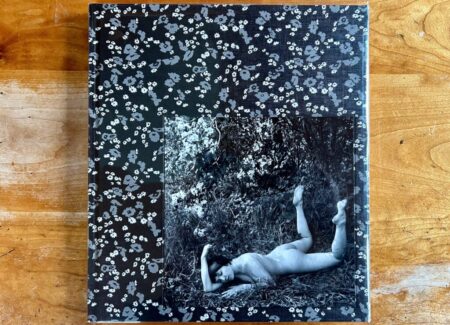

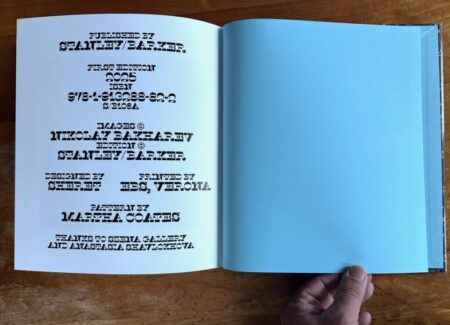

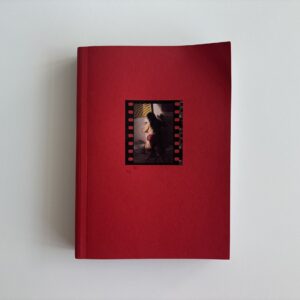

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by Stanley/Barker (here). Hardback with tipped in cover photograph (two versions available), 24×27 cm, 120 pages, with 50 monochrome photographs. Design by Sheret. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: When we last wrote about Nikolay Bakharev in 2015, the Russian photographer was exhibiting vintage silver gelatin prints at Julie Saul Gallery. Following the curatorial lead of his monographs People Of Town N and Amateurs and Lovers, as well as his Venice Biennale appearance in 2013, that show combined two related bodies of work under one catch-all title: “The People of Town N” (named for Novokuznetsk, Bakharev’s home city in Siberia).

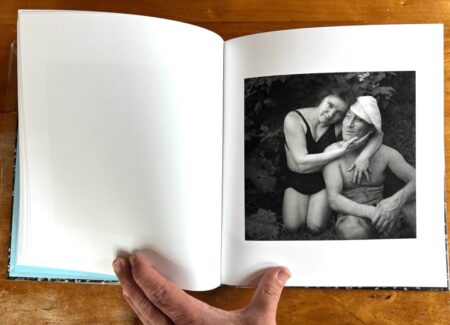

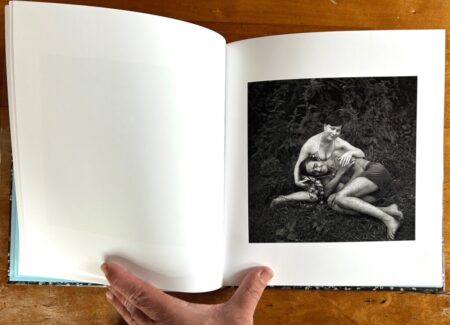

Although they were thrown together under one roof, each of Bakharev’s projects had a distinct visual style and working method. His Relationship series featured penetrating portraits of public swimmers in warm outdoor settings. He later followed up with some of these subjects to create his Interior and Study series, photographing people—mostly women— inside their own homes under bold flash, often in nude and provocative poses.

Reactions to the Julie Saul show were mixed. “The indoor shots aren’t as compelling, mainly because they have a clear erotic agenda,” sniffed Karen Rosenberg, writing for the New York Times. Collector Daily’s assessment (reviewed here) was more diplomatic. “The images are filled with subversive risk taking on both sides,” Loring Knoblauch wrote, “and the visual bargains and transactions Bakharev has made with his neighbors have led to some consistently sensitive moments of intimacy and warmth.”

In the 10 years since “The People of Town N”, the natural divide in Bakharev’s work has been further cemented, thanks primarily to Stanley/Barker. In 2016 the London publisher singled out his Interior and Study series for a photobook called Novokuznetsk. Cordoned into their own volume, away from the hagiographic glow of open air leisure, the interior studies assumed a transgressive and irrepressible edge. “Beyond the naked bodies,” wrote Aaron Schuman in an accompanying pamphlet, “[Bakharev’s] photographs are wondrously crammed, cluttered and overflowing with many more intriguing details than what initially appears to be the primary focus of his attention.” Bodies and clutter proved to be an attractive combination. Novokuznetsk is now out of print and difficult to find.

