JTF (just the facts): A total of 54 color photographs, alternately framed in black and unmatted or framed in brown wood and matted, and hung against white, light green, and dark grey walls in a series of rooms on the first floor of the museum. The exhibition was organized by Jody Graf. (Installation shots below.)

The following works have been included in the show:

- 18 digital inkjet prints (from “Keepers of the Ocean”), 2019, sized roughly 8×5, 16×24, 24×16, 33×50, 50×33 inches

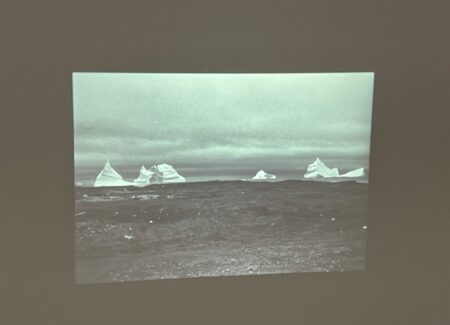

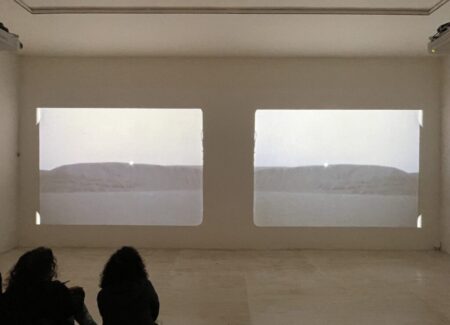

- 1 35mm slide projection (80 images), 2018, dimensions variable

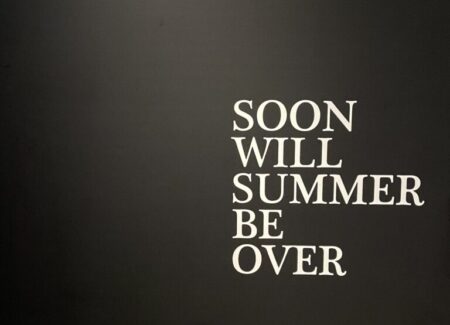

- 18 digital inkjet prints (from “Soon Will Summer Be Over”), 2023, sized roughly 8×5, 24×16, 30×30, 50×33 inches

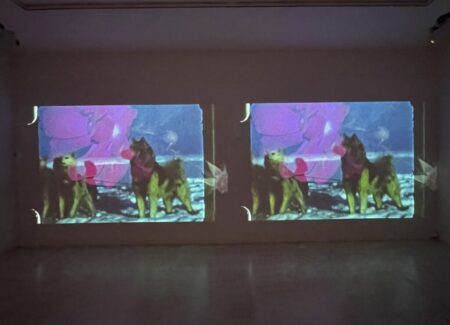

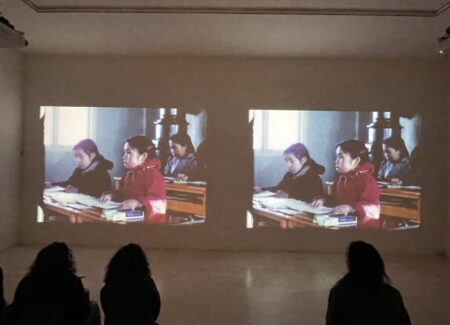

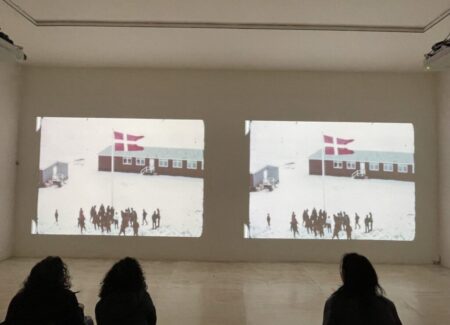

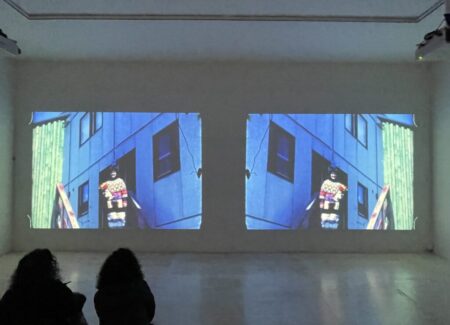

- 1 two-channel video (color, sound), 2016-2022, 11 minutes 26 seconds

- 18 digital inkjet prints (from “What if You Were My Sabine?”), 2025, sized roughly 8×5, 24×16, 30×30, 50×33 inches

Comments/Context: While museum exhibitions tend to be planned years prior to when they actually find their way to the gallery walls, there is an uncanny timeliness to the arrival at MoMA PS1 of Inuuteq Storch’s first solo museum show in the United States. Storch is a native of Kalaallit Nunaat (or Greenland as it is known in English), and earlier this year, the Trump administration amplified its interest in buying the island from Denmark, simultaneously introducing an intense dose of blustering power play into the region’s politics and resurfacing ongoing questions of colonial intervention in the independent lives of Greenlanders. As vice president JD Vance toured the island on a photo op, theories about what the population of the territory really thinks (or wants) started to emerge, mostly voiced by pundits and outsiders. As a counterpoint to those external conjectures, Storch offers a compelling but little seen example of the actual Greenland gaze – a talented photographer from Greenland making (and rediscovering) images of the everyday life of Greenlanders (of both Inuit and European heritage), seen on their own terms.

