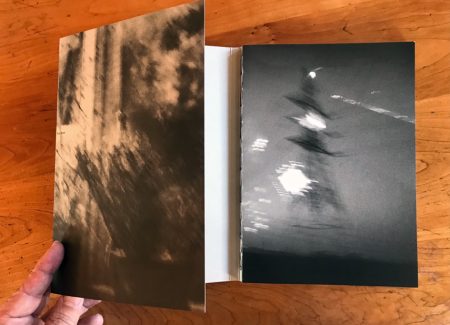

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2021 by Photo Editions (here). Swiss bound softcover with folding overleafs, 24 x 17 cm., 108 pages, with 57 monochrome reproductions. Designed by Tom Booth-Woodger. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: In thinking about Alison McCauley’s photos, it’s helpful to start at the beginning. Since childhood, her life has been peripatetic. Her father designed hydroelectric dams, a job which took him and the family to projects all over the world. They moved in serial fashion, a few years here, a few years there, to Wales, Singapore, and Brazil, among other places. McCauley carries an English passport, but she has never spent much time in that country, nor more than a few years in any other one. Her vantage point has shifted frequently, and she’s become a careful observer out of necessity.

The globetrotting lifestyle had its benefits—she acquired multiple languages and an openness to new people and experiences—but also its detractions. At each new location, she found herself starting from scratch with a new school, new friends, and routines. It was hard to form lasting bonds. “As someone who has always moved around, I am very interested in the idea of belonging to a country or a community. This is a feeling that I’ve never had,” she explains on her website. The opposite of belonging might be something like the German term fernweh. But there is no direct English equivalent, just a vague sense of rootlessness.

This feeling has remained with McCauley into adulthood. She’s enjoyed a stable life in Geneva for several years now, her longest period in any single place. It’s a beautiful city with every amenity. But it does not feel like home. She visits Cannes each summer, as well as other European destinations (at least before the pandemic), but they too can’t offer a permanent fix. In any case it may all be temporary. In a curious full-circle twist, her husband’s current job involves a degree of globetrotting. So they may be moving again in the foreseeable future. Where or when is not clear.

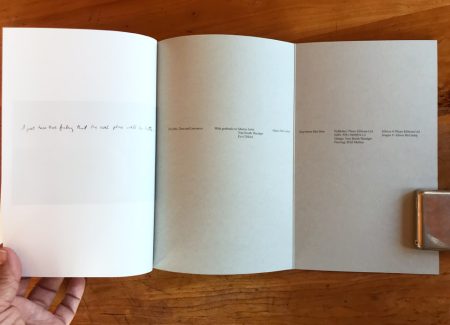

In the meantime, there is always photography. McCauley has been a devoted practitioner since the mid-2000s, after an initial fling with painting. Her efforts have recently culminated in a debut monograph Anywhere But Here, a book which crystalizes the peripatetic mindset while shirking any documentary impulse. “These images attempt to express the restless feeling that the place I’m in isn’t where I should be,” explains McCauley. “I just have this feeling that the next place will be better.” This last sentence is the handwritten coda on the book’s final page. It’s delivered in a spirit of self affirmation and, positioned at the close, feels forward looking. A plaintive declaration by someone’s who’s never felt quite at home, and who may be moving to greener pastures.

There are 57 monochrome pictures in the book. Their general timeline is noted—roughly 2008 to the present—but I am hard pressed to identity any of the original locations. This deliberate disorientation is a harder camera trick than it might seem. Photographs divulge information by nature. They just can’t help it, and it requires conscious restraint to muzzle them. Despite a photographer’s best intentions, a stray skyline, sign, building, or hairstyle can communicate place and time.

