JTF (just the facts): A single project-centric exhibition of photographs and related ephemera, installed against red walls in a series of divided spaces on the main floor of the museum. The exhibit was curated by Antonio Sergio Bessa. (Installation shots below.)

The following works are included in the show:

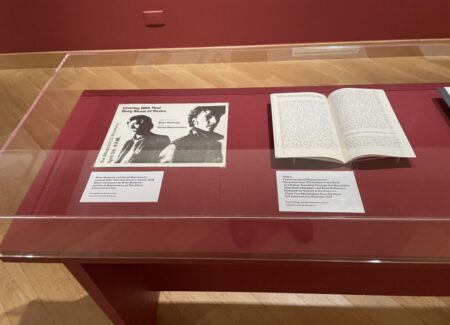

- (vitrine): 1 paperback book (by Arthur Rimbaud)

- 1 gelatin silver print, c1980

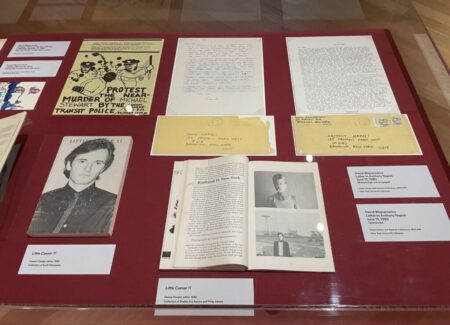

- (vitrine): 1 flyer, 1978; 1 self-published magazine, 1979, 1 offset book, 1982

- 1 gelatin silver print, 1980

- 5 gelatin silver prints, 1978/2004

- 24 gelatin silver prints, 1978-1979/2004

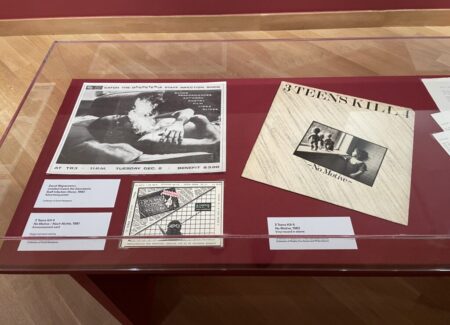

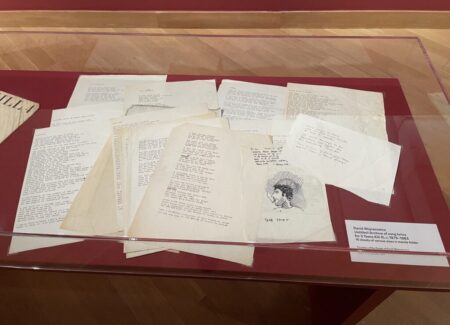

- (vitrine): 1 poster, 1980; 1 announcement card, 1980/1981; 1 vinyl record sleeve, 1982; 16 sheets of song lyrics, c1979-1983

- 1 newspaper, 1980; 1 newspaper spread, 1980

- 2 gelatin silver prints, 1978-1979

- 15 gelatin silver prints, 1978/1990

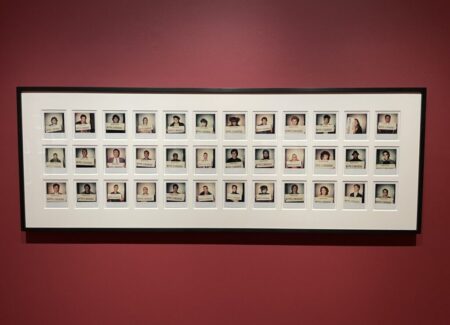

- 1 set of 36 Polaroids, 1980

- 15 gelatin silver prints, 1980

- 18 gelatin silver prints, 1980

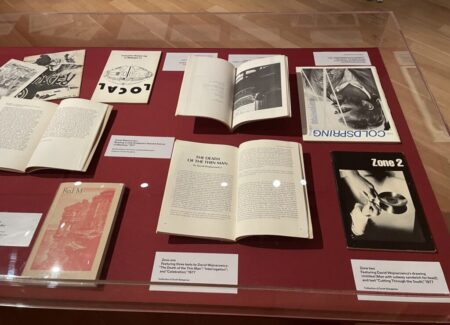

- (vitrine): 3 photocopy sheets, 1977; 1 offset book, 1977; 2 offset books, 1977; 1 journal, 1977; 2 offset books, 1977; 4 photocopy books, 1977

- 1 poster, 1981

- 1 drawing, 1981

- 1 gelatin silver print (Peter Hujar), c1983

- 1 gelatin silver print (Marion Scemama), n.d.

