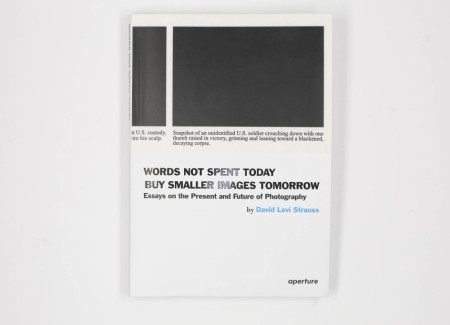

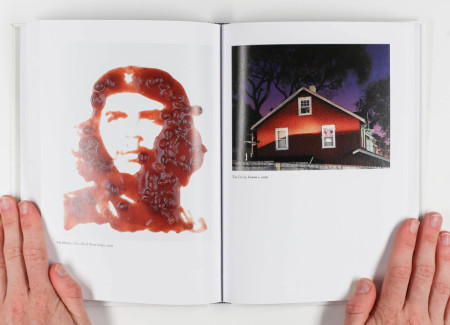

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2014 by Aperture (here). Flexibind, sized 6 x 8 1/2 inches, 192 pages, with 35 color and black-and-white images. $29.95. (Spread shots below, courtesy of Aperture.)

Comments/Context: David Levi Strauss is an academic who doesn’t write like one. A teacher of art criticism in the graduate programs at Bard and SVA, he has a second career as a poet. The dual pursuits criss-cross to the benefit of each. Even when discussing issues that come up in every postmodern classroom, such as the “aestheticization of suffering” or the “politics of representation,” he has sufficient respect for language that theoretical jargon isn’t allowed to clog his sentences.

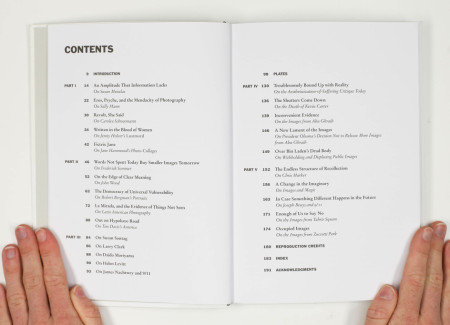

The slender essays (some less than 1,000 words but assiduously footnoted) in this book, his third with Aperture, corral a bawky herd of individual photographers: Susan Meiselas, Sally Mann, Carolee Schneemann, Jane Hammond, Frederick Sommer, John Wood, Robert Bergman, Tim Davis, Larry Clark, Daido Moriyama, Helen Levitt, James Nachtwey, Kevin Carter, and Chris Marker.

The latter half of the book is devoted to photojournalism and TV news imagery. Uniting everything are his thoughts on the ways that images, words, and audiences interact.

One of the strengths of Levi Strauss as a critic has been his unpredictable enthusiasms. As the roll call above indicates, he doesn’t favor one style or school—not today’s or yesterday’s major-league art stars, nor the austere Conceptualists favored by October magazine and Artforum, nor MoMA-stamped-and-approved documentarians.

If there’s any pattern to his taste, it’s a preference for artists such as Wood or Sommer or Marker who are similarly hard to pin down. Trained at the Visual Studies Workshop under Nathan Lyons, Levi Strauss learned to study the margins of American culture as well as photographs and to speak up for democracy and experiment wherever it can be found.

As a photography critic, he hasn’t been around the game as long as Lyons, John Berger, A.D. Coleman, Max Kozloff, Ben Lifson, Vicki Goldberg, Tod Papageorge, or Andy Grundberg. But like them, he is worth attending to because he has seen so much, known a lot of the key players, and listened to—or participated in—many old debates that are constantly revived as if they were new.

He was a college sophomore in Vermont when Susan Meiselas published Carnival Strippers in 1976. His appreciation of her strategy in that first book (how the reaction of the male crowd to the naked women was integral to the photographic drama) prompts the first essay, on her subsequent career. Recounting the grief she got from some artists and critics for her book on Nicaragua in 1991, he quotes Martha Rosler who at the time sneered that “documentary testifies, finally, to the bravery or (dare we name it?) the manipulativeness and savvy of the photographer, who entered a situation of physical danger, social restrictedness, human decay, or combinations of these and saved us the trouble. Or who, like the astronauts, entertained us by showing us the places we never hope to go.”

Whereas he may have once shared the qualms of Rosler and other denouncers of war or poverty photography, he seems to have reversed himself and now sides with Meiselas, one of the most thoughtful photojournalists around, and someone who has spent many years “trying to increase her understanding of the reception of images and their effects.”

In his shorter essay on Kevin Carter—the South African photojournalist who won a Pulitzer Prize for his 1993 image of a vulture lurking beside a starving infant in the Sudan, and who the next year committed suicide—Levi Strauss reverses himself again. After the upsetting picture became front page news around the world, Carter was viciously attacked by some for pressing the shutter instead of rescuing the child.

