JTF (just the facts): Published by the Hall Family Foundation in association with the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, the catalog accompanies an exhibition of the same name at NAMA from July 25, 2014-January 11, 2015 (here). Hardcover (11 ¼ x 11 ¼ inches), 180 pages, 275 duotone photographic reproduction, with a foreword by Julián Zugazagoitia and a preface by Keith F. Davis. Distributed by Yale University Press. $60 (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Until about 25 years ago, Alexander Gardner’s standing among photography historians rested mainly on his acumen as a businessman and publisher. Atop his resume were his actions during the Civil War. In 1858, he and his brother James opened a branch of Mathew Brady’s operations in Washington, D.C. and in 1863 set up a competing gallery of their own. His energetic skills on the fields of battle during those years, however, were overshadowed by that of his sometime companion, the much younger Timothy O’Sullivan. The duo worked amid the living and the dead at Antietam, Gettysburg, the Siege of Petersburg, and other bloodbaths.

By war’s end at Appomattox, Gardner was 43 and had been photographing for almost 15 years. He would by then have observed that commercial success in the still novel medium was governed by establishing the right contacts as much as by artistry. His friend Allan Pinkerton had opened barred doors for him with the U.S. government, insider access that may explain why, in April 1865, Gardner was the only photographer to portray Lincoln’s assassins and their execution—an event some historians have called the birth of photojournalism. He would have learned from Brady the value of self-promotion and the risks of entrepreneurship. Even if Gardner’s Photographic Sketchbook of the War proved to be a financial bust—like many of Brady’s schemes—the ambitious 1866 publication did not follow his former employer’s credit-hogging example. Instead, Gardner scrupulously listed the names of those individuals responsible for taking each image in the two volumes.

This narrow view of Gardner’s career was enlarged in 1991 with publication of D. Mark Katz’s Witness to an Era: The Life and Photographs of Alexander Gardner and with Brooks Johnson’s exhibition and catalog for the Chrysler Museum, An Enduring Interest: Photographs of Alexander Gardner. Both researchers emphasized the admirable breadth of Gardner’s oeuvre, in portraiture and landscape, beyond the Civil War.

By now, Gardner’s stock has risen so high that, except in the popular mind, it almost surpasses Brady’s. Curators no longer slight his importance as an artist. Jeff Rosenheim’s recent blockbuster history of the Civil War went so far as to cite an 1865 Gardner photo of a crowd of bystanders at Lincoln’s funeral as the beginning of street photography. As Keith Davis writes in the preface here, it’s a just irony that this Scottish immigrant “ended up with the most profoundly ‘American’ career of any photographer of his generation. In the critical decade of the 1860s, his work took him closer than any of his peers to the nation’s cultural and historical heart. When we think of the key events and personalities of this era, we recall Gardner’s photographs more often than anyone else’s.”

Jane L. Aspinwall’s book should further enhance Gardner’s reputation. Her two years of research have produced many new details about his career, especially what he accomplished with two post-war projects that he undertook in 1867-68: Across the Continent of the Kansas Pacific Railroad (Route of the 35th Parallel) and Scenes in the Indian Country.

Gardner (1821-1882) emerges in Aspinwall’s telling as a complex and an attractive personality. His upbringing in the West Central Lowlands of Scotland, in a community organized according to Robert Owen’s Socialist principles, no doubt shaped his egalitarian beliefs, including his fervent abolitionism. His decision in the last 10 years of his life to found a life insurance company was above all, according to the Mason who delivered the eulogy at his funeral, based on a desire to improve the lives of the working class.

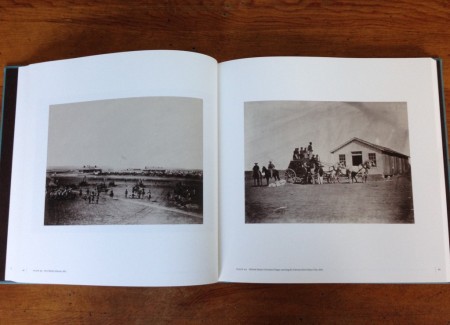

As a landscape photographer in the American West, Gardner was a pioneer. His work in 1867 for the Union Pacific Railroad, Eastern Division, as it was tracing a path across Kansas along the 35th parallel, coincided with O’Sullivan’s survey work for Clarence King’s survey along the 40th Parallel, and preceded William Henry Jackson’s for Frederick Hayden’s expedition in the Yellowstone Region, and John K. Hillers’ for John Wesley Powell’s along the Colorado River into the Grand Canyon.

All of these men were engaged in what Robert Sobieszek once called “conquest by camera.” Survey parties were assembled to help the East to map the West and to displace the local population of Indian tribes who claimed these lands as rightfully theirs, either as hunting grounds or settlements, and who were sporadically attacking the intruders. The railroad, the telegraph, and firearms, aided by photography, were tools asserting the U.S. government’s technological superiority and manifest destiny.