For their second Bakharev monograph, Stanley/Barker has turned the spotlight on his Relationship series. Cheryomushki follows the same dimensions and design as its predecessor, with similar patterned cover and tipped in cover photo. The interior pictures are roughly the same size as in Novokuznetsk, but their fidelity and resolution is improved (Novokuznetsk was one of the first books from fledgling Stanley/Barker and suffered from poor scans). The entire text is in English this time, targeting Bakharev squarely toward a Western audience.

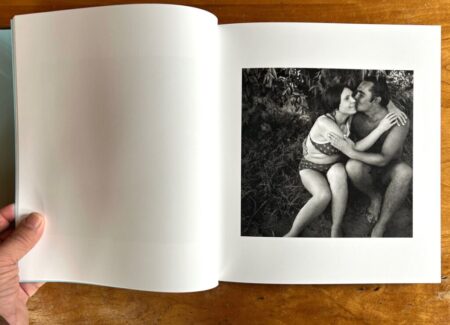

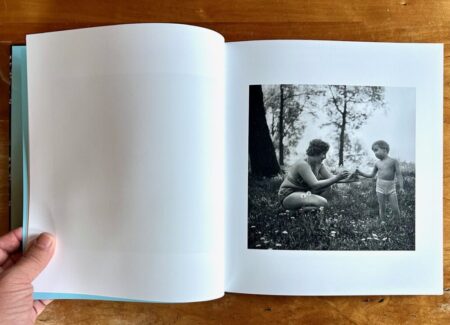

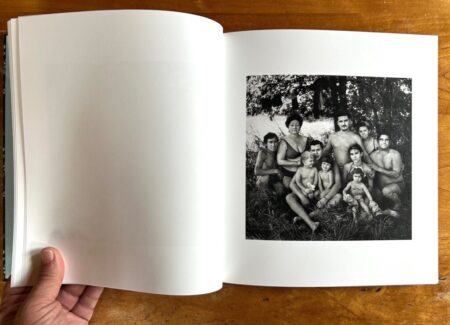

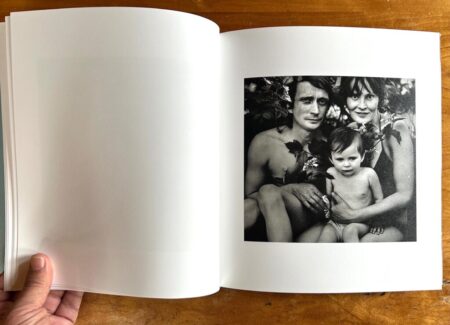

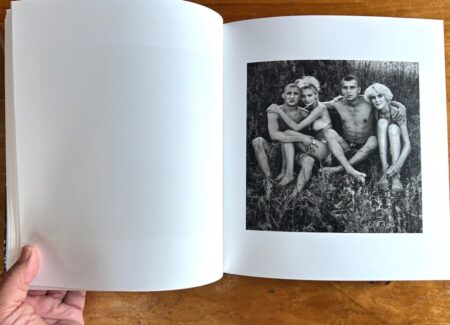

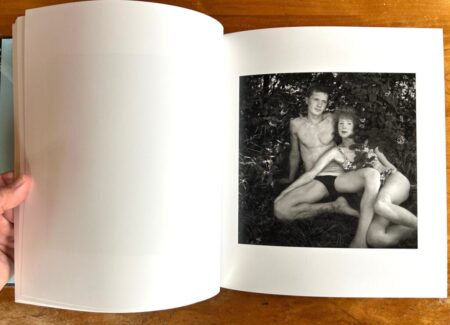

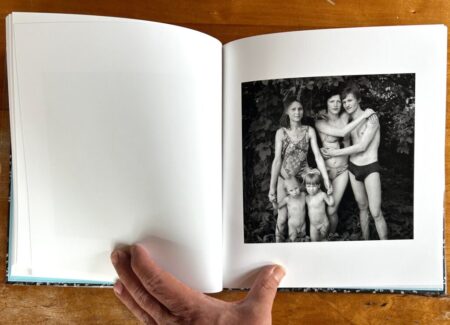

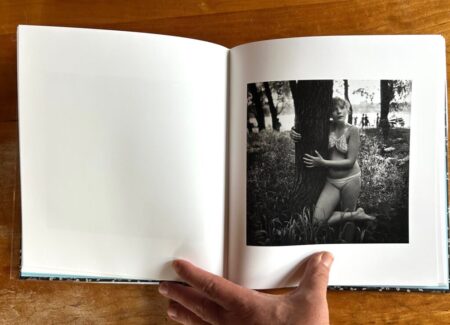

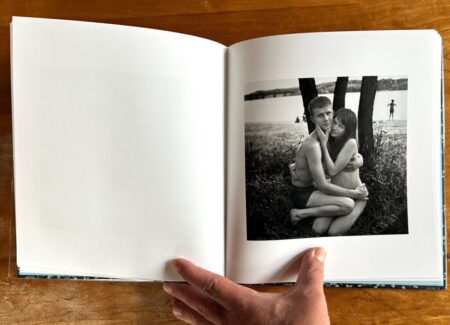

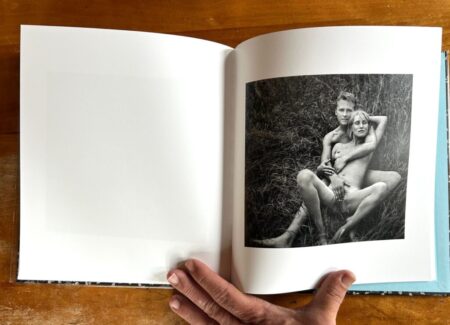

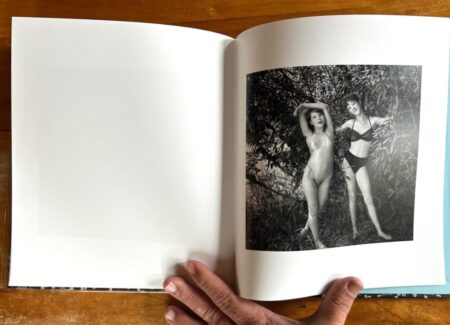

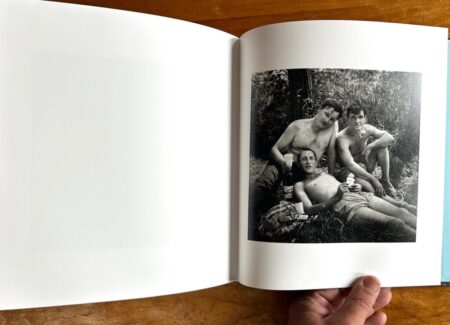

Cheryomushki takes its name from the riverside beach where its photographs were made in the shadow of a hydroelectric station in Novokuznetsk, in the 1980s and 1990s as the Soviet state was crumbling. The region was heavily industrialized, but you’d never guess it from Bakharev’s pictures. The settings are edenic and blissful. Swimmers relax and embrace in the woods, skin exposed, limbs unfurled, seemingly at total peace with their surroundings. For the moment at least, factories, criminal codes, and commissariat have faded from attention.

A brief introduction sketches a bare bones bio of Bakharev. He was born in Siberia (1946 in the village of Mikhailovka), orphaned at four, and placed in state care, where he discovered photography. As an adult he was assigned to work in a steel factory in Novokuznetsk. He eventually transitioned into photo assignments, shooting official portraits at first, and later private commissions. “As the USSR began to unravel in the 1980s,” sums up the intro, “he captured humanistic portraits…revealing a side of Soviet life rarely seen.”

One obvious reason such photos were rarely seen—at least publicly—is that the Soviet state prohibited nude photography. The empire wore no clothes, but for its subjects it was a different story. “Almost any image of a naked body was considered pornography,” says Bakharev, “which was against the law.” The situation was comparable to current nudity standards imposed by Instagram and Facebook, nourishing vapid content. But artists are a resilient bunch. Like weeds through asphalt, they’ll carve a path to daylight.