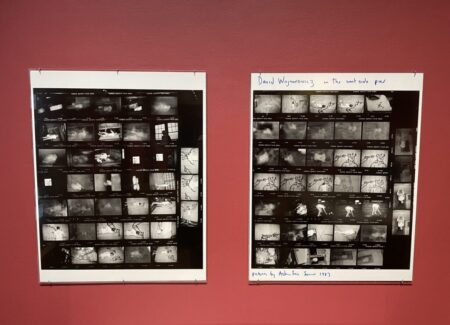

- 2 gelatin silver print contact sheets (Adam Fuss), c1983

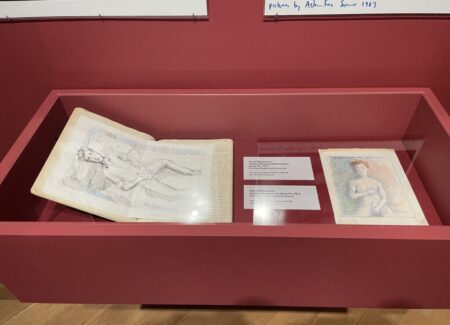

- (vitrine): 2 drawings on paper, 1979

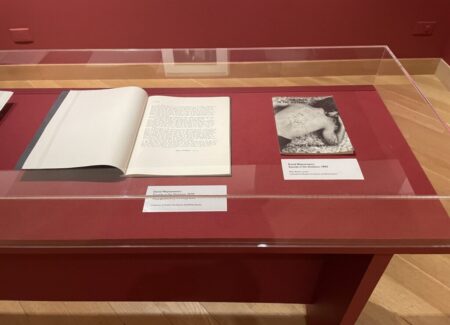

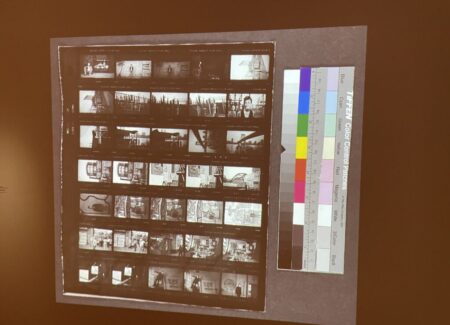

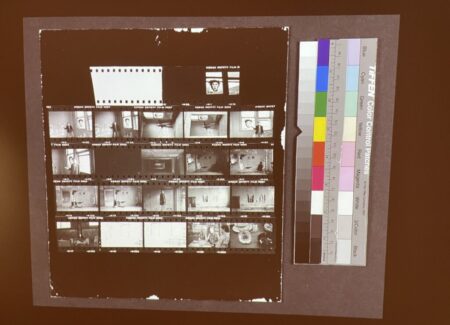

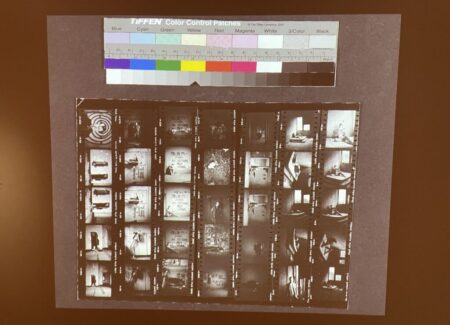

- (slideshow): contact sheets

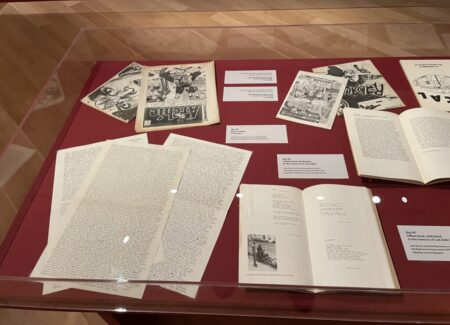

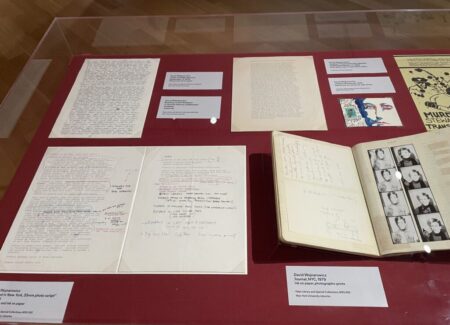

- (vitrine): 2 pages typescript, n.d.; 1 journal 1979; 1 letter, 1979; 1 typescript page, n.d.; 1 felt tip pen on card stock, 1979; 2 offset book, 1980s; 1 flyer, 1983; 2 letters, 1980