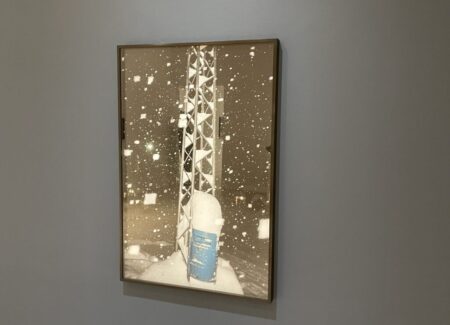

This compact survey skips through Storch’s work in the past decade, diving into three successive photographic projects and two separate investigations of archival imagery from his homeland. The earliest images on view come from his 2019 project “Keepers of the Ocean” (which took form as a 2022 photobook, reviewed here). Storch’s aesthetic style is easy going, candid, and intimate, with a relaxed sense of being present and paying attention. Given the extreme environment and its seasonal variations, it isn’t entirely surprising that the rhythms of life in his hometown of Sisimiut (just north of the Arctic Circle) seem to be divided between inside and outside. Inside, we feel the closeness of snow boots hanging in the hall, key rings on a board, clutter on the dining room table, and a lantern in the window, with the gestures of relationships captured as the interlocked arms of a hug, a cuddled embrace on a couch, and the quiet touch of bodies. Outside, Storch mixes snippets of youth culture – beers discarded in a pile near the roadside, a cluster of young people hanging out around a yellow truck at night, the name of a local rock band graffitied on a wall, and a young man lying in a bed of flowers – with the community routines of drying the laundry, playing with the sled dogs, smoking a pipe, and taking out the trash. A bit of bright flash animates Storch’s scenes in both places, with a nighttime image of falling snow drifting around a metal tower transformed into glittering magic.

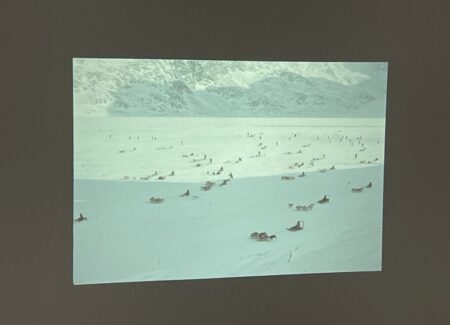

In the summer of 2023, Storch ventured even further north, to Qaanaaq, the northernmost town in Greenland. A dramatic view from above situates the outpost at the edge of the iced-over bay, making it clear that we have moved somewhere even more remote and extreme than Sisimiut, with thick ice covering the surfaces of land and sea and the midnight sun filling the sky from April through August. Storch’s resulting project “Soon Will Summer Be Over” applies a sensitive eye to the lives being led here, with the inside/outside duality from his earlier work now applied to a different set of daily realities. In the warm months of the summer, hunting seals and narwhals dominates the days, and Storch’s pictures circle around the process, watching as preparations are made, dogs are readied, and wooden harpoons are whittled and shaped, these traditional activities then balanced by aftermath images of men carving up the kill, filleting slabs of meat and blubber, and leaving a slick mess of blood on the ice; while the parents and elders may be feeling the pressures and anxieties of climate change as this world is being transformed, the kids seem less bothered, seemingly enjoying the simple pleasure of lying out in the relative warmth of the summer sun.

When Storch heads inside people’s homes, he repeatedly notices the subtle cultural clash (or perhaps hybridization is a better way to think about it) taking place in the assembled decor. Honored harpoons, old family photos, pieces of nature, sketches of the land, and even a framed narwhal tusk are the kinds of things we might expect to find in this community, but there are just as many string lights, paper hearts, shiny curtains, and pictures of Jesus, the traditional and the modern often swirled into artistic assemblages of images and objects that cover entire walls; and if you were wondering, even “Live Love Laugh” has found its way to farthest reaches of the north country. Storch also continues his nuanced observations of bodies and poses in these pictures, noticing a lineup of kids along a stairway railing, the hand of a smoking man, the matching tattoos of a couple (from 1960), and the comfortable presence of those found at kitchen tables, near windows, and feeding babies. As a project, the images feel less youthfully brash and more understatedly respectful, with Storch valuing the way these lives are being led, even if they are somewhat different than his own.

