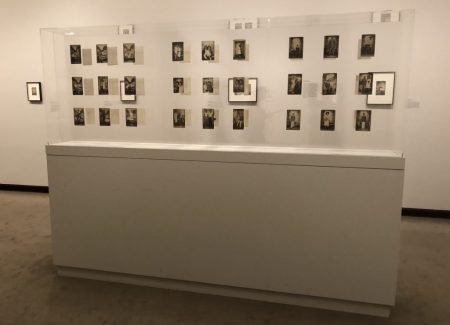

JTF (just the facts): A total of 187 vintage photographs displayed on walls and in vitrines in a small gallery on the museum’s second floor.

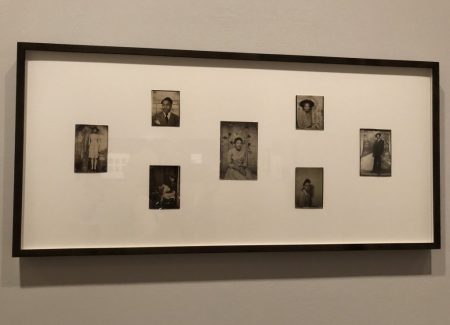

One of the photographs is a ca. 1855 daguerreotype, measuring 3 1/4 × 2 3/4 inches, in an antique cabinet card frame. A second photograph is an 1864 albumen silver print, measuring 3 3/8 × 2 1/8 inches, glued to a carte de visite mount. The remaining 185 photographs are gelatin silver prints from the 1940s and 1950s, each measuring between 2 ¼ x 3 ¼ inches and 5 x 7 inches. 144 of these prints are floated on Plexiglas panels within double-sided Plexiglas cases; 33 more are matted and framed singly or in pairs or groups and hung on the gallery’s white walls. A further 8 are displayed in a vitrine together with a vintage PDQ Camera and a facsimile of a 1942 advertisement for the same.

(Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: This thoroughly engaging and, at times, discomfiting exhibition opens with a pair of nineteenth-century photographs, both of famed black abolitionists. The first is a daguerreotype portrait of Frederick Douglass, who believed that as a tool for positive self-representation, photography had a role in ending slavery and a continued purpose in countering racism. It is accompanied by a quote taken from Douglass’s 1861/65 lecture “Pictures and Progress”: “The process by which man is able to possess his own subjective nature outside of himself—giving it form, color, space, and all the attributes of distinct personalities so that it becomes the subject of distinct observation and contemplation—is at bottom of all effort and the germinating principle of all reform and all progress.” Nearby, a carte de visite featuring a photograph of Sojourner Truth, who copyrighted her own image and sold cards like this one to finance her 1864 speaking tour, reads simply: “I sell the shadow to support the substance.”

With these two quotes, the Met acknowledges both the power and the limitations—the former celebrated by Douglass; the latter astutely identified by Truth—of self-fashioned images such as the ones in this show, which was organized by the museum’s photography curator Jeff Rosenheim. The exhibition consists of nearly 200 studio portraits of working- and middle-class African Americans taken in the 1940s and 1950s. That they should be on view at a major New York museum reflects a growing interest among scholars and academics in vernacular photographs, which, beyond offering glimpses into the lives of their subjects, may, as well, contain clues to larger societal structures and forces. Although long cherished by collectors—original prints made by the great Arkansas portraitist Mike Disfarmer, for example, bring high prices on the art market—and an influence on photographers from Walker Evans to Deana Lawson, material from such sources as family albums and police archives was rarely seen in museums until the 1990s, a moment coinciding postmodern distrust of the so-called documentary image.

Following on several recent and rather more wide-ranging exhibitions of vernacular photographs of African Americans—most notably “Everyday Beauty” at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., which closed this past February—“African American Portraits” is limited to the output of small, presumably black-owned portrait studios operating in the American South and Midwest between 1940 and 1960. The Met, which by its own admission has few portraits of African Americans in its collection, recently acquired some 250 of these pictures from a single owner. This narrowing of focus to a very particular type of photograph, while important in terms of scholarship, also—more disturbingly—underscores the objects’ status as collectibles.

A majority of the photos on view are floated within tall Plexiglas cases, so viewers can see both their fronts and their backs. In most instances, however, the only writing on them is the museum’s own acquisition number. The subjects of these photographs, with few exceptions, are anonymous, and the names of all but two of the photo studios—though certain identifiable backdrops recur throughout the show—have been lost to time.