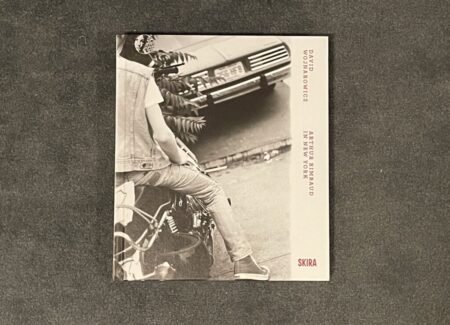

A catalog of the exhibition has been published by Skira (here). Hardcover, 9.5 x 11 inches, 208 pages, with 150 reproductions. Includes essays by Antonio Sergio Bessa, Stamatina Gregory, Nicholas Martin, Anna Vitale, Craig Dworkin, Fiona Anderson, and Marguerite Van Cook, and a foreword by Philip Aarons. (C0over shot below.)

Comments/Context: For nearly every person who has been labeled a “New York artist” of one kind or another, the struggle to artistically come to grips with the rich complexity of New York City never really drifts far from view. Often this process of engagement takes shape as a pitched battle between feeling in and out, between finding a way to connect to the sprawling energy of the city in some unique and meaningful manner, while at the same time attempting to discover a sense of singular personal identity within its many geographies, subcultures, and contradictions. The not-so-easy questions of who am I and what is this city naturally get intermingled, particularly for younger artists, and making art that actively responds to the pulse of the city can thus become a process of brashly inserting oneself into its flowing currents and creatively rooting around, continually searching for expressions that both reflect the artist’s authentic personality and meet the larger artistic moment.

The 1970s were a particularly rough decade in the long history of New York City. It was a period of gradual societal decay, with the economy in decline, crime and drug use on the rise, and a feeling of gritty hopelessness settling over the streets, the situation worsening after the riots and looting during the blackout in 1977. And for much of this unsettled period, a young David Wojnarowicz (born in 1954) was living on those very same streets, at times working as a queer street hustler near Times Square. In 1978, he took a trip to Paris and Normandy to visit his sister, and while he was there, he fell under the spell of the 19th century French poet Arthur Rimbaud, who himself had been a teenage runaway and a youthful rebel. When Wojnarowicz returned to New York later that year, the inspiration he drew from Rimbaud’s spirit seemed to tag along, and once he was home, Wojnarowicz saw the parallels between Rimbaud’s life and his own downtrodden urban existence even more fully. It was then that he began what would become one the landmark projects of his artistic life, a series of photographs titled “Arthur Rimbaud in New York”, and the subject of this single body of work deep dive exhibition.

In the years since his death in 1992, Wojnarowicz has been rightly recognized as a kind of artistic polymath, with wide ranging interests and talents that included painting, writing (in the form of books, poems, essays, monologues, and journaling, among others), sculpture, installation, performance, photography, and political activism/social critique, particularly during the most intense years of the AIDS crisis and in the rejection of artistic censorship. A 2018 retrospective at the Whitney (reviewed here) ably took stock of many of these diverse pursuits, but such a survey has only so much room to explore the depths of any one artistic idea. This museum show picks up Wojnarowicz’s early Rimbaud thread and methodically follows it much further, offering a thorough and definitive explication of the now iconic photographic project.

