JTF (just the facts): Published in 2024 by Folium (here). Hardcover, 176mm x 225mm, 96 pages, with 79 black-and-white reproductions. Includes a printed bookmark, an introduction by Alan Huck, and a conversation between Eugenie Shinkle and the artist. In an edition of 200 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

The Night and the First Sculpture also comes in a special edition (here), which includes a signed print, a signed book, and a wooden box.

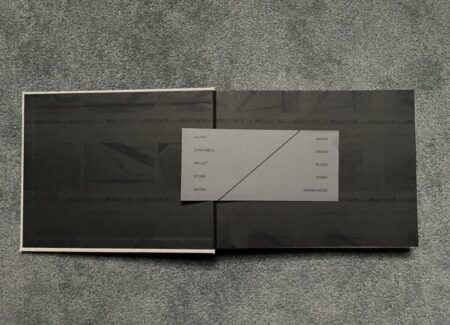

Comments/Context: When you open Alexander Mourant’s photobook The Night and the First Sculpture for the first time, a loose bookmark printed on grey cardstock falls out. On one side, it declares the card to be “The Artist’s Lexicon”, and on the other, it sets up two arrays of words divided by an angled slash – glass, concrete, pallet, stone, and wood on the left, and image, space, place, story, and knowledge on the right. Perhaps there is a one-to-one definitional alignment to the divided word pairings, or maybe just a broader conceptual split between the materials and what they might represent, but either way, it’s clear that Mourant has limited himself to a small number of artistic variables, that he has intentionally set out for us before we see any of his photographs. This succinctly introduces us to an intellectually-rich exercise in constrained artistic problem solving, where he intends to use the things on the left to explore the things on the right.

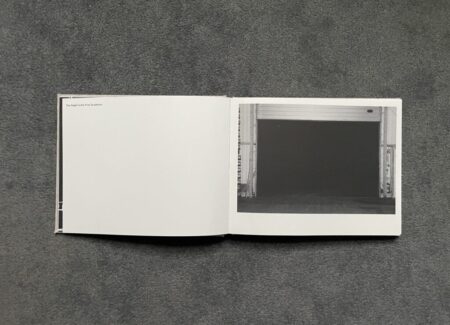

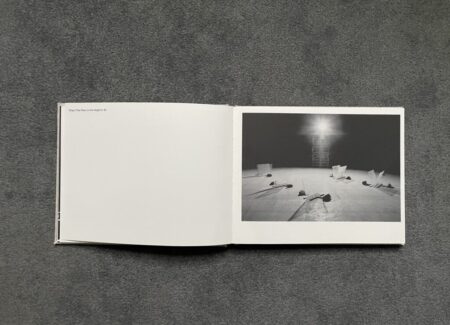

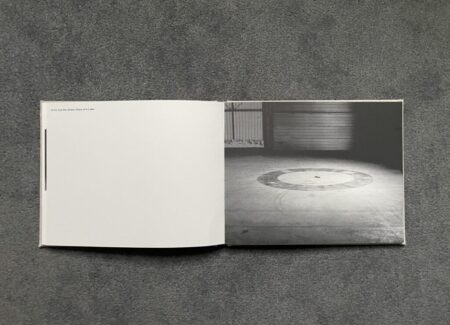

The first image in the photobook sets the scene for Mourant’s performative experiments – a dark building (at his family’s farm) with roll down garage doors. It’s a picture that would have satisfied Lewis Baltz, with its strict geometries and modest industrial details, but for Mourant, the space represents the fixed playing field for his artistic exploits, like an empty theater before the players come on stage.

In a sense, Mourant’s farm building is the opposite of the kind of perfect white cube in which we normally experience sculpture, or art more generally. It’s nighttime dark, with a concrete floor, illuminated by a few spotlights that pierce the enveloping black, and populated with the humble materials and everyday tools available inside such a place. It’s easy to imagine Mourant working alone, through the quiet of the night, building, rebuilding, and then disassembling his ephemeral creations, all without disturbing the normal daytime rhythms of the farm. It’s as if the artistic magic happens when no one is looking, leaving the photographs as the only evidence of what has taken place.

To say that Mourant’s photographs are documents is only partially correct. Of course, they document what was in front of the camera when he clicked the shutter, thereby memorializing the particular arrangement of materials (and people, when the artist is present) laid out on the vast concrete floor. But the camera here is more of a collaborator or participant that in most photographic documents of sculpture or performance; it didn’t come later to witness what was occurring, but instead was a part of the process from the very beginning. Conceptually, it seems Mourant was thinking about “how sculptures perform to the camera” and then crafting setups where the camera is already in the right place at the right time.

