With so much innovation going on at this particular moment in contemporary photography, it might seem delusionally foolhardy to think we might be able to make critical sense of it as it is happening. But in the last year, I felt a real frame-breaking shift in the fabric of the medium, so much so that I have now begun to see the past few years as the precursors to a broader new imperative that is beginning to reach maturity – the rise of what we might call interdisciplinary photography. This approach has developed so much momentum that it is literally engulfing the leading edge of the medium, gorging itself on adjacent artistic methods and incorporating them piece by piece into a larger whole. It’s a voracious beast that we have unleashed, and it’s currently expanding in nearly all directions at a breakneck pace.

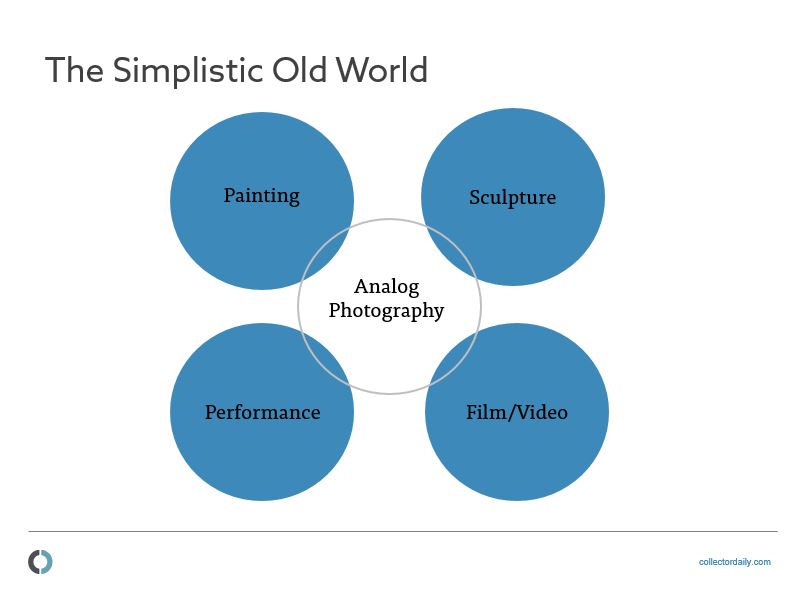

To understand how we got to this place, I think we have to go back to the beginning of the digital revolution. In the slide below (which I developed for a recent lecture), I have tried to graphically depict the simplistic old world, where analog photography was basically a separate entity, next to and often minimally overlapping with other artistic traditions. In this age, when photography mixed with other media, it was almost always to document those other activities, and there was minimal connection between the circles. The Pictures Generation artists and those that followed in their appropriating footsteps began to tear down the walls that had kept photography so isolated, and with the rise of the Dusseldorf school and large scale printing, we started to see attempts to make photography more relevant to the contemporary art dialogue. But on the eve of the digital transformation, I think photography still entered this discussion on its own terms and rooted in its own traditions; it was following and responding rather than leading.

With the benefit of hindsight, I’d like to make the argument that much of the first 15 years of the digital photography age, say from roughly 1995 to 2010, we were in a period of direct technical substitution, where a new technology gradually and eventually almost entirely supplanted an old technology. During this time, early adopters had to deal with constantly evolving software tools and had to improvise and experiment to recreate effects that were commonplace in the previous methodology. Along the way, we saw the beginnings of new digital/Internet-based experimentation, where uncharted white space suddenly opened up for those artists willing to go beyond their existing preconceived boundaries and aesthetic limits. Looking back at those first digitally stitched and composited works, those that first took advantage of mirroring or color tweaking, or still others that first scavenged images from the net, there is a kind of nostalgia – those artworks are reminiscent of a particular, now bygone time, “so 2006” we might say, without seeming flip.