Gardner’s attitude toward his adopted country (and employer), and what they were doing to aggravate the fraught situation of the Plains Indians, is hard to guage. In 1867 he had been commissioned by a British speculator, William Henry Blackmore, to make formal portraits of tribal dignitaries who visited Washington, D.C. for treaty negotiations. (One of these, included here, is a magnificent 1867 group portrait of a Sauk and Fox delegation.) Across Kansas later that year he photographed U.S. troops or members of the survey party seated peacefully with Mojave Indians. His documentation included their churches and schools, such as St. Mary’s Mission because, as he wrote, “education lies at the root of national elevation.”

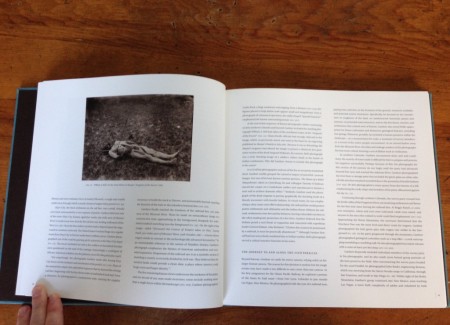

On the other hand, as Aspinwall notes, as a conclusion to the published album of railroad photographs, he included William Bell’s gruesome 1867 picture of a U.S. cavalry sergeant’s mutilated corpse, the chest cavity knifed open, the body pin cushioned with arrows. “In visual terms,” she believes, “he was emphasizing a clear cause-and-effect relationship: the railroad line would protect prairie settlements and ultimately end the Indian threat.”

Gardner needed to please both his employers and viewers back home. He couldn’t render the land so flat and featureless that possible settlers would be put off by a blank horizon; nor could he make the unknown country look barbarous and untamed. His solution, in several cases, was to highlight existing pieces of the railroad—engines, tracks, bridges, depots—in the frame. “While other government sponsored surveys reported difficult terrain and daunting construction challenges,” Aspinwall writes, “Gardner’s underscored the appeal—from an engineering standpoint—of the topography of the plains.” Extending more lines into the West was therefore no big deal for businessmen back East; it would simply require doing more of what already had been done, obviously visible in the photographs.

After he returned to Washington, D.C., Gardner was chosen in the spring of 1868 to document the official treaty negotiations taking place at Fort Laramie, Wyoming between the Northern Plains tribes and the federal government. General Sherman had indicated what was at stake, who held the upper hand, and the consequences of his partner across the table for failing to allow further railroad construction: “The Great Father wishes us to be kind and liberal to the Indians of the plains, if they keep peace; but if they will not hear reason, but go to war, then he commands that these roads be made safe by a war that will be different than any you have ever before had.”

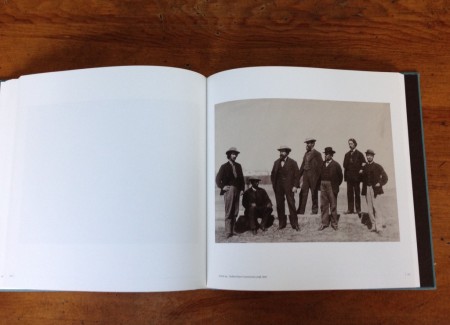

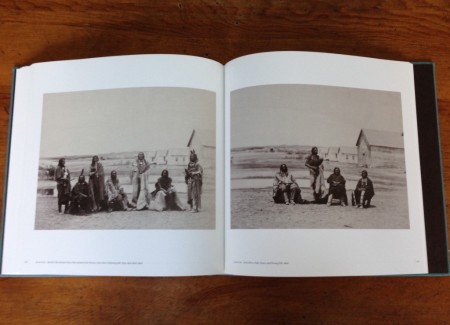

Gardner’s work from these talks was never tidily organized but Aspinwall discerns that he used his large-format camera for portraits of the male principals and a stereo-camera for scenes of daily life, often of women and children cooking and sewing. One must be careful not to exaggerate his talents as a photographer. His compositions weren’t as daring as O’Sullivan’s or Barnard’s, much less Muybridge’s or Watkins’. In his group portraits, he commonly did not more than arrange his subjects in a line and pressed the cable release.

His genuine curiosity about the Northern Plains way of life, however, is undeniable. The pictures are striking in their realism. None of them have the lustrous glow with which Edward Curtis surrounded his recreations. As Aspinwall writes, he “could be seen as the first and last to document a rapidly dwindling people accurately. Even as he was photographing, the traditional Indian way of life was being replaced by a government-imposed system.”

Whether anyone’s way of life can ever be uncontaminated by outside entities for long—and whether that is even desirable—is open to debate. Gardner must nonetheless have recognized he was being granted unprecedented access to a rare event, as he had been in 1865 at the execution of Lincoln’s assassins. He certainly took full advantage of the opportunity.

With reproductions in 300 line screen duotone, and Thomas Palmer separations, this gorgeous book—far superior in this respect than Katz’s—is an opportunity as well. Gardner now belongs in the pantheon of American photography and these unusual images illustrate some of the reasons why.

Collector’s POV: Single image prints by Alexander Gardner have only been intermittently available at auction over the past decade, with most finding buyers under $10000. Full 2 volume sets of his Photographic Sketch Book of War have fetched upwards of $85000, and a set of 4 photographs depicting the hanging of the Lincoln conspirators recently sold for $100000.