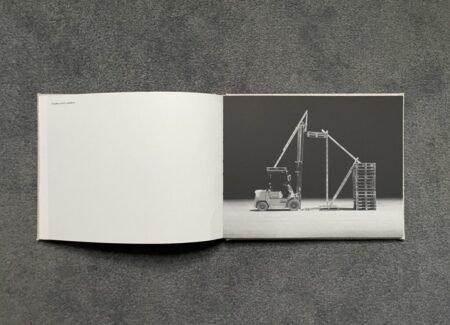

The ostensible subject matter of Mourant’s photographs could hardly be more forgettable: lots of wooden pallets, square sheets of greenhouse glass, several 2x4s, a few rocks, some dowels, a rope, a wooden chair, a grid of rebar, and a few useful tools, like ladders, a wheelbarrow, and a forklift. Each image is a reconfiguration of these found materials into a scene which is then photographed. For the most part, we don’t see the artist’s activity or physical labor, leaving the lifting, moving, balancing, and arranging generally off screen (with a couple of exceptions). But even though we only see the final product of that effort, the pictures feel resolutely process-driven, the making and invention activity seemingly floating invisibly in the air.

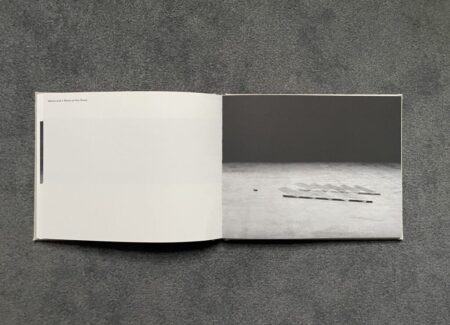

Several of Mourant’s images offer narrative allusions, in the form of a descriptive title that makes the associated arrangement of objects take on a particular visual interpretation. In this way, v-shaped pairings of glass sheets and rocks on the concrete floor become ships on the ocean, the up-and-down movement of glass plates evokes a train carriage, layered stacks of glass alternately become waves heading for a rock on the shore and an angled roofline covered in tiles, and a single broken shard of glass staged in the middle of a circle of glass plates is transformed into the raised fin of an aquatic creature in a lake. There is a clever “a-ha” playfulness to each of these constructions, with a possible story teased out of the elemental formal relationships of the materials.

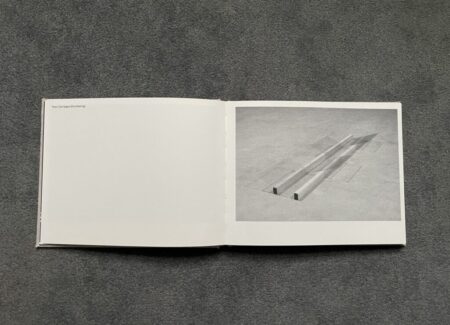

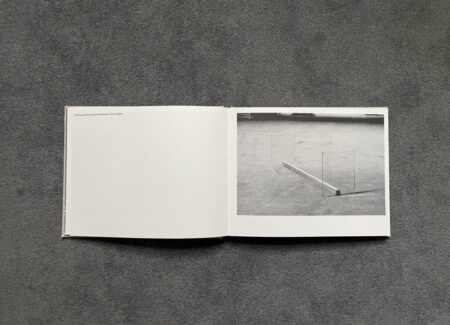

In other photographs, Mourant makes a more explicit connection between the sheets of glass and physical images, creating photoconceptual setups that use the spatial relationships to “measure” the properties of the images. One arrangement seems to calculate the distance between two images using the length of a 2×4. Another captures the “weight” of an image suspended between two pallets, while a third balances an image atop a triangle point of two arms (which are again 2x4s). And “The Life and Death of Images” finds the glass sheet now broken and firmly trapped in the jaws of a vise.

