JTF (just the facts): A total 33 black and white photographs, framed in light wood and matted, and hung against white walls in the back gallery space and the connecting hallway. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 1953 and c1965, in a mix of vintage and modern prints. The modern prints are sized roughly 15×11 inches (or reverse) and are available in editions of 8; the vintage prints are sized roughly 5×4 inches (or reverse), and no edition information was provided for these prints. The show was curated by Vasco Szinetar. A small companion booklet has been produced by the gallery, with an essay by Luis Pérez-Oramas. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Flip through any family album full of photographs and it quickly becomes clear that we have been trained from a very early age to work together with whoever is behind the camera, adopting poses and smiles appropriate to the occasion or situation. It’s almost as if we expect to collaborate, as if the making of the picture is a process that we intuitively understand functions best when both sides are actively participating.

The history of photography as an artistic medium has, of course, been consistently populated by partnerships and working relationships. Whether they are models, muses, performers, and portrait sitters or spouses, partners, lovers, and friends, all of these people are (or become) collaborators of one kind or another. Many of these collaborations are filled with obvious warmth and affection, even passion; others are populated with willing engagement and purposeful cooperation; and still others resonate with friction and tension, changing the dynamics of the interaction. Each human interchange offers its own set of forces and emotions, and those influences often find their way into the resulting pictures.

And it is this innate tendency toward collaboration makes Alfredo Cortina’s photographs of his partner Elizabeth Schön so puzzlingly unexpected. Cortina was a radio and television director and executive in Venezuela in the 1950s and 1960s, who spent part of his life inside a group of intellectuals and avant-garde artists. He also made photographs around Caracas, including landscapes and still lifes of the traditional ways of life found nearby, and after his death in 1988, his work was lodged in an archive and largely unknown until it was shown in the 2012 Bienal de São Paulo. Among Cortina’s most notable pictures was an extended series of images of Schön, where the poet is posed against a wide range of landscapes and settings.

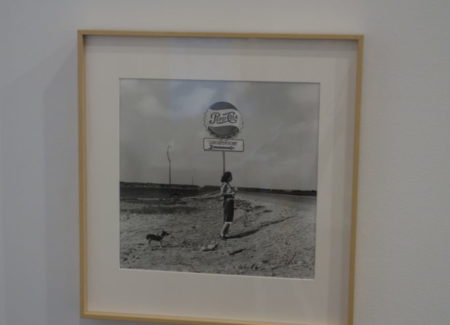

At first glance, these images seem to follow a typical vernacular photography pattern of a spouse posed in front of various destinations visited during a lifetime – at the beach and the seaside, in gardens and on hikes, on city streets and sidewalks, at construction sites, and on road trips around the countryside – and if this was the case, they might be important to the couple, but entirely forgettable in terms of the larger arc of the medium. But what’s different here is Schön’s persona. She doesn’t smile, she doesn’t wave, she doesn’t gesture in any way really, she simply stands in the landscape, largely with a neutral expression, and across dozens of pictures and more than a decade, her approach as a subject or sitter doesn’t deviate.

Her persistent indifference is perplexing. While we can draw some information and perhaps even some conclusions about where she is, she offers us nothing about what she is doing or why she is there. In this sense she upends the idea of engaged portraiture – she reveals nothing, she doesn’t collaborate, she looks back at us, or Cortina, or out into the distance, always alone, any tension in the scene drained away entirely, to the point of emptiness. Even the most ordinary of set ups (near a billboard, or walking along a dirt road, or emerging from a doorway) fails to deliver any purpose or intention. She is both cooperating and not cooperating, and while she is physically present, she is still very much anonymous, which brings us back to examining the bandshell, or the steel tower, or the backdrop of jungle found in the composition in the hopes of discovering a sliver of narrative to fit the scene provided, which of course we can invent, but is never really overtly provided.

This kind of deliberate neutrality has been explored in contemporary photography, in everything from Thomas Ruff’s deadpan headshots to Carrie Mae Weems’ back-turned presence at various singular locations and monuments, but Cortina’s obsessive archive was made decades earlier, before this kind of conceptual framework making was commonplace. So these pictures take on the feeling of an outlier, or a precursor, or an odd form of genius. What’s fascinating is that as Schön stands by a hotel swimming pool, or in the middle of stream, or on some railroad tracks, she seems to quietly assert control over the space, recasting the landscape around her. Her stoic presence would make an intriguing foil for Cindy Sherman’s untitled film stills, where Sherman’s staged roles and moods take cues from their settings and Schön’s mute confidence seems to nullify her surroundings.

So while we can’t easily re-insert Cortina’s images back into a historical pattern of influence or conceptual thought, we can retroactively recognize their surprising innovation. These images might appear to be humble everyday tourist snapshots, but they have a persistent sense of understated but radical disregard, as if the conventions of photographic portraiture were somehow unimportant to what these two wanted to accomplish. As a group, the photographs offer early evidence of the roots of ideas that would come along later, like an isolated but parallel artistic discovery.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced as follows: the vintage prints are $6000 each, while the modern prints are $3800 each. Cortina’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

A fine review as usual with one important omission. There seems to me to be a clear relationship between these images and Harry Callahan’s public portraits of his wife Eleanor. Callahan’s portraits are more overly formal and we typically see Eleanor from a greater distance. Still they are conceptually distinct from the history of portraits like Cortina’s and done around the same time. Consequently very relevant to the points you discuss.