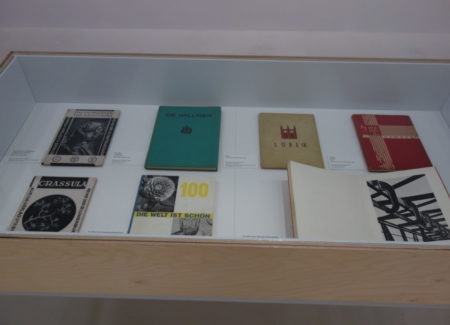

JTF (just the facts): A retrospective exhibition consisting of a total of 160 black and white photographs, variously framed and matted, and hung against white and light grey walls in a series of connected spaces. All of the works are gelatin silver prints, made between 1922 and 1966. The show also includes 1 vitrine displaying 7 photobooks. (Installation shots below.)

A catalog of the exhibition has been published by Éditions Xavier Barral/Fundación MAPFRE (here). Hardcover, 320 pages, with 190 black & white reproductions. Includes essays/texts (in French) by Sérgio Mah, Herbert Molderings, Stefan Gronert, and Kerstin Stremmel.

Comments/Context: The fact that this comprehensive Albert Renger-Patzsch retrospective, which originated at the Fundación MAPFRE in Madrid and is now on view at the Jeu de Paume in Paris, isn’t traveling to the United States is a major missed opportunity to educate Americans about the German’s linchpin place in the history of 20th century photography. For many here, Renger-Patzsch is largely an unknown, a secondary European maker of deadpan images that seem to be part of the between-the-wars Modernism that is so often held up as a pinnacle of the medium, but are somehow not quite the same as what Edward Weston was doing. And so his many artistic contributions get quietly undervalued, simply because not enough education and broad-based exposure has taken place.

To understand where Renger-Patzsch fits in the wider historical narrative, we have to go back to the period right after World War I. In much of Western Europe and America, the soft-focus painterliness of Pictorialism was still the reigning photographic aesthetic, soon to be washed under by the wholesale turn to the crisp “straight” precision of Modernism and its optimistic celebration of the newness of industry, technology, and urbanization. In Germany, the situation was similar but essentially slightly different – the stylized emotions of Expressionism were the dominant aesthetic there, with experimental approaches to the arts embraced as a deliberate rejection of the punishing realism of the recent war. So when Renger-Patzsch, August Sander, Karl Blossfeldt and others in Germany embraced a fresh kind of formal practicality with their Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement in photography, they too were reacting against the overreaches of heightened emotionalism, but their sobriety was still rooted in the traumatized soil of recent German history. Thus when we go back and try to reconcile Stieglitz, Weston, and the Group f.64 photographers with Renger-Patzsch and the Germans of the 1920s, even though there are plenty of broad brush commonalities, we start to see minute but ultimately important divergences of fundamental mindset that manifest themselves as nuances of photographic tone, texture, and warmth.

This retrospective is generally organized chronologically, and this step-by-step approach allows us to follow along as Renger-Patzsch incrementally develops his ideas. In his photographs from the early 1920s, we see him actively returning to first principles, taking up-close images of succulents and other plants with rigorous scientific detachment, allowing the mechanistic eye of the camera to strip away all vestiges of personal involvement. The pictures (which became the photobook Die Welt der Pflanze (The World of Plants) in 1924) are marvels of technical clarity, with fibers, thorns, leaves, and petals seen with dry neutrality, their inherent geometries and patterns coming forth with understated wonder. He then applied the same meticulously deliberate eye to the slow everyday life in the Halligen islands of northern Germany, his photographs of wading, boating, and working on the coasts and canals similarly emptied of romance and typical landscape grandeur. They are stepped back, gentle and quiet, their overlooked elemental forms (the sinuous S of the waterway, the geometric slats of a rickety footbridge, the textured lines of a coiled white rope) seemingly rediscovered by his patient attention.

These two projects are an essential prelude to Renger-Patzsch’s most well known body of work, Die Welt ist Schön (The World is Beautiful) from 1928. It was as if these earlier efforts crystallized the radical-for-the-times idea that strict photographic clarity had an inherent beauty all its own. Once Renger-Patzsch adopted this worldview, nearly any subject could be photographed with an eye for its unique structures and forms – both natural and man-made objects could be reduced to their component essentials, thereby unlocking their layers of neat organization. While Edward Weston and Imogen Cunningham (among others) were also following a similar line of aesthetic thinking at roughly the same time, Renger-Patzsch’s photographs are much cooler and even more arm’s length, with no patinas of warmth or appreciation. He jumps from floral specimens to blast furnace smokestacks, and back to the eye of snake, an array of silver shoe lasts, a pair of hands in prayer, and a bunch of electric insulators, finding formal clarity in each, without regard to some larger implication or emotional tenor. A baboon’s face, the frothy waves at the beach, the hands of a potter, a old cobblestones on the street, the buttresses of a church, a formation of ice – each is an opportunity to discover the entrancing underlying structure of clear-eyed reality.

