JTF (just the facts): A total of 25 black-and-white and color photographs, framed in white and unmatted, and hung against white walls in the main gallery space and the entry area on the ground floor. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

- 4 gelatin silver prints, 2025, sized roughly 25×21 inches, unique

- 21 dye transfer prints, 2025, sized roughly 20×15 inches, unique

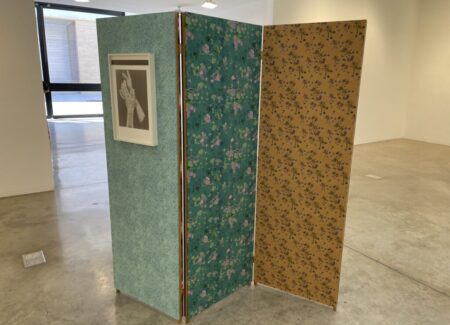

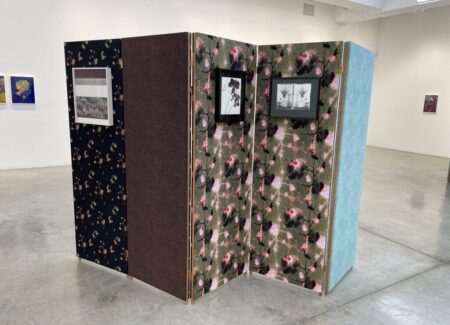

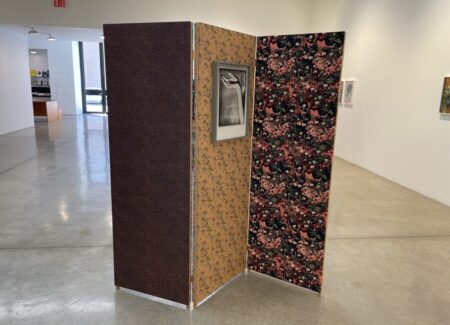

- 1 three-paneled paravent with 2 attached gelatin silver prints, 2025, sized roughly 73×71 inches

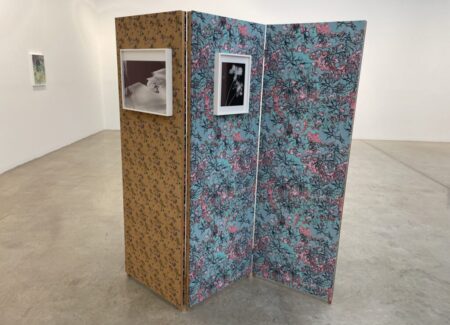

- 1 three-paneled paravent with 3 attached gelatin silver prints, 2025, sized roughly 72×71 inches

- 1 five-paneled paravent with 5 attached gelatin silver prints, 2025, sized roughly 72×119 inches

Comments/Context: In thinking about Lisa Oppenheim’s work across the past decade or so, there’s probably a Venn diagram to be drawn that might help explain some of the layering of her consistent interests. One circle might contain the history of photography; the next could include a commitment to experimentation with photographic processes; the third might house an interest in antique or historic textiles of different kinds; and the fourth could bring in flowers and floral patterns. And while not all of her shows, projects, or bodies of work can be entirely located in the overlapped intersection of these various themes and ideas, such an orienting diagram would certainly cover enough of her conceptual landscape to be useful.

Oppenheim’s newest project settles into the sweet spot of this hypothetical Venn diagram, centering her attention on Edward Steichen. For regular readers here, Steichen likely needs very little introduction, his long photographic resume speaking for itself – aerial photo specialist during World War I, Condé Nast chief photographer (with both Vogue and Vanity Fair under his wing), MoMA photography curator, and organizer of “The Family of Man” exhibit, among other notable achievements. Buried in this biography are two other line items that directly connect back to Oppenheim’s own artistic practice – Steichen used photography to design textile patterns for Stehli Silks, and he was an accomplished amateur flower breeder.