“This was too much reality for some viewers to bear,” writes Levi Strauss. “So they reacted in the normal human way: they blamed someone else. We want witnesses, but we demand sacrifice. Someone had to pay for this impropriety. Kevin Carter paid. He killed himself, at age thirty-three, on July 27, 1994, only two months after Mandela was sworn in as president of the new South Africa that Carter had spent his whole life imagining.”

This is a bit much. To blame anyone for another’s suicide is a dangerous charge to make. Carter had earlier made a good living by photographing unspeakable acts of mayhem in South Africa as part of the “Bang Bang Club.” Many in his profession have witnessed far worse (at Antietam, Auschwitz, the Vietnam War, the Middle East) and not taken their own lives. One of Levi Strauss’s heroes in this book, James Nachtwey, took a picture in Africa that is as ethically troublesome—of a skeletal man, near death and on his knees, reaching up toward the camera—and Nachtwey sleeps at night. No one has demanded that he be pilloried either. Interviewed on “Oprah,” subject of an Academy Award-nominated documentary film, he may be the most revered photojournalist alive.

By citing Levi Strauss’s vacillating responses to the perennial question of the photographer’s responsibilities, I’m not accusing him of anything except ambivalence, a feeling shared by all of us when looking at images of violence.

Photographers who haven’t been canonized by American museums (Moriyama, Bergman) inspire more original analysis from him than those who have (Levitt, Mann.) Jane Hammond proves to be a worthy recipient of his praise. He identifies precisely what makes her (or any) photo-collages successful: “She appreciates the information in photographs, for itself, for the reality it reveals, while also being dizzyingly attracted to its contingency. So that when she manipulates and recombines parts of images, she does so in a way that is consistent with the preexisting form-language of the photographs, and the resultant images, no matter how outlandish, remain insistently photographic, and therefore believable.”

His review of Tim Davis’s America, a book crowded with landscapes scarred by strip malls and office parks, inspires an outburst of rhapsodic Kerouac-ian prose. “These nocturnal images probe the commercial unconscious of America, the real estate of the realm, where those too poor to insulate themselves from consumer advertising live in its unrelenting glare.”

He gallantly defends Susan Sontag from his fellow students at the Visual Studies Workshop who, he believes, did not like her for invading their turf. This misplaces the blame, to my mind. It was fine that she brought her formidable intellect to bear on photography. It was also grossly arrogant of her to pretend she was the first to treat it with rigor and dignity while attempting to unravel its temporal paradoxes. The generalizations in On Photography were often sweeping and wrong, without historical foundation or footnotes; and her individual targets (Arbus, for one) were wide of the mark.

What upset his fellow VSW students and others in the “photography community” at the time was that so many in the broader intellectual community came to believe that Sontag had invented photography criticism. She herself was only too willing to propagate that fantasy.

That was Sontag: whether writing about film or painting, literature or politics, she needed to portray herself as a lonely discoverer, without peers or predecessors, except for a handful of illustrious, mostly dead, Europeans. (A.D. Coleman wrote a nasty review of the book and the phenomenon of Sontag that is worth looking up.)

The weakest part of the book is the last, in which Levi Strauss expresses his utopian liberal hopes for change after seeing the demonstrations in 2011 by masses of young Egyptians in Tahrir Square and by the Occupy Wall St. protestors at Zuccotti Park.

“As we watched the Egyptians recognize each other in January and February, and risk their lives to come together to demand freedom and justice, we Americans were reminded of where we came from, what we’ve been, and what we used to stand for, before the ‘Reagan Revolution’ and 9/11, before we fell into fear and bitter division. The Egyptians reminded us who we were.”

The critical acuity he brings to the analysis of photography elsewhere in this book deserts him as he lets nostalgia for the ‘60s and ‘70s soften his thinking. Surely, he might have suspected that images of crowds on a TV screen, in a region of the world that he had only a sketchy knowledge of, weren’t telling the whole back story. Knowing that the Egyptian military controls as much as 40% of the economy was a more reliable predictor of the future and should have tempered his euphoria.

What makes Levi Strauss worth reading even you won’t agree with him—and on every page I found myself quibbling with or objecting strongly to his assumptions—is that he writes and argues with eloquent passion.

The title of the book refers to a Sommer poem that reads in part:

“When the world was young images were strong

Images have sources and antecedents

to turn away from them is to have no images

to breathe life into

We have again become so young

that someone will have to turn on a light and find us”

Levi Strauss reads Sommer’s poem as an admonishment: “We have to spend more words to stimulate more and better images, and to resist control through images. If we don’t do it now, it will cost a lot more to do it later.”

The ease of the Google search and the staggering volume of images exchanged every day on social media make the task of the viewer even more urgent: “We take more pictures, but we look at them less often, and with less care. Consequently, our ability to decode images is actually decreasing. When words and images are reduced to ‘information,’ they lose significance and become elements that simply need to be managed.”

Blessings upon Aperture by keeping alive the quaint ritual of collecting criticism in book form. Just as photographs shouldn’t all be debased as information, Levi Strauss’s ardent words deserve a chance to become something other than “text.”

great comments for Levi