JTF (just the facts): A total of 9 color photographs, framed in dark walnut and unmatted, and hung against the six white walls in the divided gallery space. All of the works are digital c-prints, made between 2006 and 2014. Each of the prints is sized 48×60, and is available in an edition of 7 or 8. A monograph of this body of work was recently published by Dewi Lewis ($58, here); it has 144 pages, 64 color plates, and an introductory essay by the artist. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: The English photographer Michael Collins is a reformed art critic who for the last 15 years has devoted himself almost exclusively to photographing with an 8 x 10 camera. Although in his choice of equipment and his even-tempered, coolly descriptive gaze, he can be linked to the Düsseldorf school, Collins prefers to trace his roots further back, to the tradition of mostly anonymous “record picture” British photographers who documented large-scale civil engineering projects in the 19th century.

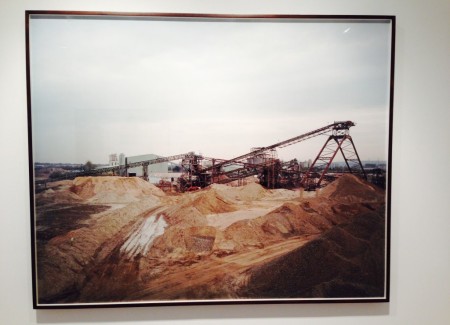

Eight of the nine pictures in the show are English landscapes that once hummed with economic activity and that are now quiet in the aftermath of a historical downturn or the inevitable erosions of time.

The title is a reminder that factories, rather than divorced from the land, have always been married to it. The compositions reiterate this point. Buildings are framed so that we can see how architects planned them to take advantage of natural forces. These structures would never have existed in these places were it not for the waterways that delivered the fuel to heat kilns or drive turbines. The pulverized rock used to make concrete arrived on barges as well as railroad cars.

In his four views of the Stewartby Brickwork in Bedforshire, for example, Collins stands at a distance from this defunct business, once the busiest brickyard in the world. In three of the photographs, he foregrounds the red clay that has seeped into the dirty soil; in a fourth the camera peers over the abandoned factory complex—like a medieval castle with its central courtyard—so that we can see far off the strip of river where products were shipped to and from other counties in England and beyond.

For the most part, even when focused on massive buildings, Collins doesn’t heighten their monumentality. In his series on the Battersea Power Station in South West London—the largest brick building in Europe and now threatened by demolition—he aims his camera straight-forward, emphasizing broken windows and a general air of dilapidation. (He could just as easily have set up his tripod at a lower angle and tried to overwhelm us with the inhuman scale.)

The Burleigh Pottery in Stoke-on-Trent is captured in an image of a mantelpiece crowded with examples of its wares and crowned with a framed portrait of the company’s founder. The antiquated display and tiled fireplace represent a sensibility that has not kept up with the times, and one that Collins seems partial to, as was Walker Evans whenever he came upon places or things that were once modern and are now stranded in the past.

The book is a fuller representation of the artist’s mindset than the exhibition where the oversized prints clash with the self-effacing aims of the work. As you flip through the pages, the program that links images together is more apparent, with the eroding forces of nature becoming the dominant subject in the photographs, ending in a series of marshy landscapes where direct signs of human striving have vanished into the sand.

Collins doesn’t seem to mind slow destruction. A realist in his desire to suggest the eventual fate of all earthly things, he is also the sort of curmudgeon who would likely prefer the Battersea Power Station to stay empty rather than see it repurposed into a contemporary art emporium like the Tate Modern, which packs crowds into the former Bankside Power Station.

His photographs offer no political comment. Stewartby was shuttered in 2008 after it couldn’t meet the government’s sulfur dioxide emission standards. Whether Collins approves of this development or what he thinks about industrial pollutants, we can’t tell. As a photographic observer, he doesn’t see that as part of his job.

Nor did the 19th century landscape photographers, employed to document the factual wonders of the industrial revolution. Their collectors were the businesses that commissioned them or western governments boasting of their leadership—as capitalist innovators or colonial powers—among nations. Photography helped them to prove their cultural superiority.

Evidence that Collins has not entirely renounced his former profession can be sampled in his excellent essay for the book. While providing a capsule history of landscape painting and photography, he recalls his initial thrill of peering at the details of a scene through a ground-glass and spells out his artistic credo.

“The matter of fact nature of photography is its eloquence,” he writes. “Its creativity comes not from an a priori imagining, but a patient observation, and from that close reading, the photograph exposes an unlimited visual dimension…. Photography can show you the things you couldn’t make up. The photographic truth isn’t stranger than fiction, it’s more fascinating. “

Neither a typographer like the Bechers nor a melodramatist like Andrew Moore, Collins is a sober Romantic as he stands in front of England’s industrial ruins. His fossil record of capitalist dinosaurs feels deeply personal without being self-important. This is his third show at Borden and his best. He deserves a wide audience.

Collector’s POV: Each of the prints in this show is priced at $10000. Collins’ work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.

Informative review – and excellent gallery shots.

I think the ground level brickyard landscapes are his best works, I really like them and am more than a teeny bit jealous, they’re really great for all sorts of reasons, some elaborated upon here. As for the others, nah, not really.

I read a stock photographer blog a few days ago (David Taylor-Hughes) saying his generic photos of places taken from a high vantage point sell better as they look more professional – which has kind of made me question the whole elevated viewpoint thing at the moment as being rather calculated after all. As for Battersea power station it should be pulled down if only to stop art photographers taking pictures inside it.

Two stars, yes, but Paul Graham will go absolutely mental.