylily anthotype) thoughtfully leverage a lesser known facet of Dickinson’s legacy, and transform it into new visual forms. Both Dickinson’s original botanical efforts and Marchand and Sobsey’s subsequent artistic interpretations feel richly obsessive, painstaking, and meticulous, reveling in details and nuances that then become the raw material of a poem or a subtly-colored artwork. In this way, the two contemporary artists activate their reverence for Dickinson and physically make it their own, jumping across time by actually getting their hands dirty.

Collector’s POV: The single works in this show are priced between $3500 and $9500, while the multi-print sets are priced at $9500 and $35000. The joint work of Marchand and Sobsey has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.