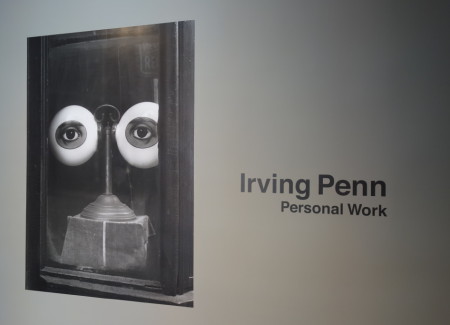

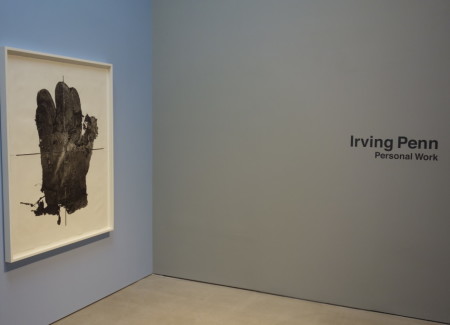

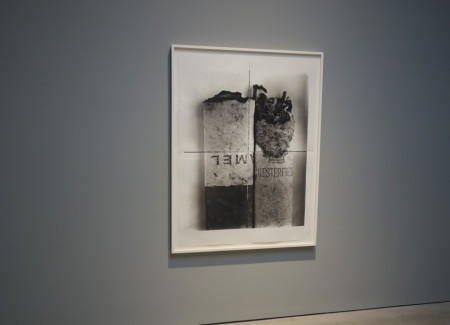

JTF (just the facts): A total of 50 black-and-white photographs, matted and framed, hung on gray or celadon walls, in the five rooms of the gallery. Seventeen of the prints are platinum palladium; the remaining 33 are gelatin silver. (Of the latter, 22 are vintage.) The images were made between 1939 and 2000. Three of the palladium platinum images—Mud Glove, Cigarette No. 37 and Cigarette No. 69—are four-panel composites that together measure approx. 60 x 45 inches. All are signed, titled, and annotated; most are dated as well. Editions vary from as few as 9 to as many as 69. (Installation shots below.)

Comments/Context: Pumping up the rhetoric for the upcoming Irving Penn retrospective, scheduled to open at the Met in 2017, Pace/MacGill declares in its press release that he was “probably the most prolific and respected photographer of the 20th century.” (If so, then Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, and Lee Friedlander, here are your hats.)

Such hyperbole might be more defensible if this selection from some 60 years of work backed up the claim with a feast of astonishments. But the surprises are few and the decision to feature only black-and-white prints makes everything on the walls look more austere and grim than perhaps necessary. (Can it be that Penn never photographed in color except at the behest of others?)

Unlike last year’s substantial and vivacious On Assignment, these examples of his so-called Personal Work aren’t surrounded by hand-written notebooks or tear sheets or other documents that allow you to see how methodically he went about creating his images and cataloging his process. Without scholarly footnotes to deepen the context of their creation or meaning, the pictures in the new show are left naked, and many of them—the cigarette butts, big female nudes, Camel pack, fallen pitcher and broken plate—suffer from being so familiar.

The decision by the gallery to split his career in two, between the photographs Penn made for magazines and clients, and those he commissioned from himself, seems arbitrary as well as illuminating. For more than 30 years, Penn enjoyed the support of Alexander Liberman at Condé Nast, so much so that pretty much any picture he wanted to make was guaranteed space in the Christmas issue of Vogue and thus could be called “personal work.”

On the one hand, while it’s technically true that the group portraits of the Hell’s Angels in San Francisco were the result of a job for Look magazine, while his group portraits of the Dancers Workshop of San Francisco were done without commercial sponsorship, it seems irrational to segregate them into different shows. Both sessions date from 1967 and are related to the point of being indistinguishable in style.

On the other hand, the distinction says something about Penn’s career, even if accidentally. He seems to have been an artist who let himself go most completely when in service to others. Forced to solve a problem that would satisfy a client and his own Olympian standards of perfection, he felt liberated to invent—to corner celebrities in an uncongenial space or to build a Modernist house out of unboxed frozen fruits and vegetables. With no one to answer to but himself, his tendency toward a hermetic Puritanism sometimes got the better of him.

Personal Work is not without satisfactions. (How could it not be, with rooms of Penn prints?)

Each of the animal skulls here, a group of four from a collection he photographed at the Prague Museum in 1986, has a fierce, individual architecture that he highlights through shrewd formal choices. Penn has placed his camera at a slight side angle to the massive structure of a brown bear’s bony head so that both of the dark empty holes in the cranium—including the one for its huge sensitive nose—seem to be the animal’s eyes. A bear has two sets of teeth—the meat-tearing incisors vertically fixed the front, and the smaller set of molars, horizontally laid out for grinding toward the back of the mouth. By centering the composition on the latter, he gives the animal a ferocious lopsided smile. No monster maker in Hollywood could have sculpted a form as alien and frightening as this top predator.

There are some rarities here, including a group of three self-portraits from 1993 in which his 75 year-old bald head is distorted. In each picture he wears a different expressions—sad-sack resignation; histrionic despair; sober reflection—as if he were trying on masks. These are exhibited in a quiet corner next to Woman Turning Over (1995), an almost Cubistic portrait of a women’s torqued movements. Made with an experimental camera of his own design, it’s the most startling image in the show.

It’s uplifting to be reminded what a first-rate street photographer he was as a young man, and how much he owed to Walker Evans in the late ‘30s and early ‘40s. Even if some of these images (Optician’s Shop Window, in particular) have been reproduced often, they reveal that when Penn began to make close-ups in the mid-‘70s of material fished out of the gutter, he was walking on familiar ground.

His platinum prints of giant cigarette butts, done around the same time, exhibit the same austere sensibility. The sensation they caused at his retrospective at the Marlborough Gallery in 1977 is hard to imagine, much less recreate. The six examples here from the series not only don’t look oversized compared to average photographic prints today, they no longer seem coarse or undignified.

And that may be the most revealing insight to be gained from this cross-section of his personal work. As justly renowned as he was for his immersion in couture and commerce, and his ascetic revision of their beauty, I don’t think that any photographer has ever been so enamored with dirt—in all of its granularity and exquisite shades and metaphorical depths—as Penn.

Collector’s POV: Prices range from $20000 for the four gelatin-silver prints from the Dancers Workshop of San Francisco to $400000 for the four-panel palladium-platinum prints (two are for sale; one is a loan). The average price for the other works in the show is between $60000 and $70000. Penn’s prints are ubiquitous in the secondary markets, with dozens of examples available every season. Prices have ranged from $8000 to $460000 in recent years, with prices steadily increasing since the artist’s death in 2009.