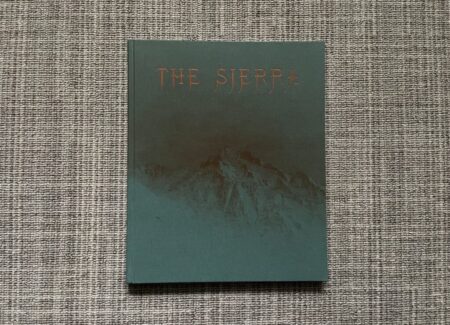

JTF (just the facts): Published in 2025 by The Eriskay Connection (here). Hardcover, 240×292 mm, 112 pages, with 50 color reproductions. Includes an essay by Leah Ollman, a quote by William Cronon, and a short text by the artist. Design by Rob van Hoesel. In an edition of 800 copies. (Cover and spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: It’s a little bit scary to reflect on the idea that not so long ago we thought about climate change in an entirely anticipatory, forward-looking manner. It was something that was going to happen, that we could see coming, and that would affect our collective futures if we didn’t act thoughtfully and urgently, but its actual effects were largely over the horizon somewhere. Of course, the years have continued to click by, and suddenly (or not so suddenly) we find ourselves not only with an increasingly menacing climate future ahead of us, but with very real climate impacts taking place in the present, and enough road behind us to recognize the many climate change realities in our own pasts. For each and every one of us, this tripled past/present/future of changes is forcing us to renegotiate our long established relationship with whatever natural places and landscapes that we hold dear – we remember them how they were, witness them as they are now, and wonder about what they might look and feel like in the future, all at the same time. This time-collapsed observational framework is making the abstraction of climate change much more personal and experiential.

Aaron Rothman’s photobook The Sierra is the first climate change-themed project I have seen that actively wrestles with this intimately layered seeing process – it doesn’t just show us melted icebergs or dry lake beds, but artistically creates a wider context of time. Rothman has been visiting the Sierra Nevada mountains in California since he was a teenager, and over a period of roughly six years (since his 2018 photobook Signal Noise, reviewed here), he returned to many of those familiar places and ventured out to plenty of new ones, making landscape images with his 4×5 camera. It is this repetition, this sense of seeing a cherished place again and noticing how it is changing, matching memory against present experience (and future imagination), that thrums within his pictures.

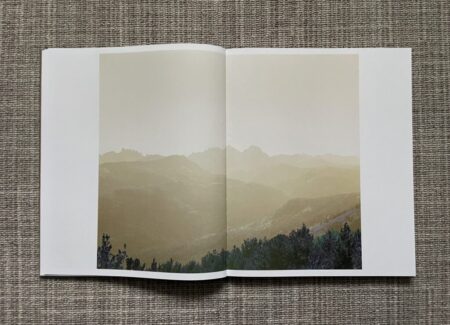

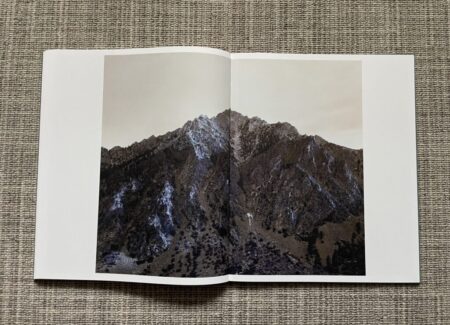

Rothman’s process is a 21st century blend of old and new. He starts out in an old school 19th century surveyor style, toting his film camera up into the mountains to make painstaking large format exposures of elegant vistas, craggy peaks, dense forests, and artfully framed single tree specimens. But he finishes in a sophisticated computational photography mode, manipulating most of the images digitally, interpreting them in a manner that echoes the way Ansel Adams “played” his negatives in the darkroom like a musical score. His results range from essentially straight unaltered landscapes to eerily color tweaked impressions and fabrications, each one settling into a fluid continuum between what is and what might be. In several cases, his manipulations are so deft that it’s hard to identify them, making the whole idea of what might be “real” in this climate transformed world that much more subtly uncertain.