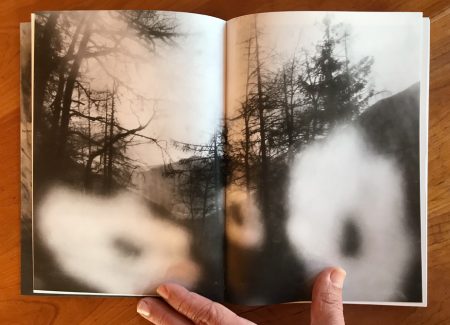

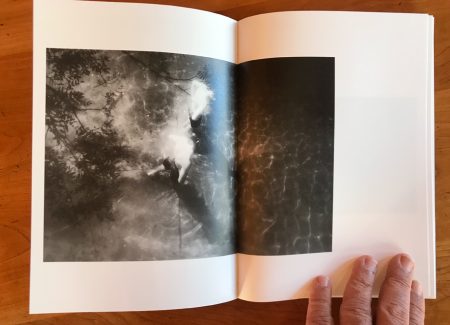

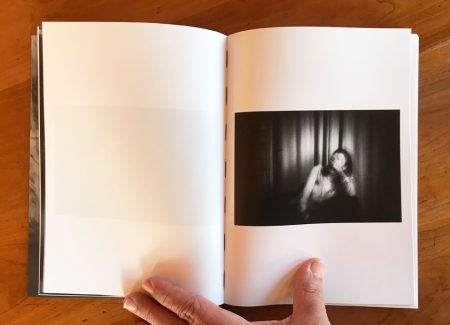

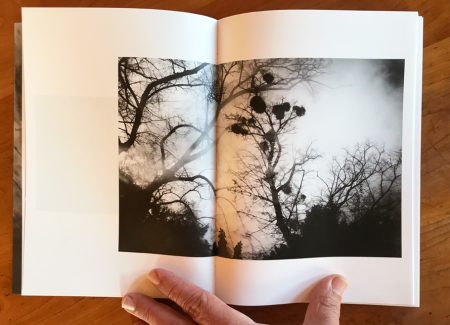

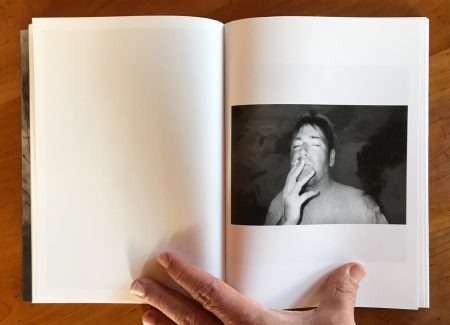

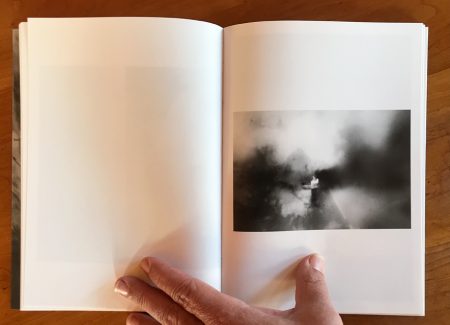

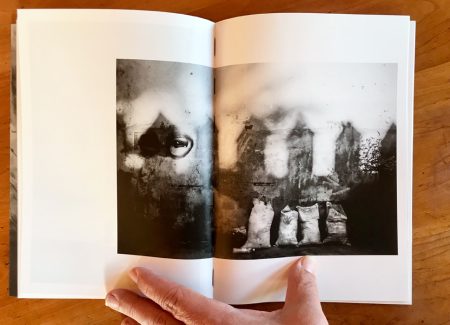

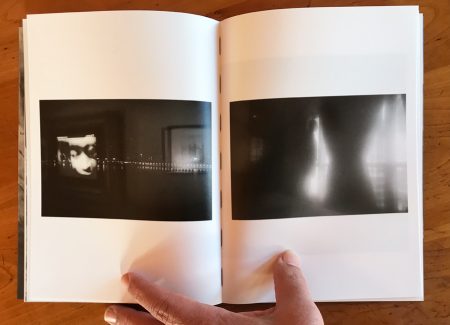

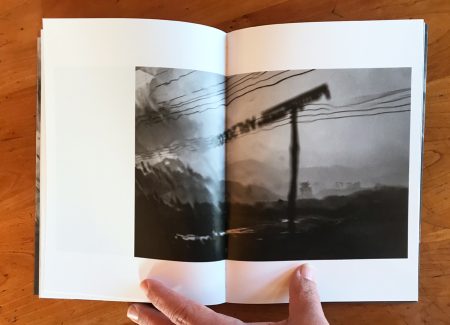

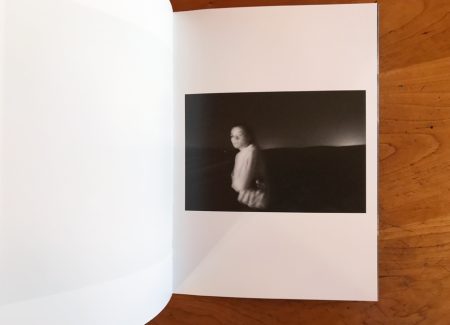

McCauley is keenly aware of the risk, and has taken measures to erase most clues of provenance. A figure shuddering against a dim window might be in Geneva…or Bali? Or Japan? Light poles strung in a vacant lot might be anywhere as well. Anywhere but here, that is. A photograph of burlap sacks against a wall seems strangely superimposed with fence posts and and eyeball. A couch below two bright sconces hints vaguely at hotel rooms and jet setting. Other pictures show couples swimming, figures walking, blurred watermarks, and clouds, perhaps seen from a plane window. It’s all rather dreamy, and dreams resist logic. Instead McCauley’s is a rootless netherworld, hard to pin down or explain.

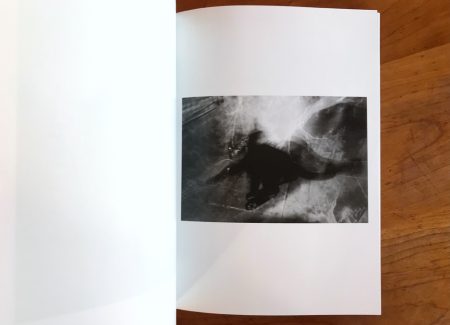

It goes without saying that none of the photos are captioned. “The geographical and temporal reference points in the photographs are blurred,” she says, “because the work isn’t about the location or time, but about a state-of-mind. There’s no real beginning and I