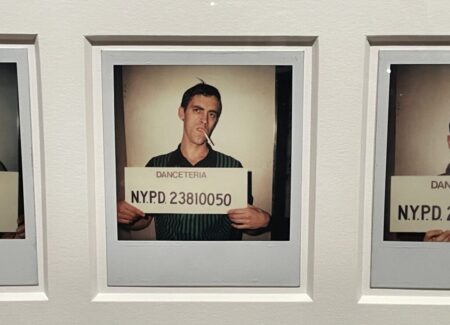

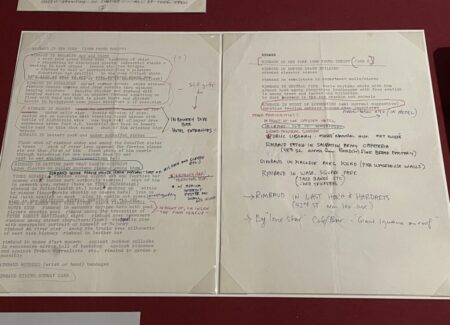

The conceptual structure of “Arthur Rimbaud in New York” is relatively straightforward. Wojnarowicz took the head shot cover image from Rimbaud’s 1966 book Illuminations (a copy of which is on display in a vitrine at the start of the show), enlarged it to life size, placed it on a paper mask with small cutouts for the eyes and mouth, and then asked friends to pose wearing the mask at various places around the city. In the period between 1978 and 1980, Wojnarowicz took some five hundred masked images around town (many of the original contact sheets are on view in a digital slideshow), the strongest of which he eventually edited down to a more manageable group. The series was first exhibited in 1990 at PPOW Gallery as a selection of 25 images, and was later (in 2004) issued as a somewhat larger posthumous portfolio of 44 photographs. This show includes examples from both edits, as well as a number of rare vintage prints and test prints (most made by Wojnarowicz himself in 1980), offering the opportunity to compare different prints of the same image from different time periods.

The idea of bringing Rimbaud to 1970s New York and taking him around to the places that meant something to Wojnarowicz, like a friend from out of town, has a kind of searching kinship and endearing romance to it. For many in the downtown scene, including the musician Patti Smith, Rimbaud became a kind of cult figure, so much so that Marguerite Van Cook would later call Rimbaud “the proto-punk grandfather of the East Village.” As seen in his detailed planning notes, Wojnarowicz had a wide range of places he wanted to pose his friends wearing the Rimbaud mask, the whole concept seeming to gain its own momentum the more places he went. Rimbaud could be a tourist, but he could also be something like a local, with his same alienated rebel swagger, thereby indirectly embodying many of the same emotions and impulses that Wojnarowicz himself was feeling.