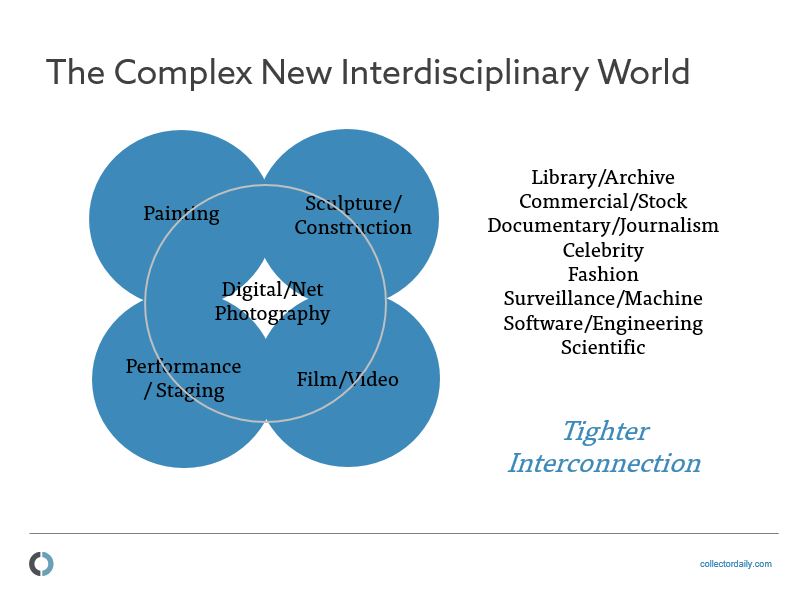

But along the way, an unexpected, or at least somewhat unforeseen, confluence took place – the larger wave of digitization sweeping through our lives (the one that disrupted music, books, and shopping, and so many other daily activities) began to intermingle with the now digital nature of photography. And so digital/net photography began to spill over into video, and painting, and sculpture, and performance art, with very little to halt its onslaught. To make matters worse (or better, depending on your point of view) previously completely unrelated image stockpiles, from archives and libraries to surveillance footage and scientific imaging (now digitized) all converged at one single point. Suddenly, there was an ocean of available raw material (exponentially augmented by the advent of the cameraphone), all of which was usable on a common platform. (The slide below attempts to show this expanding presence of digital photography and the nearby genres on which it is increasingly feasting.)

When I look back at the past few years, especially at the photographic work shown in New York’s rawest and most emerging galleries, it is now clear that the expanding footprint of digital photography had increased to the point where it was becoming interdisciplinary. Part of this intermixing was enabled by the pervasive adoption of the inkjet printer and its ability to print a photographic image on nearly any surface. But the larger effect is I think a result of a more subtle shift in artistic mindset, from “I am a photographer using a camera to document X” to “I am an artist who is using a computer/scanner/camera to mine an archive of found imagery, using those images to build studio installations and sculptures, which I then rephotograph multiple times and reprocess with a software algorithm” or some such equally complicated combination of steps, processes, and intermingled, mashed up ideas. This is not to in any way imply that the traditional mode of photography has somehow been supplanted or become less relevant; on the contrary, I think there will always be a place for superlative straight photography. But out on the bleeding edge, it seems like there are less and less straight shooters and more and more interdisciplinary mixers.

Photography like the kind I am describing has become intricately layered, with numerous connections and tangents to be traced and followed, the final output of which may be a photograph or may be something else entirely. Since we are in the early days of the maturation process of this approach, we are still seeing our share of convoluted Frankensteins, but what should make us excited is that so much new territory for experimentation has now opened up. I think we will look back on these years as a time of incredible flowering, with the first wave of the digital revolution already passed and washed out on the artistic beach and the second wave beginning to crest with power and majesty. For those fools and idiots peddling their “end of photography” doomsday scenarios, it’s clear that they just aren’t paying attention to the single most exciting burst of creativity the medium has seen in decades.

Part of what is fascinating about this particular moment in the evolution of interdisciplinary photography is that we haven’t yet evolved a sophisticated vocabulary for talking about it. Both the contemporary art galleries (who are less versed in the history of photography) and the specialist photography galleries (who are less versed in the micro trends of sculpture, painting and other media) are both scrambling to find ways to explain this work to collectors; what’s happening is more than appropriation, and surface, and reuse, and manipulation. Both sets of galleries are coming at the work from skew angles (given that these works are inherently hybrids), and both will need to learn from the other side if they are to capture the complex resonances that this interdisciplinary photography offers. This will be even harder for the specialist photography galleries who are deeply rooted in vintage photography; I see these venues struggling to stay relevant in these new discussions unless they can boldly pivot into the fray and turn their knowledge and context into an advantage. And many established venues in both camps simply haven’t engaged with this new style of work yet, leaving the door open for emerging galleries to carve out and defend the territory.

