JTF (just the facts): Published in 2014 by Princeton Architectural Press (here). Hardcover (15 x 7 ½ inches), 156 pages, with 91 duotones, 4 double-page panoramas, and 2 triple-page gatefolds of 7 x 17 photographs made between 1984 and 2011. Includes an essay and notes by Geremie Barmé. $50 (Spread shots below.)

Comments/Context: Lois Conner has been working on this book for almost 30 years even if for half of that time she didn’t know that’s what she was doing. When she began to photograph in the Chinese capital, in the mid-‘80s, Beijing was still called Peking in Western newspapers. The economic reforms that would transform the country had only a tenuous hold.

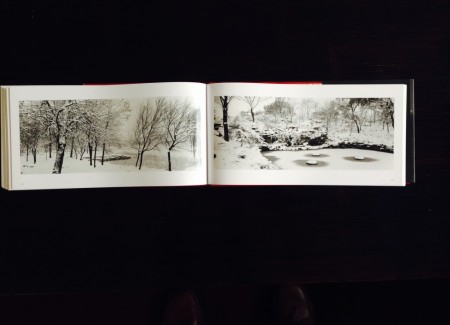

The pictures she made then with her panoramic camera were discovered by wandering and marked by atmosphere: a wintry scene on Hortensia Island in Beihai Park where the roof of a pagoda is ridged with snow; homes and shops of the poor on a corner of the Ring Road; a carved stone lotus flower fallen on the ground, broken off ornament from the European Palaces in the Garden of Perfect Brightness; a deserted alley-way of patched walls and dusty bric-a-brac near Peking University.

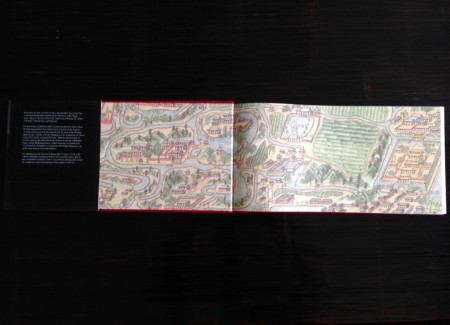

It was Geremie Barmé, the eminent Australian sinologist, who suggested in 1998 the two might collaborate on a project about the Garden of Perfect Brightness, a Qing dynasty ruin. In the years after, they expanded their dual efforts to other imperial monuments and the rapidly mutating social landscape. Most of the pictures in the book were taken since their decision to team up.

Barmé sees the capital as tumultuous space that has undergone multiple cycles of destruction and rebirth. The photographs reiterate that theme, portraying the country as a permanent construction site, whether it’s the concrete and ibar rooftops, busy with workers, at the I.M. Pei-designed Bank of China or the tranquil half-rebuilt remains of a bridge inside an emperor’s garden.

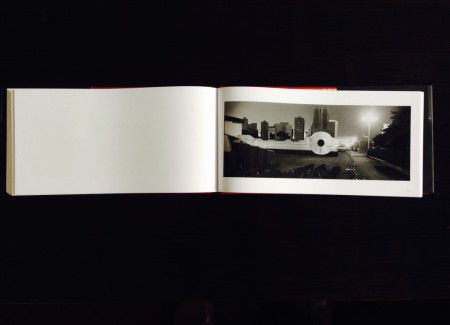

Unlike the 2007 book Phantom Shanghai, Greg Girard’s photographic cri de coeur about small-scale architecture and a lower middle-class way of Chinese life being flattened by economic progress and government fiat, Conner’s views of Beijing in transition are presented with equanimity. The various time frames clash. High-rise Beijing looms over a formidable Ming-dynasty brick wall at night. (The soft detail achieved in what must have been a long exposure is particularly fine.) A fantasy hotel with an Egyptian theme and a drive-in theater packed with cars are followed by an overhead panorama of a far less prosperous China where tarpaulin roofs are held down by bricks and power lines crowd the air.

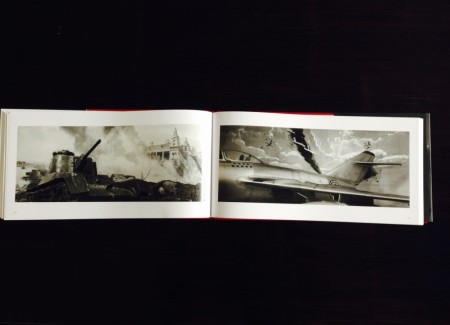

The Maoist period has left behind its own relics, as seen here in a double-page spread of dioramas at the Chinese People’s Revolutionary Military Museum. Conner doesn’t need to camp it up. The empty tank and the jet fighters in front of the painted explosions are funny and pathetic by themselves. The next image—I detect Barme’s cynical humor here—is a display case of passenger jetliners at Boeing’s headquarters: China has turned the page and we do, too.

Neither a photojournalist nor an illustrator of historic sites, Conner is a self-directed artist and famously independent. She has never had trouble making beautiful pictures out of unpromising situations. Her ability to position her camera just so and bend jarring pictorial materials to her own ends is demonstrated throughout. In a ground-level view of the CCTV building under construction, the funky rumpled metal sheets that keep out the public seem to be almost from another century when seen against the canted angles and smooth glass planes of Rem Koolhaas’s sci-fi design.

This collaborative, and more systematic approach to picture-making, has allowed her to work incrementally as never before. According to Barmé, he would suggest a place he would like to write about; she would then go for a site visit and assess whether she “could make meaningful work.” Her sinuous images need no justification, but they gain in descriptive strength by contributing to a larger view of a country where she has traveled and photographed for 30 years. The back-and-forth exchange between her and Barme’s informative text—essential for parsing the often arcane historical symbolism behind what we’re seeing—have resulted in her most substantial book to date.

Collector’s POV: Lois Conner is represented in New York by Gitterman Gallery (here); a review of her recent show there can be found here. Conner’s work has little secondary market history, so gallery retail remains the best option for those collectors interested in following up.