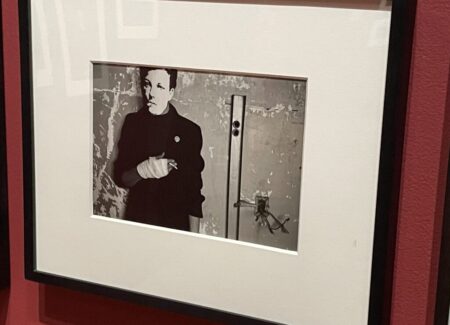

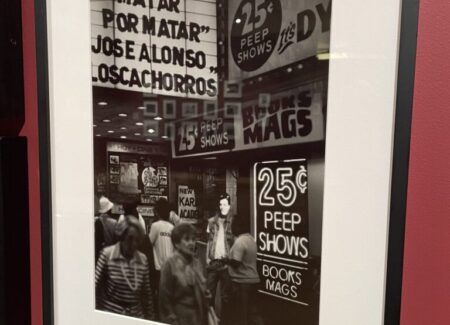

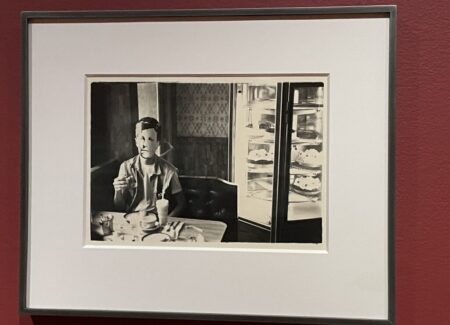

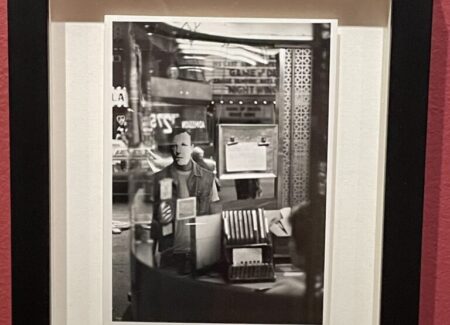

Placing Rimbaud on the beach near the carnival attractions at Coney Island or underneath the Brooklyn Bridge feels almost perfunctory, like checking off the spots he was supposed to visit. But as he slides further into Wojnarowicz’s life, things get much more interesting. He hangs out in diners (reading a newspaper or having a milkshake near a cake display), lingers on the streets near shop windows and neon-lit bars, stands near Times Square peep show theaters and a movie ticket kiosk, and rides the subway like any other New Yorker. But of course, placing the masked Rimbaud in these everyday places was entirely performative, inserting a particular presence into the flow of life and watching what might happen next. In many images, Rimbaud seems almost hyper real, sticking out from the surroundings; in others, that separation feels poignantly lonely, like an outsider with little hope of fitting in.

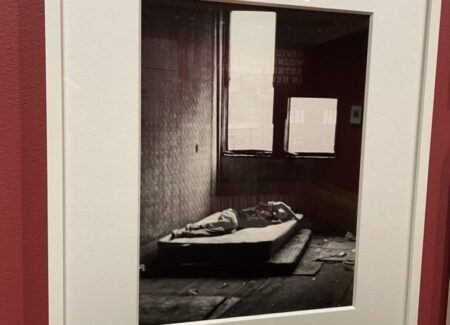

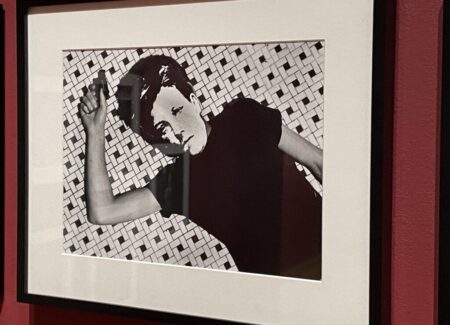

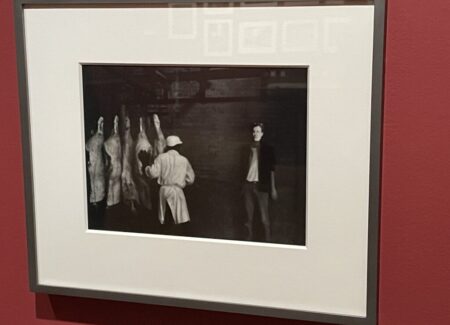

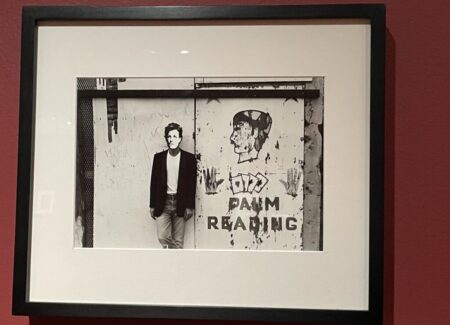

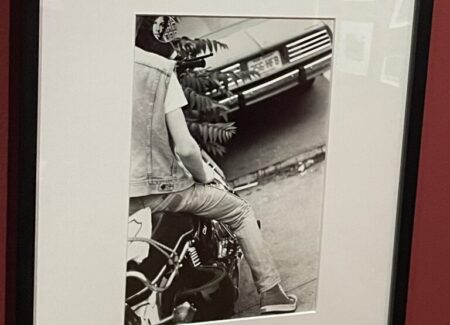

Wojnarowicz channels Rimbaud’s irreverent rebel persona in plenty of setups, from posing him on motorcycles (one featuring a clever reflection in the side mirror) to having him play with handguns (leading to his splayed body on a tile floor, the handgun still in his hand). Soon he’s hanging out with the meatpackers and their bloody carcasses, posing with a palm reader’s mural, and sporting a bandaged hand from some unexplained injury. The mood quickly turns darker as we find Rimbaud smoking a cigarette in a tank top, lying on a dirty mattress in a sordid squat, posing near shadowed windows, peeing in a dank toilet, and shooting up with a needle in his arm. Several heroin-themed Rimbaud images are sprinkled through the show, some ultimately illustrating a 1980 story about the drug’s popularity in the Soho Weekly News.