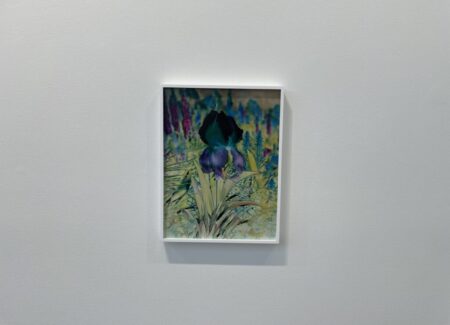

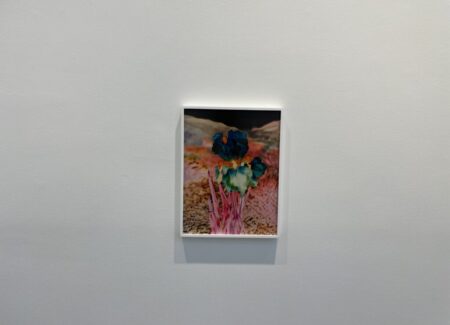

With these tantalizing (and lesser known) biographical details as clues, Oppenheim dug back into Steichen’s history, looking for potential entry points for further artistic exploration. Following Steichen’s flower breeding trail, she uncovered an iris variety that had been named “Monsieur Steichen” (in Steichen’s honor) by another amateur botanist back in 1910. But there were two problems: there were no photographs of the flower, and no living specimens to be found anywhere. Oppenheim was able to track down the two varieties of iris that were originally the genetic parents of the “Monsieur Steichen” iris, and so she embarked on an effort to re-imagine what the iris variant looked like, using AI to hybridize available images of the parent species.

This approach ultimately yielded seven different variant images of the elusive Steichen iris (as seen in this show), each one given a different prefix by Oppenheim (including Mme, Mlle, Frau, Madamm, and others). As images of “impossible” flowers, the works fall into a long line of artificial and constructed floral compositions across the history of the medium (Joan Fontcuberta’s being perhaps the most notable). And while the AI system did make some decisions and extrapolations about the possibilities of petal shape and configuration, it didn’t take many risks with the overall framing or composition of the “photographs” – the plants are shown straight on, isolated in natural settings, some with a hint of horizon in the background.

To make photographic prints of these images, Oppenheim decided to turn the artistic crank a notch or two further. Not only did she decide to print them using the dye transfer process – a process that Steichen himself had used in the 1930s and 1940s, which has slowly fallen out of broader usage, given the discontinuation of many of the original Kodak materials back in the 1990s – she tweaked the underlying color palettes far out of their usual ranges, creating multiple variants with “incorrect” color combinations (a broader idea systematically explored in the work of Jessica Eaton). The resulting floral portraits drift into seething oranges, reversed pinks, icy greens, deep purples, and fiery reds, each image printed in more than a dozen unique looks, only a few of which are on view in this installation. Without knowing the backstory, we might assume that these florals are simply exercises in iterative color manipulation, with tonal ranges pushed toward brash psychedelic limits; with a bit more context, Oppenheim’s works represent an innovative homage to Steichen, remixed and re-imagined with a clever combination of old and new photographic technologies.

In the center of this gallery installation, Oppenheim has staged three multi-panel screens or paravents. These works connect back to Steichen’s efforts in fabric design, in collaboration with Stehli Silks back in the 1920s and 19930s. Oppenheim combed through Steichen’s archives and unearthed a number of images he made but didn’t actually use for textiles, and in collaboration with the fashion designer Zoe Latta, Oppenheim created several new fabrics from Steichen’s original pictures – and it is these fabrics that cover the paravents. Most of the new designs create repeating patterns of florals or tactile swaths of gravel, in a range of colors. One standout pattern features a brash mix of pink and light blue, the curved edges of Oppenheim’s digital manipulation of the underlying florals altogether visible.

The paravents also provide handy space for the display of a few additional photographs. These black-and-white works were largely made by Oppenheim while working in the Steichen archives, as reprints of Steichen images she found there or stills of florals on display nearby. She then went back to her own darkroom and made several more floral images (and photograms) inspired by Steichen’s examples, creating yet another layer of thoughtful rework and re-interpretation. In this way, the paravents feel nested, with Oppenheim working inside Steichen, bringing her own artistic perspective to his world, and again, knowledge of the backstory enriches the interpretation of the resulting objects.

As always with Oppenheim, there is a clear conceptual logic here that provides a foundation for her artistic choices and experiments. While chance and exploration are part of her process, they take place within a framework of intellectual rigor that bounds the possibilities. In this way, Oppenheim’s works can be enjoyed on the basis of their surfaces, but more often encourage deeper explanation and reasoning, the “what” of the images leading directly back to the “why”. Many of her Steichen-inspired florals are boldly eye-catching, but it’s Oppenheim’s underlying train of thought and action that ultimately gives them a deeper sense of sophistication.

Collector’s POV: The works in this show are priced as follows. The dye transfer prints are $12000 each, the gelatin silver prints are $14000 each, and the paravents are priced at $35000 or $45000, based on size. Oppenheim’s works have begun to slowly enter the secondary markets in recent years, but there have been too few transactions to reliably chart any price pattern. As a result, gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.