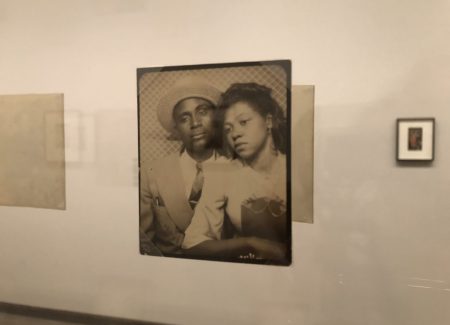

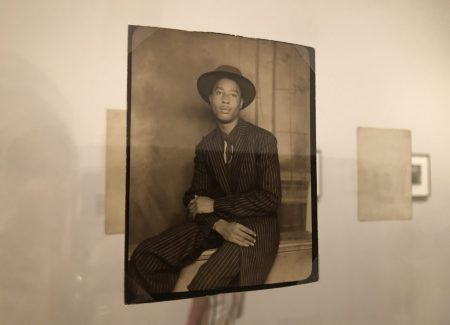

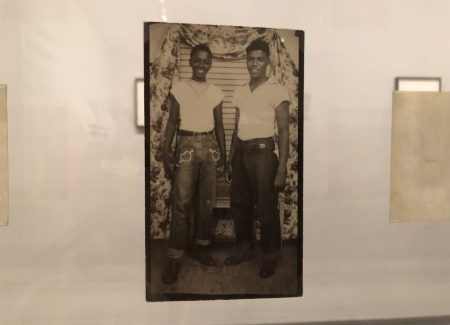

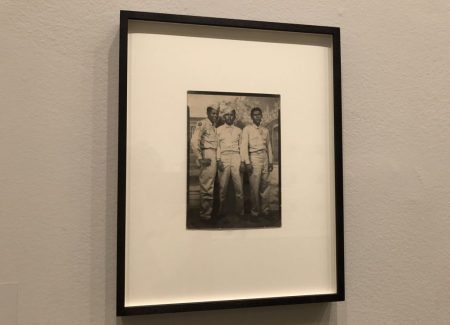

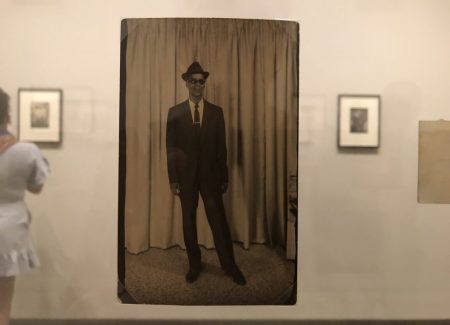

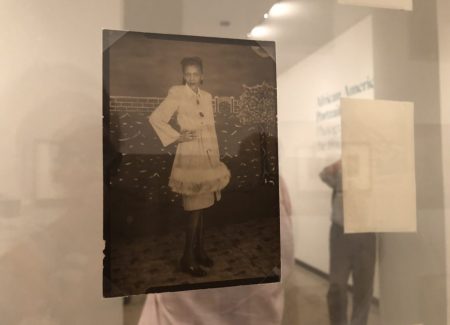

The images of these unidentified men and women, however, are nothing short of riveting. Every picture was taken with a bulky PDQ camera (Photography Done Quickly), which used direct positive paper rather than negative film and could make black-and-white prints in only a few minutes. These could be hand-tinted for an extra charge, and many of the pictures here glow with applied color. The album-size prints show loving families, proud mothers with their children, siblings, best friends, and amorous couples, commemorating their connection to each other or to the person for whom the picture was taken. Most are dressed in their Sunday best—shiny bags and soft hats, stockings and natty suits abound. A fair number of young men and women are in uniform, on their way to serve in segregated units, leaving behind their images for others to keep safe.

The painted scenes that form many of the backgrounds range from near folk art to realistic, dimensional constructions and variously depict elegant conservatories, sedate parlors, formal gardens, and pastoral landscapes. These idealized surrounds convey optimism and hope, though in the world outside the studio, Jim Crow still reigned in the South, World War II was still being fought, the Great Migration was still carrying successive waves of African Americans northward, and the civil-rights movement was underway. While little is known of the circumstances of the people in the pictures, the uncertainty and promise of the times can be felt in their determination to mark the moment. An inscription on the back of a photograph of a young man with a beautiful young woman on his knee begins, “I love a girl . . .” Another one, of a dashing swell in sunglasses, hat, and knife-creased pants, reads, “Beverly Baker, twenty years old.” A man who has dressed up his khakis with a plaid jacket and a felt hat, and a matron in a bright pink fascinator are no less vividly present.

The immediacy of these images is the great strength of the show, but also, finally, the source of yet another kind of unease. Seen reflected in, and through, the Plexiglas cases, I and my fellow visitors to the exhibition, all similarly enraptured by these tiny vignettes, seemed less substantial than the people in the pictures and more like ghosts.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum show, there are of course no posted prices, and given that most of the makers are unknown/anonymous, we will forgo our usual discussion of secondary market prices.