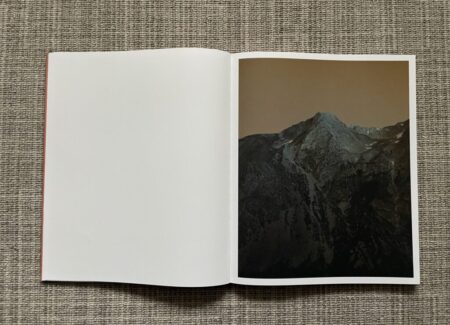

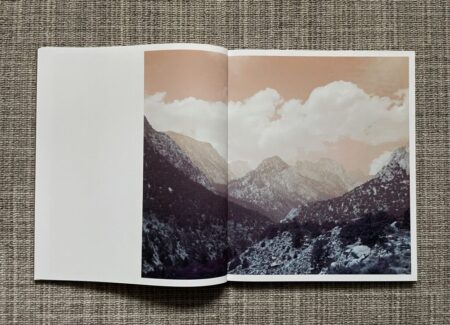

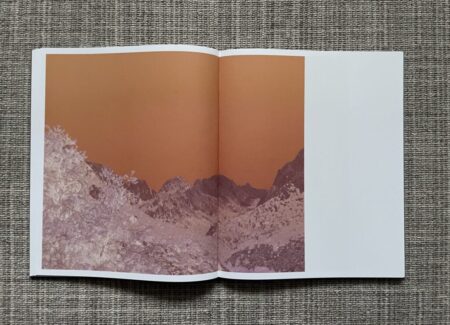

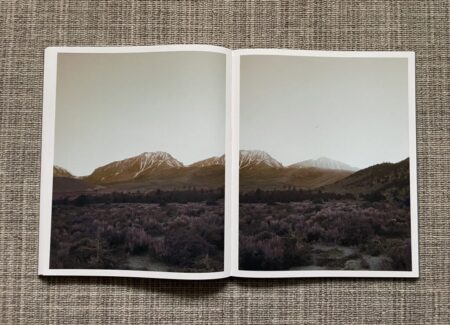

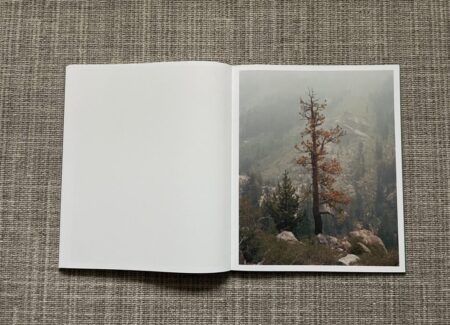

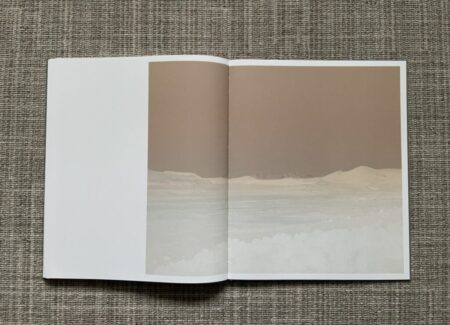

It’s clear that Rothman is well aware of the stylistic and compositional approaches that were traditionally used to depict the American wilderness landscape by photographers like Eadweard Muybridge and Carleton Watkins and painters like Albert Bierstadt. In many ways, his views pay homage to what came before in terms of framing or location, in a sense reaching back in time to reconsider what those earlier artists documented. But even when Rothman has created a throwback setup with a majestic sweep of mountains or a lone pine unbalancing a scene that overtly triggers our memories of such places, it’s hard not to be swept into the present. Thick whiteness fills valleys, blocks peaks, and envelops views, making them hardly visible, the wildfire smoke choking off their familiarity. In the moments when then the haze has actually lifted (which isn’t all that often), the dryness of the rocky peaks becomes all too clear, the dirt parched to thirsty dust and the snowcaps all but gone. The artfully framed trees we are accustomed to seeing are charred to blackness in Rothman’s world, or simply weakened by drought to the point that the evergreen needles have turned a sickly orange and the trees are on the verge of death. Of course, haze in the twilight air can make the colors of a sunset look even more softly beautiful and dramatic, but in this case, the resulting feeling is much more conflicted and vulnerable.

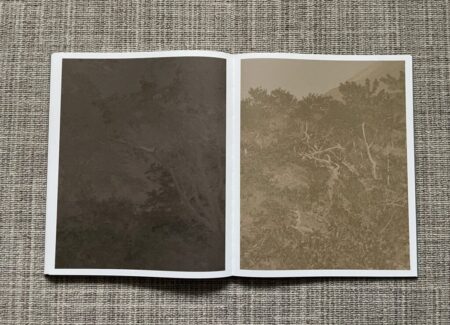

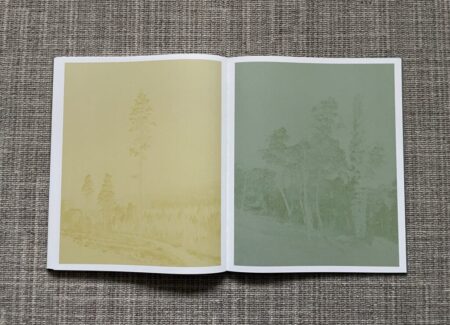

Rothman isn’t the first photographer to deliberately tweak colors out of their normal tonal ranges, using negative inversions, substitutions, and other manipulations to transform the palette of a picture. But his overall approach isn’t to amplify an image to the point of eye-catching provocation, or to play visual games with brashly “wrong” colors. Instead, Rothman seems to have started with an emotional range that he wanted to elicit and then worked his way back to interventions that supported those desired moods. Defining his zone of intention is a bit tricky – it starts with humility in the face of natural grandeur, adds in reverence, respect, and a warm sense of remembrance, and then falls off toward feelings of anxiety, dread, frustration, fragility, and drifting strangeness. Especially when he settles into a classic landscape view of one kind or another and then viscerally upends our visual assumptions with his most imaginative tonal impressions, his visions of the future of the Sierras become not only understatedly apocalyptic but also serenely wistful, longing for a past that he actually knows and now misses and fearful of the possibilities he can readily extrapolate or imagine.