don’t think there will be an end. The work comes from reality, but it’s a reality that’s distorted by subjectivity. It’s an expression of my state of mind during these restless off-moments.” Hmm. Her pictures may be fuzzy, but this declaration is so clear and direct that it might be a futurist manifesto. Perhaps a hint of the new world, post-nation, comprised of global citizens hopping from country to country? Or merely the stray thoughts of an outside observer.

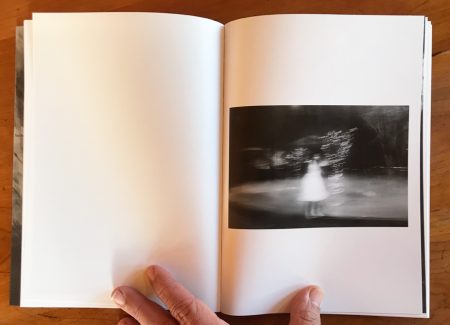

The book’s mood and process are exemplified in the cover photo. As recounted in a recent series of Instagram posts, this was one of the initial exposures in the project, shot in 2008 in Geneva. After an otherwise nondescript day hunting photos outside, McCauley slipped into a coffee shop to warm up and recalibrate. She was experimenting with a compact camera at the time. Without much forethought, she aimed it out the window at passersby. Dim lighting, motion blur, and condensation added murky artifacts. She liked them quite a bit. They seemed to lead in a new direction, but its shape was not yet clear. After about forty minutes of shooting, she filed the pictures in a desktop folder. “Later when I looked through the images,” she explains. “I realized I had made a breakthrough. For the very first time I had taken images that seemed to express the restlessness and melancholy that I felt at that time.”