In 1929, Renger-Patzsch moved to Essen in the Ruhr River valley, where the countryside was being actively transformed by industrialization. Until this exhibit, I had always found the landscapes he made in and around Essen in the 1930s to be rather dull, full of rolling hills interrupted by growing villages and factories. But whether it was the way they are presented in this exhibit or simply my own increasing understanding of how Renger-Patzsch was seeing the world, these landscapes now suddenly make much more sense – they are an unadorned and systematic view of two competing systems in conflict. Nearly every one is a meticulously constructed juxtaposition, mixing symbols of old rural life (framework houses, snowy fields, majestic trees, lampposts, clotheslines, wooden fences, even cows) with the encroaching presence of the new factories. Overly tall brick buildings stand out against the flatness of the land, belching smokestacks decorate skylines, and mining infrastructure, electrical wires, train tracks, and slag heaps mingle in the haze. Once this fundamental contrast becomes apparent, the images are like a theme and variation exercise, often with foreground and background set in elegant opposition. Renger-Patzsch is still seeing with the same deadpan precision, he’s just walked back to take in a much wider view of the changes going on around him, seeing larger patterns, paradoxes, and realities than those observable at close range.

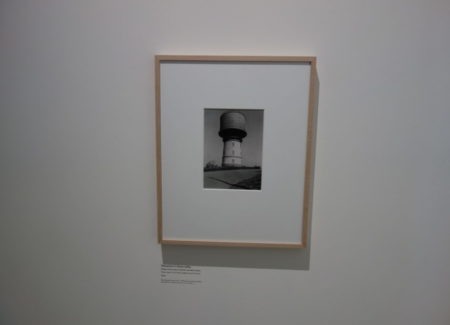

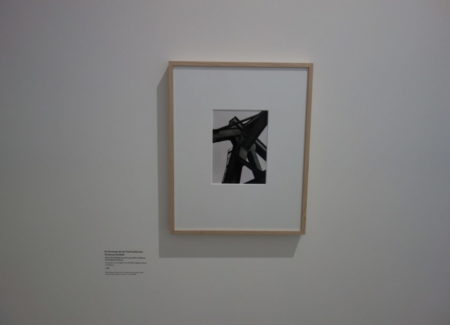

After World War II and into the early 1950s, Renger-Patzsch turned his attention more and more to the geometries of industrial architecture. While he had pointed his camera at the guts of locomotive wheels, milling machines, and various arrangements of pistons, cogs, and bobbins back in the mid 1920s, the 1950s pictures are more spatial, turning winding towers, head frames, coal bunkers, and pass throughs into blocks and diagonals against flat mid-grey skies. Many are investigations of dark and light, or of edges and angles, the buildings like reductive elemental forms connected together for varying purposes. Like the landscapes, they are intentionally systematic, and they undeniably set the stage for Bernd and Hilla Becher’s rigorous formal studies of German industrial architecture in the 1960s.

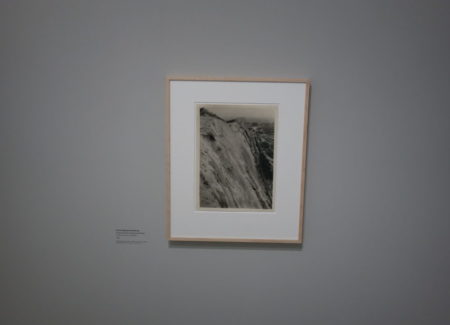

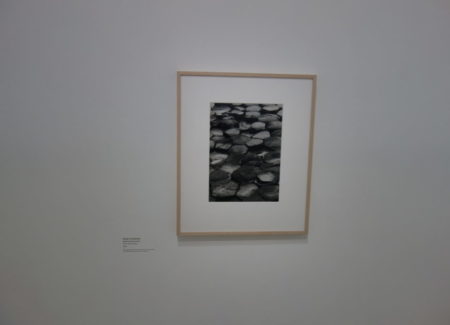

In his later years, Renger-Patzsch left the mechanisms of man behind and settled into deliberate studies of trees and rocks, and while the clarity of his eye is still fully evident, understated reverence and warmth make more of an appearance in the pictures than ever before. Many of his portraits of trees, their gnarled trunks twisted and weathered by time, reach a magnificence of execution not seen since Atget’s trees decades earlier. Single dark specimens stand out against the forest, bulbous trunks become studies of texture, and weeping leaves and spiky branches are reduced to comfortable natural rhythms. Many of his best images sit at middle distance, taking in the depth and density of the forest, where a dirt path stretches into the distance, snow heightens the contrast, or fog increases the fairy tale mystery. His rock studies are similarly attentive, seeing the fundamental realities of geology, from flat facets and undulating curves to busy conglomerates and rocks filled with trilobite fossils. When he visited quarries, he was of course drawn to the lines and geometries of cut stone, where the layers and linear patterns become more prominent. But many of his images of rocks from the early 1960s finally let go of those hard edges (just a bit), seeing and accepting the rounded corners and weathered indentations made by water.

What is remarkably absent from this thoroughly satisfying presentation is the impulse to tactile glorification that inhabits and enlivens so many Modernist images – there are almost no burnished surfaces, no shines, no romantic views of what the future brings on view here. Renger-Patzsch never seems to have gone down that path, never needed to amplify, instead seeing the world around him in the barest of terms, its inherent simplicity (and beauty) evident right before his camera and enough on its own. That consistent reserve and deliberate control is quietly powerful as seen in this exhibit. For many, his images might feel less grand or full than a sensually linear Weston nude or an energetic Bourke-White industrial from the same period, but don’t underestimate Renger-Patzsch’s contributions to the trajectory of Modernism. His distance has its own reasons and pleasures. Over some five decades, he never relinquished his trust in the power of photographic objectivity, instead embracing its strength as a pathway to seeing the order in a chaotic world.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum retrospective, there are of course no posted prices. Renger-Patsch’s prints are routinely available in the secondary markets, particularly in the European auctions. Recent prices have ranged between roughly $1000 and $180000.