While Soviet proscriptions limited Bakharev, they also presented an opportunity. For certain portrait subjects, his camera offered a chance to buck the system, and to embrace a disencumbered expression of their identity. “As for freedom,” Bakharev once told an interviewer, “it stays inside people just as it stayed there before. You just have to win their confidence and leave their inner morality unviolated.” He found many willing sitters exemplifying the full spectrum of liberation. For raw exhibitionism, readers should seek out Novokuznetsk. Cheryomushki is the quietly life-affirming counterpart.

The book includes fifty monochromes. Most of photographs are square format, with a few oblong frames sprinkled in the mix. This is the only slight variance in a steady drumbeat of photos of equal size and layout. Each spread shows one image on the right-facing page, all well printed with lush tonality. The pacing of pictures is as regular as a metronome. Tick tock tick… As the reader is lulled into a relaxed daze, the photos gradually work their cumulative spell. They convey a spirit of companionship, satisfaction, and pride.

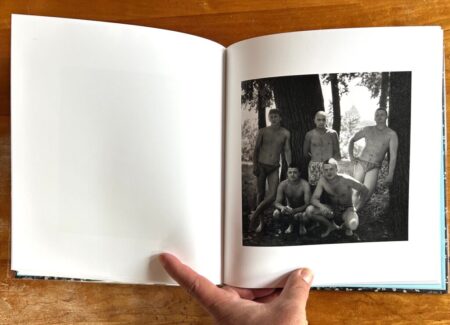

In contrast to Novokuznetsk, the demographic here is more expansive, with a wide mix of gender, age, fitness, and group size. Some are romantic couples or friends on an outing. Other frames capture families or coworkers or leisure buddies. Perhaps some are fresh acquaintances pulled together for a quick photo op before parting again.

A handful of photographs depict solitary figures, but the vast majority join multiple people together. Almost without exception, Bakhavev’s subjects are connected through human touch. They hug, embrace, lean, or just hold hands. A middle aged couple spoons comfortably against each other in one photo, with the woman’s arms circling the man’s face. Another shot captures a group of bare chested men lazing in the grass, arms entwined in a six-part pretzel. In another photo, Bakharev captures a naked young couple in flagrante during foreplay. Viewed cumulatively, arms, hands, and fingers join people, pages, and the book itself.

With no captions or context, the situational specifics are anyone’s guess. But there’s no doubting Bakharev’s sure handed mastery, which provides the connective glue. Encountered in swim gear, his subjects have already been partially disrobed. Bakharev strips them down further to their emotional core, probing below the skin-deep surface to crack the inner shell. Humanity peers into his lens with equanimity, as if gazing in the morning mirror. I have rarely encountered a portrait book with strangers so present, vulnerable, and fully open to the camera. Judith Joy Ross comes to mind, along with Mike Disfarmer and Diane Arbus.

As with these others, Bakharev’s process is mysterious. Who knows how such portraits happen? Perhaps he learned how to befriend strangers as a young orphan, or maybe he polished his interpersonal skills in the factory, or on assignment? Maybe it is just innate talent? Perhaps Siberian culture fosters physical contact? It is tantalizing to speculate, but the proof is in the pudding. “There must be a mutual relationship,” Bakharev says about his process. “They need to understand that I am not watching my sitters—it’s as if I’m part of the picture… A picture should not be beautiful, but interesting, then you can find beauty. Beauty is in the human relationships that are formed.”

Bakharev’s portraits would be remarkable in any context. But the fact that he made them inside a restrictive and collapsing empire makes them more impressive. Soviet laws and Siberian removal were mere speed bumps for Bakharev, and Perestroika a passing road sign. As global players flirt with authoritarian impulses in the present day—including in my own country, the United States—Cheryomushki is a helpful reminder that the human spirit is not easily vanquished. With diligence and skill, photographers can find it just about anywhere, poking up through the rules like a seedling.

Collector’s POV: While Nikolay Bakharev has had gallery representation in the past, those relationships seem to have lapsed, and his work has only been intermittently available in the secondary markets over the past decade. For collectors interested in following up, this likely leaves the publisher Stanley/Barker (linked in the sidebar), who may be able to assist in making a connection.