Two of the photos from that day seeded the series Anywhere But Here, and one became the book’s cover. Cropped tightly on a woman’s face, with stark contrast and blurred effects, it is impressionistic beyond recognition. We can see the woman a little better in the uncropped version which appears (flipped horizontally) early in the book. More of her torso is visible, along with a bit of background. But still, it’s not much to go on. The woman is long gone now. But if she were to somehow stumble on this book, with her muddled visage on its cover, it’s unlikely she would recognize herself. Nor would most other people shown in these pages.

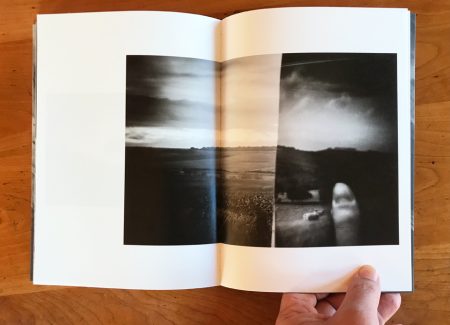

After those initial exposures McCauley came to master that early compact camera, as well as other visual effects. She spent the next fourteen years perfecting them, or perhaps imperfecting is a better description. “In photography and most other art forms, rules should be learned and then dismissed,” she writes. A rule of sorts, but we’ll let it slide. Anyway, you get the idea. Anywhere But Here shuns orthodoxy, instead taking an inclusive approach to photo technique. McCauley employs an endless bag of tricks, tools, and obfuscations: double exposure, analog/digital combinations, slow shutter, plastic lens, scan mishaps, flash, Polaroid, reflections, and more. One of her go-to moves—perhaps a byproduct of her girlhood near dams?—is water effects. She uses condensation, rain, fog, and lens coatings, with dexterity. There are even a few “straight” photos in the mix for good measure, looking rather staid amid the surrounding mayhem. She is generally coy about specific process details, but suffice to say she enjoys alchemy, misdirection, and dislocation. All can be viewed as natural creative manifestations of her semi-nomadic lifestyle.

Before connecting with Photo Editions, McCauley channeled this raw experimental energy into home-made books. She made several over roughly a decade, sequenced with perhaps twenty photos at a time, typically self-published in small editions, of twenty or perhaps up to fifty at the most. These hand-made books served as rough models when planning Anywhere But Here with designer Tom Booth-Woodger. Both agreed that it should have the same DIY spark and hands-on tactile quality.

To a large extent they’ve succeeded. Anywhere But Here’s modest stature was a nod to her early works. At 24 x 17 centimeters, it’s not quite as small as those postcard-sized books, but still diminutive enough to feel intimate and portable. ABH might fit into a large pocket or handbag, or perhaps atop suitcased clothing during the next life move. The sizing and layout of photos on the page has a transitory nature also, switching patterns with breezy efficiency. The softbound cover with pull out flaps and Swiss binding all lend ABH an organic feeling. With its spine exposed, readers can peer right into the book’s guts, just as with her hand-made books. The pages lay flat, allowing the binding threads to surface here and there. All of the book’s text (there isn’t much) is tucked into the rear cover, as it might be in a small monograph hand-crafted at the kitchen table. In short, a lot of thought has gone into production to create a monograph with intimate, personal feeling.

Where McCauley winds up next is uncertain. It won’t be here (Geneva), but the exact location is TBD. For now, she’s put down a marker with this monograph. Anywhere But Here should live a stable existence in photoland for some time.

Collector’s POV: Alison McCauley does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via her website (linked in the sidebar).

Hey Blake, I love Alison’s work, and own one of her hand made books. Just wanted to clarify (although it’s in the stats at the top) that the book is 24 by 17 centimeters, not inches as stated in the text