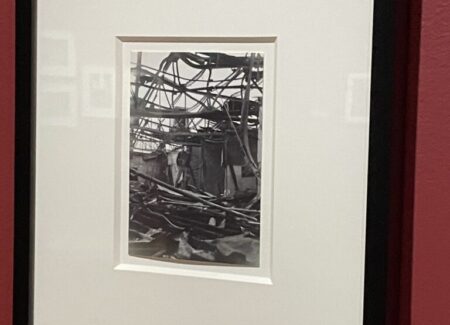

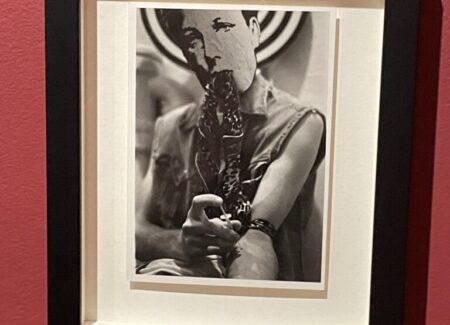

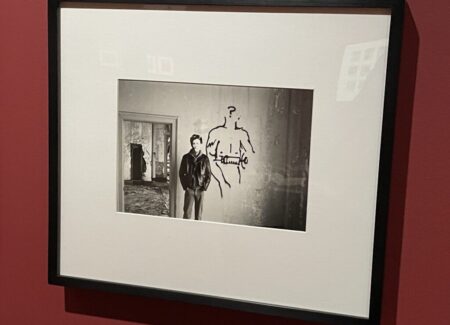

Another recurring theme in the series finds Wojnarowicz posing Rimbaud in the abandoned warehouses on the piers near the West Side Highway, a popular cruising ground for gay men at that time. Rimbaud settles into the crumbing rooms with understated style, playfully engaging with the graffiti sprayed on the walls and windows, climbing out of a decayed hole in one wall, standing amidst an ominous thicket of sagging girders, and lying against the rough texture of rotted black roofing. This was a place that Wojnarowicz frequented, and the Rimbaud avatar seemingly feels at home in its empty but charged (and sometimes dangerous) atmosphere. Still other images find Wojnarowicz becoming more compositionally inventive. One picture features Rimbaud near what appears to be a musical chicken, while another stages him in a spray painted spiral, like he’s emerging from the Twilight Zone. Jesus also makes an appearance on a painted wall, his welcoming outstretched arm mimicked by Rimbaud.

Seen across the entire body of work, the masked figure of Rimbaud starts to feel almost universal – ostensibly a particular appropriated identity but actually anonymous, making room for us to insert ourselves into Wojnarowicz’s setups. The French poet and his vacant stare have been thoughtfully placed into the grimy urban fabric of the city, but he’s most often somewhat separate from that world, an outlaw or an outcast, in an almost defiantly cool way that seems to reaffirm his presence. While there is no cohesive narrative that connects the pictures from “Arthur Rimbaud in New York” into a single story, the whole project feels like a self-examining mirror for Wojnarowicz, one where he actively wrestles with parts of his own identity, but also one where anyone can be Rimbaud. Self-exposure and theatrical performance become two sides of the same coin, where the paper mask of a hero becomes an enabling prop for examining the contours of life in the city for a young gay man in the 1970s.

Part of what makes the images from “Arthur Rimbaud in New York” so enduringly powerful is this active tension between the private and the public, and the way the Rimbaud mask transforms the available artistic possibilities. As with Ralph Eugene Meatyard’s images made with members of his family wearing dime store rubber masks in the late 1950s, Wojnarowicz’s photographs mix a surreally incisive wit with sensitive tenderness. The city around him may be in ruins, but the Rimbaud figure finds a way to survive, like a beacon to those who might be intimidated by their own constrained lives. It is this understated optimism that feels quietly contagious; long before Wojnarowicz became a passionately vocal and persuasive activist, this project signaled a growing confidence in his own point of view. These photographs have aged well because Wojnarowicz taps into the individual heroism of the New York hustle, viscerally reminding us of what it feels like to be young in New York City and fighting to find yourself.

Collector’s POV: Since this is a museum exhibition, there are of course no posted prices. The estate of David Wojnarowicz is represented by PPOW Gallery in New York (here). Wojnarowicz’ photographic/collage works have appeared only intermittently at auction in the past decade. Recent prices have ranged from roughly $5000 to $940000.