Rothman’s tonal inversions come in many flavors, from small, targeted, partial color twists to transformations of the entire edge-to-edge palette of full images. In reshaping these scenes, he’s subtly asking us whether we’ll be able to discern the pivot points as he pushes us further and further from reality. At first, his manipulations are limited to some purpling of rocks or plants, a tinting of the sky toward orange or copper, and even some deliberately misaligned layering that leads to tiny visual artifacts like weirdly blurred edges or branches inexplicably tossed in the sky. Soon, these colorations engulf more and more of the compositions, with skies pushed to seething wildfire oranges and views of falling rivers and paths through forests becoming magically unbalanced, as in fairy tales. As the pages flip, ancient trees spout bristles of purple, mountainsides shine unnaturally, and an eerie silence seems to wait for whatever punch of unreality might come next.

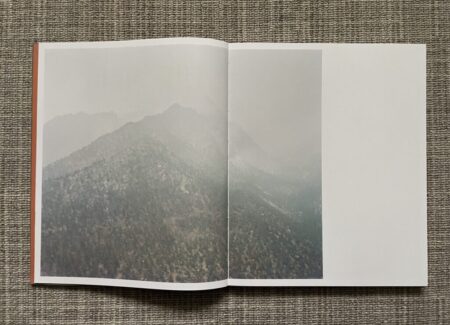

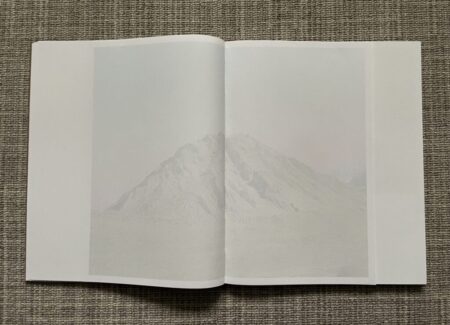

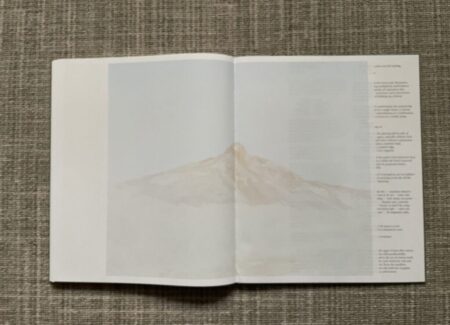

A handful of Rothman’s images have been printed on smaller, extra thin white paper, and interleaved from time to time in the larger sequence of The Sierra. It might be safe to describe these photographs as almost entirely washed to whiteness, the smoke or haze (as well as Rothman’s digital veiling) creating a ghostly mist through which we can only barely discern the mountain peaks, rocky hillsides, and scraggly valleys. There is a delicacy to this presentation that makes the land feel particularly threatened and breakable, the once proud landscape fading away like a faint memory. While these images are indeed lovely in their softly muted tonalities, I also found them quietly sad – I wanted to squint my eyes to pull them into sharper focus, to see them better.

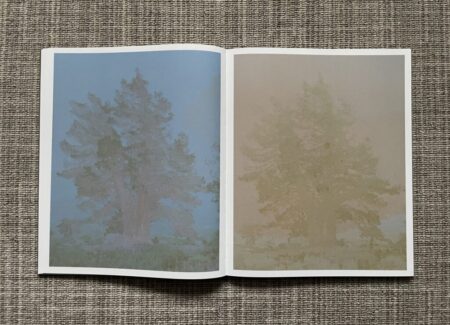

Rothman takes a slightly different approach when he isolates a single specimen from the surrounding landscape, in essence making a portrait of a massive tree, a tall spindly pine, a charred trunk, or a particularly gnarled patch of thicket or undergrowth. In these works, he uses more expressive tinting, still washing the images out, but now with mists of blue, green, purple, yellow, almond, dusty pink, peach, and burnished bronze. The reversals and warps of color in these pictures again feel like fleeting memories, or perhaps unimagined futures where the skies darken in unexpected ways. The trees themselves are as majestic and impressive as ever, particularly in their towering verticality, but their surroundings (and they themselves) have been transformed, bathing them in a choking haze of smoky color, almost like copper plate etchings. A sense of foreboding permeates these pictures too, the solitary trees vainly fighting to survive in some new world they couldn’t possibly have imagined.

In this way, The Sierra is a photobook filled with unresolved landscape contradictions. Almost every picture has a duality of interpretation, where oscillations back and forth between past, present, and future lead to consistent instability. Of course, this is likely some version of the future we face as the climate continues to change, so perhaps these photographs are in their own way artistically prophetic. I for one felt the ache of loss in The Sierra, watching as these familiar American landscape forms melted into elusively ungraspable approximations. The whole project feels on the disheartening cusp of fading away, offering us a last fleeting glimpse of a world we once recognized.

Collector’s POV: Aaron Rothman is represented by Rick Wester Fine Art in New York (here). Rothman’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail likely remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.