Storch’s most recent project takes a turn toward the personally romantic, the photographs in “What if You Were My Sabine” (the title likely a nod to the Danish photographer Jacob Aue Sobol’s 2004 photobook Sabine, which was also shot in Greenland) made with the consistent tenderness and measured grace of a valentine. Several images send a message of warmth, as seen in the reflected afternoon glow in windows, the welcoming light in a house on a dark snowy night, and an improvised self-portrait shadow overlooking the town. Other pictures reflect care and commitment – a tattoo on a neck, a graffitied symbol on rocks, a screen shot of a ballet dance, a map on the wall, and other gifts and celebrations in the form of holiday bunting, a bird tied in ribbon being presented upside down, and more obscure altar-like hanging arrangements of objects. Even the harshness of the winter is softened by Storch’s attention, as delicate ice crystals on window panes and flickering snow flying through the night. Only the consistent bleakness of the concrete housing blocks (built by the Danish government to relocate Inuit communities) dampens the overall mood, with smokestacks and sheds overflowing with junk a simmering reminder of the grim constraints imposed by contemporary existence.

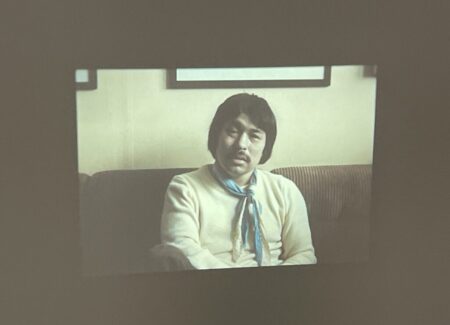

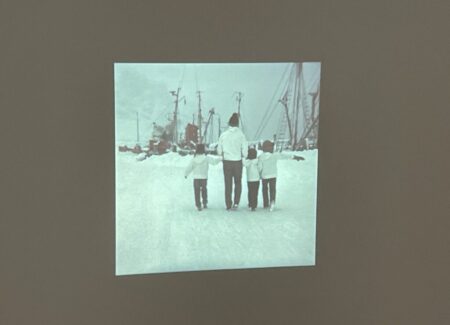

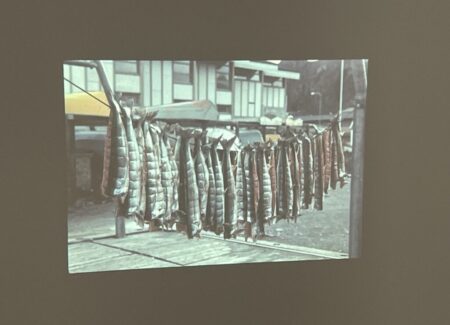

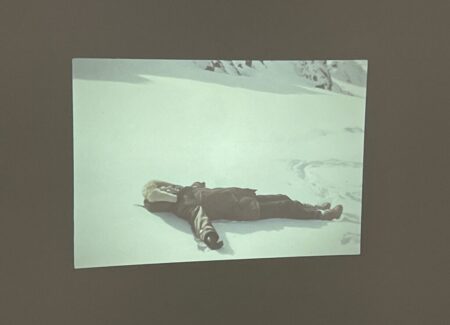

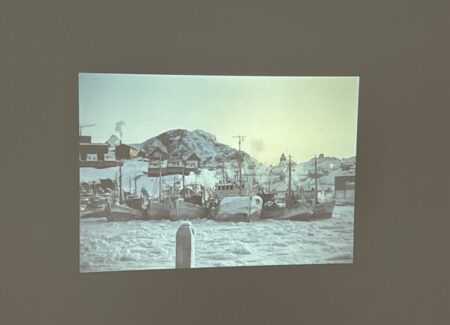

Any photographic search for identity, like the one Storch has embarked upon, benefits from some historical context, and between his personal artistic projects, he has also been busy assembling archival photographs and home movies from around Greenland, in the attempt to construct a broader visual history as seen by the native population. Here he has presented a slideshow of images made by his parents between the 1960s and 1980s and a video work assembling clips of everything from the visits of Danish royalty to school children and brides in traditional sweaters. In particular, the family snapshots are peppered with vernacular gems, from racing sled dogs and snow angels to ice-bound boats and hanging fish. What’s important about these works is that they complement Storch’s own vantage point, giving us a shared visual history to measure his artistic perspectives against, instead of the misinformed stereotypes we might have brought with us to the museum.

As a succinct but memorable summation of Storch’s work over the past decade and an introduction to his unique artistic voice, this first museum exhibit lays the foundation for what we can expect to be a photographic career worth tracking. In persistently seeking an individual path as an artist proudly from Greenland, his images have become more and more personal, their casual charm partially obscuring a sophisticated aesthetic sense for the enchantment of a passing moment. To date, while there are plenty of people to be found in Storch’s photographs, he hasn’t yet laid bare his engagement with them (in a Nan Goldin kind of way), often opting for a more oblique angle into the interactions. There is an even riskier artistic road that lays in that kind of engaged picture making, but it may well be the approach that ultimately pushes Storch to the next level. His world will almost certainly come under further pressures in the coming years, and it is those building tensions and emotions that he is well placed to show us.

Collector’s POV: Inuuteq Storch is represented by Wilson Saplana Gallery in Copenhagen (here). Storch’s work has little secondary market history at this point, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.