When I step back and look at my gallery log from the past year, it’s truly astonishing to see how much of the photographic work I found original and exciting falls under this interdisciplinary umbrella; it’s not that straight photography can’t still be astonishing, it’s simply that there is so much crackling going on when photography is thrown into the blender with half a dozen other artistic modes. Let’s take as just one example the mashup of photography and sculpture, and the inherent exploration of object quality, physical presence, and texture that such a combination implies. Letha Wilson (here and here) has mixed grand photographic landscapes with poured concrete and two by fours to create works that interleave the natural and man-made. Diana Cooper (here) and Jennifer Williams (here) have used photographic imagery as part of larger wall covering collaged installations that transform space. Brendan Fowler (here) and Carey Denniston (here) have interrupted our view with smashed frames and obscuring panels. Sara VanDerBeek (here) has printed on mirrored sheets, while Ethan Greenbaum (here) has printed on molded transparent plastic. Elad Lassry (here) and Sissi Farassat (here) have decorated their works with silk pleats and shiny sequins. And what about those artists who are working with staged studio constructions that are truly sculptural like Yamini Nayar (here), Shannon Ebner (here), or David Gilbert (here)? In just this one tiny vein of exploration, there is an overwhelming amount of innovation. If you’re game, John Houck, (here), Lucas Blalock (here), Michele Abeles (here), Annette Kelm (here), Travess Smalley (here), Trevor Paglen (here), Owen Kydd (here), Mariah Robertson (here), and Penelope Umbrico (here) might take you down any number of other unexpected interdisciplinary roads, and this is just a sample of the artists who had a solo show in New York in 2013 that we reviewed – if we open it up further, the list of innovators get even longer. Intellectually, my favorite interdisciplinary idea of the year was Garrett Pruter’s paintings made from melted down photographic emulsion (here); they seem to embody this cross-functional experimental enthusiasm that is sweeping through the ranks of emerging photographer/artists. Is any of this photography in the traditional sense? No. Is any of it exciting and thought provoking? Damn right it is, even if Edward Weston might not approve.

So the important story of photography in 2013 was really about blurred lines (with a grudging nod to Robin Thicke’s Marvin Gaye ripoff). The maturation of interdisciplinary photography has far reaching implications for everything from how we talk about and define the medium to how artists execute their craft. But more thrillingly, we have now assembled the pieces necessary for explosive, disruptive change in photography; it’s a recipe for something to “go right” and I expect we will see more signs of radical interdisciplinary innovation in 2014.

I think photography has traditionally differed greatly as a medium from the other art forms due (at least in part) to the almost fussy degree of formalism associated with it. ‘no, not silver gelatin, it must be a platinum print’, ‘color, no real photographer would print in color’, etc., etc., etc. and much worse.

In my view, which could be way off, photography itself killed paintings formalism. There was no need for technical mastery when, by the mid-1850’s, anyone with a camera could produce a better reproduction of a sitter than any painter. There was no need for the formality of portraiture, the restrictions, etc. So then you turn to subject matter, now that the technical is minimized. Well, the impressionists did their number there, busting things wide open.

All-in-all, abstract painting could only arise, IMO, in a world where formal painting for reproduction’s sake was no longer a necessity and subject-matter taboos were broken. Those two, combined, forced evolution.

I have always thought photography will evolve as an ‘art’ when we no longer need it for technical mastery. I think (as you appear to) that we are currently right there or have just passed that point in the recent past. Technical innovation, the digital camera, photoshop, etc. has put us into a world where a teenager can reasonably make pictures of basically the same quality as any master. So, if technique is now moot, and subject matter taboos have already long since been destroyed, we should be at the dawn of post-photographic abstraction.