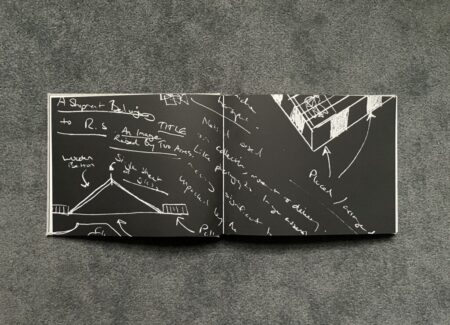

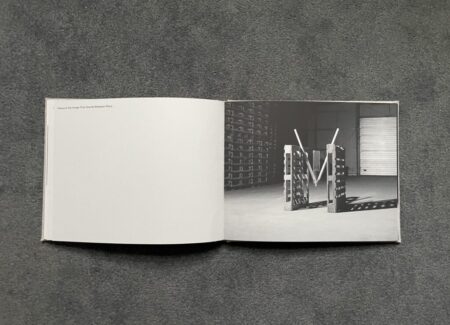

This inwardly-focused imagery about imagery pushes further toward overt references to art history in “A Shipment Belonging to R.S.”, where the initials refer to Robert Smithson. In particular, Mourant is referencing an unrealized 1969 installation Smithson had planned for Miami, which was to include a massive pile of fractured glass placed on a small island (a smaller variant of this idea can be seen installed at the Dia:Beacon here). Mourant’s work envisions an earlier stage in the project, where glass sheets have been boxed up, ready for shipment to their final location. Mourant is clearly aware of the histories of Land Art and the Earthworks movements, and how they conceptually relate to what he is doing in his farm garage; there are also clear echoes of the Arte Povera movement and its use of simple materials.

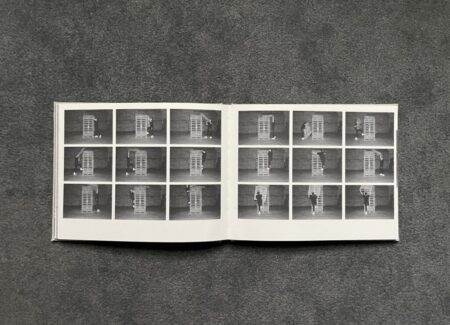

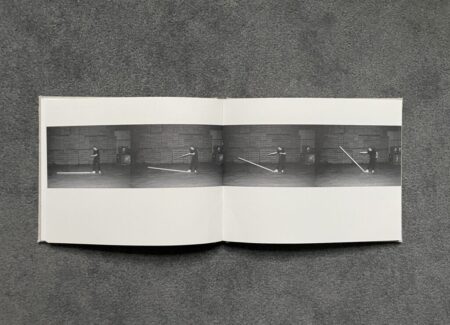

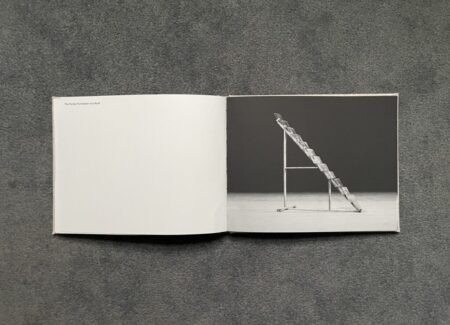

Several other works edge more closely toward performance, with sequential images that capture the building or activation of a sculptural structure, almost in the manner of Robin Rhode. One series finds Mourant stacking up wooden pallets one after another, until his stack is so tall that he has to climb out of the frame to sit on top. Another series documents Mourant pulling a 2×4 up and down with a rope, in a geometric manner reminiscent of some of Japanese photoconceptualists of the 1970s. Still other works seem to imply physcial interaction, but don’t actually show it; the image “Snakes and Ladders” seems designed for acrobatic climbing and traversing (just like the children’s game it references), however unstable the temporary construction may be.

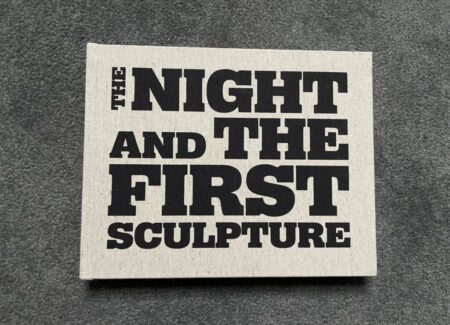

In terms of design and construction, The Night and the First Sculpture matches its content well. The linen-wrapped cover lines up with the artist’s appreciation for modest materials, and a bold black font is used to deliver the title (with the artist’s name placed on the back), echoing the nocturnal art making found inside. Shadowy black-on-black endpapers offer snippets of contact sheets, while intermittent pages of sketches similarly attest to the process-centrism of the artistic thinking going on. Inside, the pages are thick and tactile, with individual works each given their own spread (or spreads). Overall, it’s a book that encourages and rewards physical touch.

What I like best about this body of work is its easy going obsessiveness – Mourant is clearly a thorough artistic thinker, and his farm-studio process seems to have engrossed him to point of singular attention. He refers to the whole exercise as a “cosmic dance with the materials and making”, which doesn’t seem so far from the plausible truth. Within his own self-imposed boundaries, Mourant has discovered a universe of photographic possibility, and crafted a photobook that recreates that constrained artistic energy with engaging fidelity.

Collector’s POV: Alexander Mourant does not appear to have consistent gallery representation at this time. As a result, interested collectors should likely follow up directly with the artist via his website (linked in the sidebar).