And, i anticipate we will see many forms. Minimalist, conceptual, etc., etc., etc. Right now I see 3 trajectories forming: those who are taking the digital and running with it (e.g., Vierkant, Smalley, etc.), those who are reacting against the digital and moving towards more physical work (e.g., Mariah Robertson, Sam Falls, Fowler, etc.), and those who are straddling the line between these (e.g., Matthew Brandt). I think history will look back on this period of time quite favorably. Should be fun to watch.

I guess my question is how is this all different from the Pictures Generation and conceptual wok done in the 70’s? Oh, you use Photoshop to do it instead on by analog means? Or is it because it can be disseminated more easily with the internet or you have more choices of image repositories to choose from because of the internet? Ok, but to me it still seems like a lot of rehashing of Prince, Mandell and Sultan, Heineken, Divola etc.

I’ll let another old man rant about process for process’s sake.

http://www.paulgrahamarchive.com/writings_by.html

This notion of ‘interdisciplinary photography’ is interesting, but the concept is not entirely new. The 1980’s witnessed wonderfully innovative, exciting and fresh artworks – installations, projections, moving image (video primarily) – combined with photography in various guises. What’s exciting and wonderful now, is that there is such an expanded plethora of tools/materials for artists to easily access and utilize in their methodologies of production and creative expression; as well as a crazy ease at which to disseminate it. There are exceptional artists working … and there are exceptional gallerists/dealers that recognize and understand the work (some of us do have photo history, critical theory and art history backgrounds and experience in public art/media arts … sssshhhh).

There’s nothing particularly ‘traditional’ about photography—since its inception it’s been in a constant state of flux and always will be. That’s what, partly, makes it such an exciting and innovative form of visual art. Perhaps specific forms of photography become ‘traditional’ as a result of time passed.

Anyhow, wonderfully written piece. Thanks!

DLK’s enthusiasm for interdisciplinary photography practice has been clear for some time but as we also know the site totally values and promotes straight photographs, too this is nothing to get het up about. And as Paul Graham notes in the article referred to by Joe, (in Graham’s case when considering straight against constructed images) ‘it is emphatically not an either/or situation’. The same advice should apply here too, I think.

The work, artists and processes that this essay uses to illustrate this “new wave” of interdisciplinary photographic practice are diverse and I think, overall, a fair representation of what people are interested in aesthetically and conceptually in contemporary photography these days. This being said, I can’t help myself in being critical of certain visual trends that are pervasive and somewhat questionable within this new artistic program, this “next step” in the medium of photography.

I read an interview a while back (can’t find the exact quote or interview now, something on Vice’s site…) but another photographer was griping that “everyone wants to make work that looks like Roe Ethridge these days” or something along those lines. This sentiment, mixed with an infatuation with floral print, haphazard photoshopping, mirrors, florescent color palettes and the fetishization of inkjet printing on somewhat arbitrary materials makes a lot of this work fall flat for me personally. There’s a bizarre (and naive) attitude that the internet has somehow transformed artistic practice across the board and for the better that pushes me away.

I also didn’t see any mention of two artists that I believe embody this new way of approaching photography in a very thoughtful and effective way – those two being Taiyo Onorato & Nico Krebs. I can only hope that this movement or whatever you want to call it matures over the next decade or so and has the common sense and introspection to abandon the gimmicky trappings of “hipster chic”.

Many of the above-mentioned artists are operating in a thoughtful and provocative way and I don’t intend to bash their work or conceptual program. I believe that the issue lies in a broader program of imitation, techno-fetishism and thoughtless visual “pizazz” that galleries and museums seem to be going absolutely berserk for these days. Being a straight photographer using a camera as a tool is perceived as antiquated, whereas being and artist who USES photography to “explore ideas” while making screengrabs into 5′ wide C-prints is the height of sophistication.

The issue of not being able to discuss a lot of this new work within a broader framework might not have to do with a lack of vocabulary. Like a lot of fashion photography, I think that the awkward, weird never-been-done-before factor can only go so far. It will be very interesting to see where we’re at in a couple of years. Will this neon-web-based-algorhythmic-anything-goes-mashup bubble burst or will it just keep inflating and thinning out?

Amen to Jim’s comment.

@Pete – I don’t think it’s either or either, but as the title of DLK’s post above attests, straight has been temporarily but significantly pushed to the sidelines in recent years.